THE STORY OF LITTLE NELL

I. IN THE OLD CURIOSITY SHOP

It was a queer home for a child—this place where Little Nell lived with her grandfather. He was a dealer in all sorts of curious old things: suits of mail which stood like ghosts in armor here and there; fantastic carved tables and chairs; rusty weapons of various kinds; distorted figures in china and wood and iron. And, amid it all, the oldest thing in the shop seemed to be the little old man with the long gray hair.

The only bit of youth was Nell herself; and yet she had a strange intermingling of dignity and responsibility, in spite of her small figure and childish ways. Her fourteen years of life had left her undecided between childhood and girlhood. She had not begun to grow up; and yet she was an orphan, accustomed to doing everything for herself.

Her grandfather tried in his way to take care of her, for he loved her dearly. But between the tending of his shop and the mysterious journeys which he made night after night, the child was often sent upon strange errands or left alone in the old house. And at all times it was she who took care of him. But the old man did not see that this lonely life was putting lines of sorrow into her face. To him she was still the child of yesterday, care-free and happy.

She had been happy once. She had gone singing through the dim rooms, and moving with gay step among their dusty treasures, making them older by her young life, and sterner and more grim by her cheerful presence. But now the chambers were cold and gloomy, and when she left her own little room to while away the tedious hours, and sat in one of them, she was still and motionless as their inanimate occupants, and had no heart to startle the echoes—hoarse from their long silence—with her voice.

In one of these rooms was a window looking into the street, where the child sat, many and many a long evening, and often far into the night, alone and thoughtful. None are so anxious as those who watch and wait; and at these times mournful fancies came flocking on her mind in crowds.

She knew instinctively that her grandfather was hiding something from her. What it was she could not guess; but these regular journeys at night, while she watched and waited, left him only the more fretful and careworn. He seemed to have a constant fever for something; yet all he would say was that he would some day leave her a fortune. Meanwhile he had fallen into the clutches of Quilp a terrible dwarf, who had lent him money from time to time, until the entire contents of the shop were mortgaged. So it is not strange that Little Nell should have mournful thoughts.

When the night had worn away, the child would close the window and even smile, with the first dawn of light, at her night-time fears. Then after praying earnestly for her grandfather and the restoring of their former happy days, she would unlatch the door for him and fall into a troubled sleep.

One night the old man said that he would not leave home. The child’s face lit up at the news, but became grave again when she saw how worried he looked.

“You took my note safely to Mr. Quilp, you say?” he asked fretfully. “What did he tell you, Nell?”

“Exactly what I told you, dear grandfather, indeed.”

“True,” said the old man, faintly. “Yes. But tell me again, Nell. My head fails me. What was it that he told you? Nothing more than that he would see me to-morrow or next day? That was in the note.”

“Nothing more,” said the child. “Shall I go to him again to-morrow, dear grandfather? Very early? I will be there and back before breakfast.”

The old man shook his head and, sighing mournfully, drew her towards him.

“‘T would be no use, my dear, no earthly use. But if he deserts me, Nell, at this moment—if he deserts me now, when I should, with his assistance, be recompensed for all the time and money I have lost and all the agony of mind I have undergone, which makes me what you see, I am ruined and worse,—far worse than that—I have ruined you, for whom I ventured all. If we are beggars—!”

“What if we are?” said the child, boldly. “Let us be beggars and be happy.”

“Beggars—and happy!” said the old man. “Poor child!”

“Dear grandfather,” cried the girl with an energy which shone in her flushed face, trembling voice, and impassioned gesture, “I am not a child in that I think, but even if I am, oh, hear me pray that we may beg, or work in open roads or fields, to earn a scanty living, rather than live as we do now.”

“Nelly!” said the old man.

“Yes, yes, rather than live as we do now,” the child repeated more earnestly than before. “If you are sorrowful, let me know why and be sorrowful too; if you waste away and are paler and weaker every day, let me be your nurse and try to comfort you. If you are poor, let us be poor together; but let me be with you, do let me be with you; do not let me see such change and not know why, or I shall break my heart.”

The child’s voice was lost in sobs, as she clasped her arms about the old man’s neck; nor did she weep alone.

These were not words for other ears, nor was it a scene for other eyes. And yet other ears and eyes were there and greedily taking in all that passed, and moreover they were the ears and eyes of no less a person than Mr. Daniel Quilp, who, having entered unseen when the child first placed herself at the old man’s side, stood looking on with his accustomed grin. Standing, however, being tiresome, and the dwarf being one of that kind of persons who usually make themselves at home, he soon cast his eyes upon a chair, into which he skipped with uncommon agility, and perching himself on the back with his feet upon the seat, was thus enabled to look on and listen with greater comfort to himself, besides gratifying at the same time that taste for doing something fantastic and monkey-like, which on all occasions had strong possession of him. Here, then, he sat, one leg cocked carelessly over the other, his chin resting on the palm of his hand, his head turned a little on one side, and his ugly features twisted into a complacent grimace. And in this position the old man, happening in course of time to look that way, chanced to see him.

The child uttered a suppressed shriek on beholding this figure; in their first surprise both she and the old man, not knowing what to say, and half doubting its reality, looked shrinkingly at it. Not at all disconcerted by this reception, Daniel Quilp preserved the same attitude, merely nodding twice or thrice with great condescension. At length, the old man pronounced his name and inquired how he came there.

