PART II.

CHAPTER I.

VOYAGES ROUND THE WORLD, AND POLAR EXPEDITIONS.

The Russian fur trade—Kruzenstern appointed to the command of an expedition—Noukha-Hiva—Nangasaki—Reconnaisance of the coast of Japan—Yezo—The Ainos—Saghalien—Return to Europe—Otto von Kotzebue—Stay at Easter Island—Penrhyn—The Radak Archipelago—Return to Russia—Changes at Otaheite and the Sandwich Islands—Beechey's Voyage—Easter Island—Pitcairn and the mutineers of the Bounty—The Paumoto Islands—Otaheite and the Sandwich Islands—The Bonin Islands—Lütke—The Quebradas of Valparaiso—Holy week in Chili—New Archangel—The Kaloches—Ounalashka—The Caroline Archipelago—The canoes of the Caroline Islanders—Guam, a desert island—Beauty and happy situation of the Bonin Islands—The Tchouktchees: their manners and their conjurors—Return to Russia.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Russians for the first time took part in voyages round the world, Until that time their explorations had been almost entirely confined to Asia, and their only mariners of note were Behring, Tchirikoff, Spangberg, Laxman, Krenitzin, and Saryscheff. The last-named took an important part in the voyage of the Englishman Billings, a voyage by the way which was far from achieving all that might have been fairly expected from the ten years it occupied and the vast sums it cost.

Adam John von Kruzenstern was the first Russian to whom is due the honour of having made a voyage round the world under government auspices and with a scientific purpose.

Born in 1770, Kruzenstern entered the English navy in 1793. After six years’ training in the stern school which then numbered amongst its leaders the most skilful sailors of the world, he returned to his native land with a profound knowledge of his profession, and with his ideas of the part Russia might play in Eastern Asia very considerably widened.

During a stay of two years at Canton, in 1798 and 1799, Kruzenstern had been witness of the extraordinary results achieved by some English fur traders, who brought their merchandise from the northwest coasts of Russian America. This trade had not come into existence until after Cook’s third voyage, and the English had already realized immense sums, at the cost of the Russians, who had hitherto sent their furs to the Chinese markets overland.

In 1785, however, a Russian named Chelikoff founded a fur-trading colony on Kodiak Island, at about an equal distance from Kamtchatka and the Aleutian Islands, which rapidly became a flourishing community. The Russian government now recognized the resources of districts it had hitherto considered barren, and reinforcements, provisions, and stores were sent to Kamtchatka via Siberia.

Kruzenstern quickly realized how inadequate to the new state of things was help such as this, the ignorance of the pilots and the errors in the maps leading to the loss of several vessels every year, not to speak of the injury to trade involved in a two years’ voyage for the transport of furs, first to Okhotsk, and thence to Kiakhta.

As the best plans are always the simplest they are sure to be the last to be thought of, and Kruzenstern was the first to point out the imperative necessity of going direct by sea from the Aleutian Islands to Canton, the most frequented market.

On his return to Russia, Kruzenstern tried to win over to his views Count Kuscheleff, the Minister of Marine, but the answer he received destroyed all hope. Not until the accession of Alexander I., when Admiral Mordinoff became head of the naval department, did he receive any encouragement.

Acting on Count Romanoff’s advice, the Russian Emperor soon commissioned Kruzenstern to carry out the plan he had himself proposed; and on the 7th August, 1802, he was appointed to the command of two vessels for the exploration of the north-west coast of America.

Although the leader of the expedition was named, the officers and seamen were still to be selected, and the vessels to be manned were not to be had in either the Russian empire or at Hamburg. In London alone were Lisianskoï, afterwards second in command to Kruzenstern, and the builder Kasoumoff, able to obtain two vessels at all suitable to the service in which they were to be employed. These two vessels received the names of the Nadiejeda and the Neva.

In the meantime, the Russian government decided to avail itself of this opportunity to send M. de Besanoff to Japan as ambassador, with a numerous suite, and magnificent presents for the sovereign of the country.

On the 4th August, 1803, the two vessels, completely equipped, and carrying 134 persons, left the roadstead of Cronstadt. Flying visits were paid to Copenhagen and Falmouth, with a view to replacing some of the salt provisions bought at Hamburg, and to caulk the Nadiejeda, the seams of which had started in a violent storm encountered in the North Sea.

After a short stay at the Canary Islands, Kruzenstern hunted in vain, as La Pérouse had done before him, for the Island of Ascension, as to the existence of which opinion had been divided for some three hundred years. He then rounded Cape Frio, the position of which he was unable exactly to determine although he was most anxious to do so, the accounts of earlier travellers and the maps hitherto laid down varying from 23° 6′ to 22° 34′. A reconnaissance of the coast of Brazil was succeeded by a sail through the passage between the islands of Gal and Alvaredo, unjustly characterized as dangerous by La Pérouse, and on the 21st December, 1803, St. Catherine was reached.