“Through the door,” said Quilp, pointing over his shoulder with his thumb. “I’m not quite small enough to get through keyholes. I wish I was. I want to have some talk with you, particularly, and in private—with nobody present, neighbor. Good-bye, little Nelly.”

Nell looked at the old man, who nodded to her to retire, and kissed her cheek.

The dwarf said never a word, but watched his companion as he paced restlessly up and down the room, and presently returned to his seat. Here he remained, with his head bowed upon his breast for some time, and then suddenly raising it, said,

“Once, and once for all, have you brought me any money?”

“No!” returned Quilp.

“Then,” said the old man, clenching his hands desperately and looking upward, “the child and I are lost!”

“Neighbor,” said Quilp, glancing sternly at him, and beating his hand twice or thrice upon the table to attract his wandering attention, “let me be plain with you, and play a fairer game than when you held all the cards, and I saw but the backs and nothing more. You have no secret from me, now.”

The old man looked up, trembling.

“You are surprised,” said Quilp. “Well, perhaps that’s natural. You have no secret from me now, I say; no, not one. For now I know that all those sums of money, that all those loans, advances, and supplies that you have had from me, have found their way to—shall I say the word?”

“Aye!” replied the old man, “say it if you will.”

“To the gaming-table,” rejoined Quilp, “your nightly haunt. This was the precious scheme to make your fortune, was it; this was the secret certain source of wealth in which I was to have sunk my money (if I had been the fool you took me for); this was your inexhaustible mine of gold, your El Dorado, eh?”

“Yes,” cried the old man, turning upon him with gleaming eyes, “it was. It is. It will be, till I die.”

“That I should have been blinded,” said Quilp, looking contemptuously at him, “by a mere shallow gambler!”

“I am no gambler,” cried the old man, fiercely. “I call Heaven to witness that I never played for gain of mine, or love of play. It was all for her—for my little Nelly! I had sworn to leave her rich!”

“When did you first begin this mad career?” asked Quilp, his taunting inclination subdued, for a moment, by the old man’s grief and wildness.

“When did I first begin?” he rejoined, passing his hand across his brow. “When was it, that I first began? When should it be, but when I began to think how little I had saved, how long a time it took to save at all, how short a time I might have, at my age, to live, and how she would be left to the rough mercies of the world with barely enough to keep her from the sorrows that wait on poverty; then it was that I began to think about it.”

“Humph! the old story,” said the dwarf. “You lost what money you had laid by, first, and then came to me. While I thought you were making your fortune (as you said you were) you were making yourself a beggar, eh? Dear me! And so it comes to pass that I hold every security you could scrape together, and a bill of sale upon the—upon the stock and property. But did you never win?”

“Never!” groaned the old man. “Never won back my loss!”

“I thought,” sneered the dwarf, “that if a man played long enough he was sure to win at last, or, at the worst, not to come off a loser.”

“And so he is!” cried the old man, “so he is; I have felt that from the first, I have always known it, I’ve seen it, I never felt it half so strongly as I feel it now. Quilp, I have dreamed, three nights, of winning the same large sum. I never could dream that dream before, though I have often tried. Do not desert me, now I have this chance! I have no resource but you,—give me some help, let me try this one last hope.”

The dwarf shrugged his shoulders and shook his head.

“Nay, Quilp, good Quilp!” gasped the old man, extending his hands in entreaty; “let me try just this once more. I tell you it is not for me—it is for her! Oh, I cannot die and leave her in poverty!”

“I couldn’t do it, really,” said Quilp, with unusual politeness. And grinning and making a low bow he passed out of the door.

The dwarf was, for once, as good as his word. He not only refused to lend any more money, but he at once began to make plans for closing the shop. The old man was so broken-hearted that he fell ill of a raging fever, and for days was delirious. Little Nell, his only nurse, gradually learned the truth about her grandfather’s evening pursuit—the gaming-table—and it added all the more to her sorrow.

At last when he was well enough to go about again, the impatient dwarf would not be put off any longer in regard to the sale. An early day was fixed for it, and the old dealer no longer offered any objections. Instead, he sat quietly, dully in his chair, looking at a tiny patch of green through his window.

To one who had been tossing on a restless bed so long, even these few green leaves and this tranquil light, although it languished among chimneys and house-tops, were pleasant things. They suggested quiet places afar off, and rest and peace.

The child thought, more than once, that he was moved and had forborne to speak. But now he shed tears—tears that it lightened her aching heart to see—and making as though he would fall upon his knees, he besought her to forgive him.

“Forgive you—what?” said Nell, interposing to prevent his purpose. “Oh, grandfather, what should I forgive?”

“All that is past, all that has come upon you, Nell,” returned the old man.

“Do not talk so,” said the child. “Pray do not. Let us speak of something else.”

“Yes, yes, we will,” he rejoined. “And it shall be of what we talked of long ago—many months—months is it, or weeks, or days? which is it, Nell?”

“I do not understand you,” said the child.

“You said, let us be beggars and happy in the open fields,” he answered. “Oh, let us go away—anywhere!”

“Yes, let us go,” said Nell, earnestly; “there will we find happiness and peace.”

And so it was arranged. On the night before the public auction they were to steal forth quietly, out into the wide world.

The old man had slept for some hours soundly in his bed, while she was busily engaged in preparing for their flight. There were a few articles of clothing for herself to carry, and a few for him; old garments, such as became their fallen fortunes, laid out to wear; and a staff to support his feeble steps, put ready for his use. But this was not all her task, for now she must visit the old rooms for the last time.

And how different the parting with them was from any she had expected, and most of all from that which she had oftenest pictured to herself! How could she ever have thought of bidding them farewell in triumph, lonely and sad though her days had been! She sat down at the window where she had spent so many evenings—-darker far, than this—and every thought of hope or cheerfulness that had occurred to her in that place came vividly upon her mind, and blotted out all its dull and mournful associations in an instant.

Her own little room, too, where she had so often knelt down and prayed at night—prayed for the time which she hoped was dawning now—the little room where she had slept so peacefully, and dreamed such pleasant dreams—it was hard to leave it without one kind look or grateful tear.

But at last she was ready to go, and her grandfather was awakened. Just as the first rays of dawn were seen they stole forth noiselessly, hand in hand. They dared not awaken Quilp, who was sleeping that night in the shop to guard his prospective wealth. Out in the middle of the street they paused.

“Which way?” said the child.

The old man looked irresolutely and helplessly, first at her, then to the right and left, then at her again, and shook his head. It was plain that she was thenceforth his guide and leader. The child felt it, but had no doubts or misgiving, and putting her hand in his led him gently away.

II. OUT IN THE WIDE WORLD

It was a bright morning in June when Nell and her grandfather set forth upon their travels. Out of the city they walked briskly, for the desire to leave their old life—to elude pursuit—lay strong upon them. Nell had provided a simple lunch for that day’s needs; and at night they stopped foot-sore and weary at a hospitable farmhouse.

Late in the next day they chanced to pass a country church. Among the tombstones, at one side, they saw two men who were seated upon the grass, so busily at work as not to notice the newcomers.

It was not difficult to guess that they were of a class of travelling showmen who went from town to town showing Punch and his antics, for perched upon a tombstone was a figure of that hero himself, his nose and chin as hooked and his face as beaming as usual.

Scattered upon the ground were the other members of the play, in various stages of repair; while the two showmen were engaged with glue, hammer, and tacks, in putting their proper parts more strongly together.

The showmen raised their eyes when the old man and his young companion were close upon them, and pausing in their work, returned their looks of curiosity. One of them, the actual exhibitor, no doubt, was a little merry-faced man with a twinkling eye and a red nose, who seemed to have unconsciously imbibed something of his hero’s character. The other—that was he who took the money—had rather a careful and cautious look, which was perhaps inseparable from his occupation also.

The merry man was the first to greet the strangers with a nod; and following the old man’s eyes, he observed that perhaps that was the first time he had ever seen a Punch off the stage.

“Why do you come here to do this?” asked the old man, after answering their greeting.

“Why, you see,” rejoined the little man, “we’re putting up for to-night at the public-house yonder, and it wouldn’t do to let ’em see the present company undergoing repair.”

“No!” cried the old man, making signs to Nell to listen, “why not, eh? why not?”

“Because it would destroy all the delusion, and take away all the interest, wouldn’t it?” replied the little man. “Would you care a ha’penny for the Lord Chancellor if you know’d him in private and without his wig?—certainly not.”

“Good!” said the old man, venturing to touch one of the puppets, and drawing away his hand with a shrill laugh. “Are you going to show ’em to-night? are you?”

“That is the intention, governor,” replied the other. “Look here,” he continued, turning to his partner, “here’s all this Judy’s clothes falling to pieces again. Much good you do at sewing things!”

Seeing that they were at a loss, the child said timidly:

“I have a needle, sir, in my basket, and thread too. Will you let me try to mend it for you? I think I can do it neater than you could.”

The showman had nothing to urge against a proposal so seasonable. Nelly, kneeling down beside the box, was soon busily engaged in her task, and accomplishing it to a miracle.

While she was thus engaged, the merry little man looked at her with an interest which did not appear to be diminished when he glanced at her helpless companion. When she had finished her work he thanked her, and inquired whither they were travelling.

“N—no farther to-night, I think,” said the child, looking towards her grandfather.

“If you’re wanting a place to stop at,” the man remarked, “I should advise you to take up at the same house with us. That’s it—the long, low, white house there. It’s very cheap. Come along.”

The tavern was kept by a fat old landlord and landlady who made no objection to receiving their new guests, but praised Nelly’s beauty and were at once prepossessed in her behalf. There was no other company in the kitchen but the two showmen, and the child felt very thankful that they had fallen upon such good quarters. The landlady was very much astonished to learn that they had come all the way from London, and appeared to have no little curiosity touching their farther destination. But Nell could give her no very clear replies.

That evening the wayfarers enjoyed the Punch show, though poor Nell was so tired that she went to sleep early in the performance.

The next morning she met the showmen at breakfast.

“And where are you going to-day?” asked the little man with the red nose.

“Indeed, I hardly know. We have not decided,” replied the child.

“We’re going to the races,” said the little man. “If that’s your way and you’d like to have us for company, let us travel together.”

“We’ll go with you, and gladly,” interposed Nell’s grandfather, eagerly; for he had been as pleased as a child with the performance of Punch.

Nell was a trifle alarmed over the prospect of a crowded race-course; but this seemed their best chance to press forward, so she accepted the invitation thankfully.

For several days they travelled together, and despite the wearisome way the child found much novelty and interest in the wandering life. But presently she became uneasy in the changed attitude of the two showmen. From being ordinarily kind, they now seemed to watch Nell and her grandfather so closely as not to suffer them out of their sight.

The showmen had, in fact, got it into their heads that the two wayfarers were not common people, but runaways for whom a reward must even now be posted in London. And so they resolved to deliver them over to the proper authorities at the first opportunity and claim the reward.

Now, although Nell and her grandfather had a perfect right to go where they pleased, and there was no reward offered, they were at all times fearful of being pursued by that terrible Quilp. So Nell determined to flee from these two watchful men at the earliest moment.

The chance of escape offered during one of the busy days at the race-course. While the two men were busy showing off Punch to the delighted crowd, she took her grandfather by the hand and hurriedly slipped away.

At first they pressed forward regardless of whither their steps led them, and from time to time casting fearful glances behind them to see if they were being pursued. But as they drew farther away they gained more confidence. Weariness also forced them to slacken their pace. When they had come into the middle of a little woodland they rested a short time; then encountered a path which led to the opposite side. Taking their way along it for a short distance they came to a lane, so shaded by the trees on either hand that they met together overhead, and arched the narrow way. A broken finger-post announced that this led to a village three miles off; and thither they resolved to bend their steps.

The miles appeared so long that they sometimes thought they must have missed their road. But at last, to their great joy, it led downward in a steep descent, with overhanging banks over which the footpaths led; and the clustered houses of the village peeped from the woody hollow below.

It was a very small place. The men and boys were playing at cricket on the green; and as the other folks were looking on, they wandered up and down, uncertain where to seek a humble lodging. There was but one man in the little garden before his cottage, and him they were timid of approaching, for he was the schoolmaster, and had “School” written up over his window in black letters on a white board. He was a pale, simple-looking man, and sat among his flowers and beehives, smoking his pipe, in the little porch before his door.

“Speak to him, dear,” the old man whispered.

“I am almost afraid to disturb him,” said the child, timidly. “He does not seem to see us. Perhaps if we wait a little, he may look this way.”

But as nobody else appeared and it would soon be dark, Nell at length ventured to draw near, leading her grandfather by the hand. The slight noise they made in raising the latch of the wicket-gate caught his attention. He looked at them kindly but seemed disappointed too, and slightly shook his head.

Nell dropped a courtesy, and told him they were poor travellers who sought a shelter for the night which they would gladly pay for, so far as their means allowed. The schoolmaster looked earnestly at her as she spoke, laid aside his pipe, and rose up directly.

“If you could direct us anywhere, sir,” said the child, “we should take it very kindly.”

“You have been walking a long way,” said the schoolmaster.

“A long way, sir,” the child replied.

“You’re a young traveller, my child,” he said, laying his hand gently on her head. “Your grandchild, friend?”

“Aye, sir,” cried the old man, “and the stay and comfort of my life.”

“Come in,” said the schoolmaster.

Without farther preface he conducted them into his little school-room, which was parlor and kitchen likewise, and told them they were welcome to remain under his roof till morning. Before they had done thanking him, he spread a coarse white cloth upon the table, with knives and platters; and bringing out some bread and cold meat, besought them to eat.

They did so gladly, and the schoolmaster showed them, soon after, to some plain but neat sleeping chambers up close under the thatched roof. Here they slept the sound sleep of the very weary, and awoke refreshed and light-hearted the following day.

But the schoolmaster, while kind and courteous, was sad and quiet. He gave his small school a half-holiday that day, and Nell learned that it was because of the illness of a favorite pupil—a boy about her own age.

“If your journey is not a long one,” he added to the travellers, “you’re very welcome to pass another night here. I should really be glad if you would do so, as I am very lonely to-day.”

They accepted and thanked him with grateful hearts. Nell busied herself tidying up the rooms and trying in many little ways to add to the master’s comfort. And that evening, when his pupil died, Nell’s grief was almost as deep in its sympathy as the master’s own.

She bade him a reluctant farewell the next morning. School had already begun, but he rose from his desk and walked with them to the gate.

It was with a trembling and reluctant hand that the child held out to him the money which a lady had given her at the races for some flowers; faltering in her thanks as she thought how small the sum was, and blushing as she offered it. But he bade her put it up, and stooping to kiss her cheek, turned back into his house.

They had not gone half-a-dozen paces when he was at the door again; the old man retraced his steps to shake hands, and the child did the same.

“Good fortune and happiness go with you!” said the poor schoolmaster. “I am quite a solitary man now. If you ever pass this way again, you’ll not forget the little village school.”

“We shall never forget it, sir,” rejoined Nell; “nor ever forget to be grateful to you for your kindness to us.”

“I have heard such words from the lips of children very often,” said the schoolmaster, shaking his head and smiling thoughtfully, “but they were soon forgotten. I had attached one young friend to me, the better friend for being young—but that’s over—God bless you!”

They bade him farewell very many times and turned away, walking slowly and often looking back, until they could see him no more. At length they had left the village far behind, and even lost sight of the smoke among the trees. They trudged onward now at a quicker pace, resolving to keep the main road, and go wherever it might lead them.

But main roads stretch a long, long way. With the exception of two or three inconsiderable clusters of cottages which they passed without stopping, and one lonely roadside public-house where they had some bread and cheese, this highway had led them to nothing—late in the afternoon—and still lengthened out, far in the distance, the same dull, tedious, winding course that they had been pursuing all day. As they had no resource, however, but to go forward, they still kept on, though at a much slower pace, being very weary and fatigued.

Finally, just at dusk, they came upon a curious little house upon wheels—a travelling show somewhat more pretentious than the Punch performance they had run away from. This little house was mounted upon a cart, with white dimity curtains at the windows and shutters of green set in panels of bright red. Altogether it was a smart little contrivance. Grazing in front of it were two comfortable-looking horses; while at its open door sat a stout lady—evidently the proprietor—sipping tea.

This lady, Mrs. Jarley by name, had seen Nell and her grandfather at the races, so hailed them and asked about the success of the Punch show. She was greatly astonished to learn that they had nothing to do with it, and were wandering about without any object in view.

Her own performance was more “classic,” as she expressed it. It was a Waxwork exhibition; and as she looked at Nell’s attractive face she was seized with an idea. This bright little girl was just the sort of assistant she had been needing. So she invited them to stop and have some tea with her. They did so; and when Mrs. Jarley presently unfolded her plan—which was to engage Nell to exhibit the wax figures and describe them in a set speech—Nell was delighted to accept the offer, especially since it involved no separation from her grandfather, who could dust the figures and do other light tasks.

It was really not a very hard position for Nell. At the first town where the Waxworks were to be shown, Nell was given a private view and instructed in her new duties. The figures were displayed on a raised platform some two feet from the floor, running round the room and parted from the rude public by a crimson rope breast high. They represented celebrated characters, singly and in groups, clad in glittering dresses of various climes and times, and standing more or less unsteadily upon their legs, with their eyes very wide open, and their nostrils very much inflated, and the muscles of their legs and arms very strongly developed, and all their countenances expressing great surprise. All the gentlemen were very pigeon-breasted and very blue about the beards, and all the ladies were miraculous figures; and all the ladies and all the gentlemen were looking with extraordinary earnestness at nothing at all.

Nell was taught a little speech about each one of them, and so apt was she that one rehearsal rendered her able to take the willow wand, which Mrs. Jarley had formerly wielded, and tell the interesting history of this very select Waxwork show to the audiences which presently began to come.

Mrs. Jarley herself was delighted with her venture. She saw at once that Nell would be a strong drawing card. And in order that the child might remain contented she made her and her grandfather as comfortable as possible, besides paying them a fair salary.

So the wanderers now rode in the van from town to town, and lived almost happily. Nell carefully saved all their money, and watched over her feeble grandfather with the tenderness of a little mother. She had one scare in almost meeting face to face with Quilp, the dwarf, but he had not recognized her.

Quilp, indeed, was a perpetual nightmare to the child, who was constantly haunted by a vision of his ugly face and stunted figure. She slept, for their better security, in the room where the waxwork figures were, and she never retired to this place at night but she tortured herself—she could not help it—with imagining a resemblance, in some one or other of their death-like faces, to the dwarf, and this fancy would sometimes so gain upon her that she would almost believe he had removed the figure and stood within the clothes.

But presently a deeper and more real concern came to her. Her grandfather had never alluded to their former life, nor to his passion for gambling. He did not see the card-tables out in the country; and that was the reason why she had been so eager to wander, even without a roof over their heads. But now, as the Waxworks exhibited only in the towns, temptation came again to the poor, weak old man. He saw some men playing cards in a tavern, and instantly his slumbering passion was aroused. He would play again and win a great fortune—for Nell!

He began to play, and, of course, with the old result. He was but a tool in the hands of the sharpers, and presently he had exhausted all the slender hoard which Nell had so carefully made. She watched his actions with a bursting heart, but was powerless to stop him or keep the money out of his grasp. At last the villains who had led him on—not satisfied with their small winnings from him—urged him to get the money belonging to the Waxwork show, saying that when he won he could pay it all back.

Nell had followed her grandfather upon this visit to the gamblers, and overheard their plot. She knew there was but one thing to do, to save her grandfather. They must flee out into the world again at once. That night she roused him from his sleep, and told him they must go away.

“What does this mean?” he cried.

“I have had dreadful dreams,” said the child. “If we stay here another night something awful will happen. Come!”

The old man looked at her as if she were a spirit, and trembled in every joint.

“Must we go to-night?” he asked.

“Yes, to-night,” she replied. “To-morrow night will be too late. The dream will have come again. Nothing but flight can save us. Up!”

The old man rose obediently and made ready to follow. She had already packed their scanty belongings. She gave him his wallet and staff, and secretly, in the night, they fled away.

The wanderings of the next few days seemed like a nightmare to them. Nell had brought only a few pennies in her pockets and these went for a scant supply of bread and cheese. Two days and a night they rode on an open canal-boat in company with some rough but not unkind men. It was easier than walking, but the rain descended in torrents and drenched them to the skin.

Finally the boat drew up to a wharf in an ugly manufacturing town, and the travellers were cast adrift as lonely and helpless as though they had just awakened from a sleep of a thousand years. They had not one friend, nor the least idea where to turn for shelter. But a rough stoker at one of the furnaces told them that they might pass the night in front of his fire. It was nothing but a bed of ashes, yet they were warm and the heat dried out the poor travellers’ drenched garments.

The child felt stiff and weak in every joint the next morning, but the furnace-tender told them that it was two days’ journey to the open country and sweet, pure fields, and she felt that they must press forward at any cost. So they started forth, slowly and wearily, for their journey and privations had almost exhausted them, but still with brave hearts. Through long rows of red brick houses that looked exactly alike they wended their way, asking for bread to eat only when obliged to, and meeting little else but scowls from the dirty factory workers.

Finally, to their great joy, the open country began again to appear; and with fresh courage in their hearts they continued to press on.

They were dragging themselves along through the last street, and the child felt that the time was close at hand when her enfeebled powers would bear no more; when there appeared before them, going in the same direction as themselves, a traveller on foot, who, with a portmanteau strapped to his back, leaned upon a stout stick as he walked, and read from a book which he held in his other hand.

It was not an easy matter to come up with him, and beseech his aid, for he walked fast, and was a little distance in advance. At length he stopped to look more attentively at some passage in his book. Animated with a ray of hope, the child shot on before her grandfather, and going close to the stranger without rousing him by the sound of her footsteps, began, in a few faint words, to implore his help.

He turned his head. The child clapped her hands together, uttered a wild shriek, and fell senseless at his feet.

III. AT THE END OF THE JOURNEY

It was the poor schoolmaster. Scarcely less moved and surprised by the sight of the child than she had been on recognizing him, he stood, for a moment, without even the presence of mind to raise her from the ground.

But quickly recovering his self-possession, he threw down his stick and book, and dropping on one knee beside her, endeavored by such simple means as occurred to him to restore her to herself; while her grandfather, standing idly by, wrung his hands, and implored her with many endearing expressions to speak to him, were it only a word.

“She is quite exhausted,” said the schoolmaster, glancing upward into his face. “You have taxed her powers too far, friend.”

“She is perishing of want,” rejoined the old man. “I never thought how weak and ill she was till now.”

Casting a look upon him, half reproachful and half compassionate, the schoolmaster took the child in his arms, and, bidding the old man gather up her little basket and follow him directly, bore her away at his utmost speed.

There was a small inn within sight, to which, it would seem, he had been directing his steps when so unexpectedly overtaken. Towards this place he hurried with his unconscious burden, and rushing into the kitchen deposited it on a chair before the fire.

A doctor was hastily called in and restoratives were applied; after which Nell was given what she most needed, some warm broth and toast, and was put to bed.

The schoolmaster asked anxiously after her health the next morning, and was greatly relieved to find that she was much better, though still so weak that it would require a day’s careful nursing before she could proceed upon her journey. That evening he was allowed to see her, and was greatly touched by the sight of her pale, pinched face. But she held out both hands to him.

“It makes me unhappy even in the midst of all this kindness,” said the child, “to think that we should be a burden upon you. How can I ever thank you? If I had not met you so far from home, I must have died, and poor grandfather would have no one to take care of him.”

“We’ll not talk about dying,” said the schoolmaster, “and as to burdens, I have made my fortune since you slept at my cottage.”

“Indeed!” cried the child, joyfully.

“Oh, yes,” returned her friend. “I have been appointed clerk and schoolmaster to a village a long way from here—and a long way from the old one as you may suppose—at five-and-thirty pounds[#] a year. Five-and-thirty pounds!”

[#] About $175.

“I am very glad,” said the child—”so very, very glad.”

“I am on my way there now,” resumed the schoolmaster. “They allowed me the stagecoach hire—outside stage-coach hire all the way. Bless you, they grudge me nothing. But as the time at which I am expected there left me ample leisure, I determined to walk instead. How glad I am to think I did so!”

“How glad should we be!”

“Yes, yes,” said the schoolmaster, moving restlessly in his chair, “certainly, that’s very true. But you—where are you going, where are you coming from, what have you been doing since you left me, what had you been doing before? Now, tell me—do tell me. I know very little of the world, and perhaps you are better fitted to advise me in its affairs than I am qualified to give advice to you; but I am very sincere, and I have a reason (you have not forgotten it) for loving you. I have felt since that time as if my love for him who died had been transferred to you.”

Nell was moved in her turn by this allusion to the favorite pupil who had died, and by the plain, frank kindness of the good schoolmaster. She told him all—that they had no friend or relative—that she had fled with the old man to save him from all the miseries he dreaded—that she was flying now to save him from himself—and that she sought an asylum in some quiet place, where the temptation before which he fell would never enter, and her late sorrows and distresses could have no place.

The schoolmaster heard her with astonishment. “This child!” he thought; “she is one of the heroines and saints of earth!”

Then he told her of a great idea which had occurred to him. They were all three to travel together to the village where his new school was located, and he made no doubt he could find them some simple and congenial employment.

The child joyfully accepted this; and the journey was made very comfortably in a stage which went that way. Stowed among the softer bundles and packages she thought this to be a drowsy, luxurious way of going, indeed.

At last they came upon a quiet, restful-looking hamlet clustered in a valley among some stately trees.

“See—here’s the church!” cried the delighted schoolmaster, in a low voice; “and that old building close beside it is the schoolhouse, I’ll be sworn. Five-and-thirty pounds a year in this beautiful place!”

They admired everything—the old gray porch, the green churchyard, the ancient tower, the very weathercock; the brown thatched roofs of cottage, barn, and homestead, peeping from among the trees; the stream that rippled by the distant watermill; the blue Welsh mountains far away. It was for such a spot the child had wearied in the dense, dark, miserable haunts of labor. Upon her bed of ashes, and amidst the squalid horrors through which they had forced their way, visions of such scenes—beautiful indeed, but not more beautiful than this sweet reality—had been always present to her mind. They had seemed to melt into a dim and airy distance, as the prospect of ever beholding them again grew fainter; but, as they receded, she had loved and panted for them more.

“I must leave you somewhere for a few minutes,” said the schoolmaster, at length breaking the silence into which they had fallen in their gladness. “I have a letter to present, and inquiries to make, you know. Where shall I take you? To the little inn yonder?”

“Let us wait here,” rejoined Nell. “The gate is open. We will sit in the church porch till you come back.”

“A good place, too,” said the schoolmaster, leading the way towards it. “Be sure that I come back with good news, and am not long gone.”

So the happy schoolmaster put on a brand-new pair of gloves which he had carried in a little parcel in his pocket all the way, and hurried off, full of ardor and excitement.

The child watched him from the porch until the intervening foliage hid him from her view, and then stepped softly out into the old churchyard—so solemn and quiet that every rustle of her dress upon the fallen leaves, which strewed the path and made her footsteps noiseless, seemed an invasion of its silence. It was an aged, ghostly place; the church had been built hundreds of years before; yet from this first glimpse the child loved it and felt that in some strange way she was a part of its crumbling walls and grass-grown churchyard.

After a time the schoolmaster reappeared, hurrying towards them and swinging a bunch of keys.

“You see those two houses?” he asked, pointing, quite out of breath. “Well, one of them is mine.”

Without saying any more, or giving the child time to reply, the schoolmaster took her hand, and, his honest face quite radiant with exultation, led her to the place of which he spoke.

They stopped before its low, arched door. After trying several of the keys in vain, the schoolmaster found one to fit the huge lock, which turned back, creaking, and admitted them into the house.

It was a very old house, and, like the church, falling into decay, yet still handsome with high vaulted ceilings and queer carvings. It was not quite destitute of furniture. A few strange chairs, whose arms and legs looked as though they had dwindled away with age; a table, the very spectre of its race; a great old chest that had once held records in the church, with other quaintly fashioned domestic necessaries, and store of firewood for the winter, were scattered around, and gave evident tokens of its occupation as a dwelling-place, at no very distant time.

The child looked around her, with that solemn feeling with which we contemplate the work of ages that have become but drops of water in the great ocean of eternity. The old man had followed them, but they were all three hushed for a space, and drew their breath softly, as if they feared to break the silence, even by so slight a sound.

“It is a very beautiful place!” said the child, in a low voice.

“I almost feared you thought otherwise,” returned the schoolmaster. “You shivered when we first came in, as if you felt it cold or gloomy.”

“It was not that,” said Nell, glancing round with a slight shudder. “Indeed, I cannot tell you what it was, but when I saw the outside, from the church porch, the same feeling came over me. It is its being so old and gray, perhaps.”

“A peaceful place to live in, don’t you think so?” said her friend.

“Oh, yes,” rejoined the child, clasping her hands earnestly. “A quiet, happy place—a place to live and learn to die in!”

“A place to live, and learn to live, and gather health of mind and body in,” said the schoolmaster; “for this old house is yours.”

“Ours!” cried the child.

“Aye,” returned the schoolmaster, gaily, “for many a merry year to come, I hope. I shall be a close neighbor—only next door—but this house is yours.”

Having now disburdened himself of his great surprise, the schoolmaster sat down, and drawing Nell to his side, told her how he had learned that the ancient tenement had been occupied for a very long time by an old person, who kept the keys of the church, opened and closed it for the services, and showed it to strangers; how she had died not many weeks ago, and nobody had yet been found to fill the office; how, learning all this in an interview with the sexton, he had hurried to the clergyman and obtained the vacant post for Nell and her grandfather.

“There’s a small allowance of money,” said the schoolmaster. “It is not much, but still enough to live upon in this retired spot. By clubbing our funds together, we shall do bravely; no fear of that.”

“Heaven bless and prosper you!” sobbed the child.

“Amen, my dear,” returned her friend, cheerfully; “and all of us, as it will, and has, in leading us through sorrow and trouble to this tranquil life. But we must look at my house now. Come!”

They repaired to the other tenement; tried the rusty keys as before; at length found the right one; and opened the worm-eaten door. It led into a chamber, vaulted and old, like that from which they had come, but not so spacious, and having only one other little room attached. It was not difficult to divine that the other house was of right the schoolmaster’s, and that he had chosen for himself the least commodious, in his care and regard for them. Like the adjoining habitation, it held such old articles of furniture as were absolutely necessary, and had its stack of firewood.

To make these dwellings as habitable and full of comfort as they could, was now their pleasant care. In a short time, each had its cheerful fire glowing and crackling on the hearth, and reddening the pale old walls with a hale and healthy blush. Nell, busily plying her needle, repaired the tattered window-hangings, drew together the rents that time had worn in the threadbare scraps of carpet, and made them whole and decent. The schoolmaster swept and smoothed the ground before the door, trimmed the long grass, trained the ivy and creeping plants, which hung their drooping heads in melancholy neglect; and gave to the outer walls a cheery air of home. The old man, sometimes by his side and sometimes with the child, lent his aid to both, went here and there on little patient services, and was happy. Neighbors, too, as they came from work, proffered their help; or sent their children with such small presents or loans as the strangers needed most. So it was not many days before they were quite cosy; and Nell felt again, in that strange way which had come over her at the church, that she had always been a part of the place.

And how she loved her work from the very first! Hour after hour she would spend in the old church, dusting off its pews or casements with reverent fingers, or more often, sitting quietly before some tablet or inscription looking at it or beyond it, with a dreamy light in her eyes.

Her grandfather noted her attitude anxiously. He saw that she grew more listless and frail, day by day, and he sought constantly—poor old man!—to lighten her few tasks. But it was not these which wearied her; it was merely the burden of all things earthly.

Every person in the village soon grew to love this frail, spiritual-looking child; but from the first she seemed a being apart from them. They were constantly showing her kindness, or pausing at the church gate to speak with her; but as they went their way, a sad smile or shake of the head told only too plainly of their fears. She was like some rare, delicate flower which, they knew, could not endure the frost of winter.

The good schoolmaster gently chided her for spending so much of her time in the church and among the graves, instead of out in the light and sunshine. But she only smiled and said she loved to tend the graves and keep them neat, for she could not bear to think that any lying there should be forgotten, or that she herself might be forgotten some day.

“There is nothing good that is forgotten,” he replied kindly. “There is not an angel added to the host of Heaven but does its blessed work on earth in those that loved it here.”

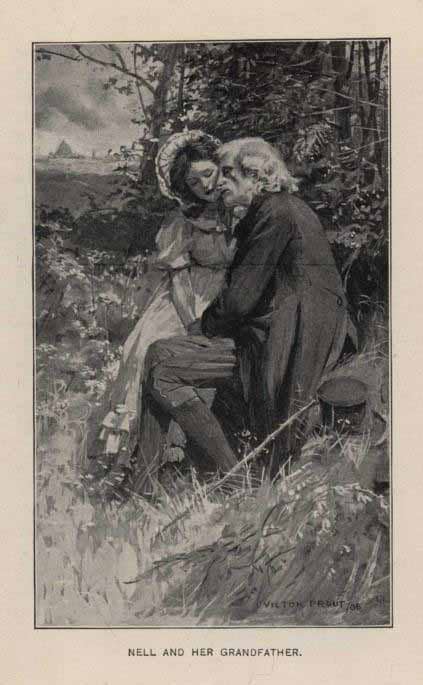

As the cold days of autumn and winter drew on, the child spent more and more time within doors, on a couch before the fire. The slightest task wearied her now, and her grandfather kept watch night and day to save her needless steps. He could scarcely bear her out of his sight; and often would creep to the side of her couch during the night, listening to her breathing or stroking her slender fingers softly. And if by chance she awoke and smiled on him, he would creep back to his own bed comforted.

But one chill morning in midwinter, when the snow lay thickly on the ground, it seemed to him that she slept more quietly than usual. The schoolmaster, coming in, found him crouched over a fire, muttering softly to himself, and wondering why she slumbered so long. The two went softly into her chamber, and then the schoolmaster knew why she was so quiet.

For she was dead. Dear, gentle, patient, noble Nell was dead. No sleep so beautiful and calm, so free from trace of pain, so fair to look upon. She seemed a creature fresh from the hand of God, and waiting the breath of life; not one who had lived and suffered death.

The old man held one languid arm in his, and had the small hand tight folded to his breast, for warmth. It was the hand she had stretched out to him with her last smile—the hand that had led him on, through all their wanderings. Ever and anon he pressed it to his lips, then hugged it to his breast again, murmuring that it was warmer now; and, as he said it, he looked in agony to the schoolmaster, as if imploring him to help her.

She was dead, and past all help, or need of it. The ancient rooms she had seemed to fill with life, even while her own was waning fast; the garden she had tended; the eyes she had gladdened; the noiseless haunts of many a thoughtful hour; the paths she had trodden as it were but yesterday—could know her nevermore.

“It is not,” said the schoolmaster, as he bent down to kiss her on the cheek, and gave his tears free vent, “it is not on earth that Heaven’s justice ends. Think what earth is, compared with the world to which her young spirit has winged its early flight, and say, if one deliberate wish expressed in solemn terms above this bed could call her back to life, which of us would utter it!”

The whole village, young and old, came to the churchyard when they laid her to rest—save only the old man. He could not realize that she was dead, and he had gone to pick winter berries to decorate her couch.

When he returned and could not find her, they were obliged to tell him the truth—that her body had been put away in the cold earth—and then his grief and distress were pitiful to see. He seemed at once to lose all power of thought or action, save as they concerned her alone.

Day by day he sought for her about the house or in the garden, calling her name wildly. At other times he sat before the fire staring dully, and did not seem to hear when they spoke to him.

At length, they found, one day, that he had risen early, and, with his knapsack on his back, his staff in hand, her own straw hat, and little basket full of such things as she had been used to carry, was gone. As they were making ready to pursue him far and wide, a frightened schoolboy came who had seen him, but a moment before, sitting in the church—upon her grave, he said.

They hastened there, and going softly to the door, espied him in the attitude of one who waited patiently. They did not disturb him then, but kept a watch upon him all that day. When it grew quite dark, he rose and returned home, and went to bed, murmuring to himself, “She will come to-morrow!”

Upon the morrow he was there again from sunrise until night; and still at night he laid him down to rest, and murmured, “She will come to-morrow!”

And thenceforth, every day, and all day long, he waited at her grave for her. How many pictures of new journeys over pleasant country, of resting-places under the free broad sky, of rambles in the fields and woods, and paths not often trodden; how many tones of that one well-remembered voice; how many glimpses of the form, the fluttering dress, the hair that waved so gaily in the wind; how many visions of what had been, and what he hoped was yet to be—rose up before him, in the old, dull, silent church! He never told them what he thought, or where he went. He would sit with them at night, pondering with a secret satisfaction, they could see, upon the flight that he and she would take before night came again; and still they would hear him whisper in his prayers, “Lord! Let her come to-morrow!”

The last time was on a genial day in spring. He did not return at the usual hour, and they went to seek him. He was lying dead upon the stone.

They laid him by the side of her whom he had loved so well; and, in the church where they had often prayed and mused and lingered hand in hand, the child and the old man slept together.