The necessity for replacing the main and mizzen masts of the Neva detained Kruzenstern for five weeks on this island, where he was most cordially received by the Portuguese authorities.

On the 4th February, the two vessels were able to resume their voyage, prepared to face all the dangers of the South Sea, and to double Cape Horn, that bugbear of all navigators. As far as Staten Island the weather was uniformly fine, but beyond it the explorers had to contend with extremely violent gales, storms of hail and snow, dense fogs, huge waves, and a swell in which the vessels laboured heavily. On the 24th March, the ships lost sight of each other in a dense fog a little above the western entrance to the Straits of Magellan. They did not meet again until both reached Noukha-Hiva.

Kruzenstern having given up all idea of touching at Easter Island, now made for the Marquesas, or Mendoza Archipelago, and determined the position of Fatongou and Udhugu Islands, called Washington by the American Captain Ingraham, who discovered them in 1791, a few weeks before Captain Marchand, who named them Revolution Islands. Kruzenstern also saw Hiva-Hoa, the Dominica of Mendaña, and at Noukha-Hiva met an Englishman named Roberts, and a Frenchman named Cabritt, whose knowledge of the language was of great service to him.

The incidents of the stay in the Marquesas Archipelago are of little interest, they were much the same as those related in Cook’s Voyages. The total, but at the same time utterly unconscious immodesty of the women, the extensive agricultural knowledge of the natives, and their greed of iron instruments, are commented upon in both narratives.

Nothing is noticed in the later which is not to be found in the earlier narrative, if we except some remarks on the existence of numerous societies of which the king or his relations, priests, or celebrated warriors, are the chiefs, and the aim of which is the providing of the people with food in times of scarcity. In our opinion these societies resemble the clans of Scotland or the Indian tribes of America. Kruzenstern, however, does not agree with us, as the following quotation will show.

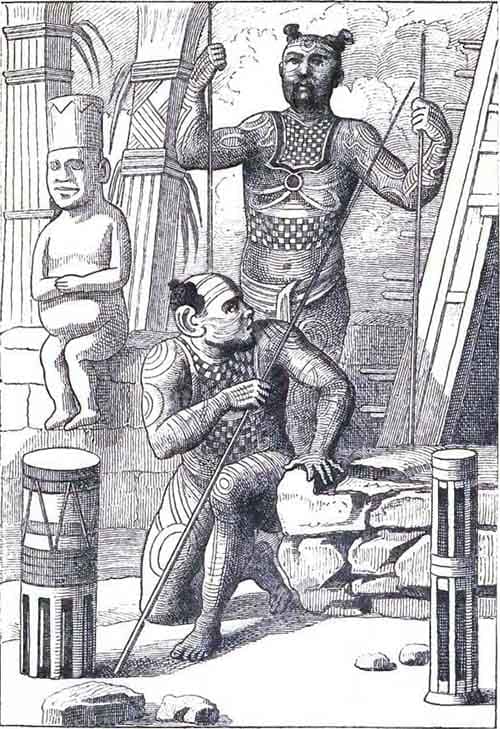

“The members of these clubs are distinguished by different tattooed marks upon their bodies; those of the king’s club, consisting of twenty-six members, have a square one on their breasts about six inches long and four wide, and to this company Roberts belonged. The companions of the Frenchman, Joseph Cabritt, were marked with a tattooed eye, &c. Roberts assured me that he never would have entered this association, had he not been driven to it by extreme hunger. There was an apparent want of consistency in this dislike, as the members of these companies are not only relieved from all care as to their subsistence, but, even by his own account, the admittance into them is a distinction that many seek to obtain. I am therefore inclined to believe that it must be attended with the loss of some part of liberty.”

A reconnaissance of the neighbourhood of Anna Maria led to the discovery of Port Tchitchagoff, which, though the entrance is difficult, is so shut in by land that its waters are unruffled by the most violent storm.

At the time of Kruzenstern’s visit to Noukha-Hiva, cannibalism was still largely practised, but the traveller had no tangible proof of the prevalence of the custom. In fact Kruzenstern was very affably received by the king of the cannibals, who appeared to exercise but little authority over his people, a race addicted to the most revolting vices, and our hero owns that but for the intelligent and disinterested testimony of the two Europeans mentioned above he should have carried away a very favourable opinion of the natives.

“In their intercourse with us,” he says, “they always showed the best possible disposition, and in bartering an extraordinary degree of honesty, always delivering their cocoa-nuts before they received the piece of iron that was to be paid for them. At all times they appeared ready to assist in cutting wood and filling water; and the help they afforded us in the performance of these laborious tasks was by no means trifling. Theft, the crime so common to all the islanders of this ocean, we very seldom met with among them; they always appeared cheerful and happy, and the greatest good humour was depicted in their countenances…. The two Europeans whom we found here, and who had both resided with them several years, agreed in their assertions that the natives of Nukahiva were a cruel, intractable people, and, without even the exceptions of the female sex, very much addicted to cannibalism; that the appearance of content and good-humour, with which they had so much deceived us, was not their true character; and that nothing but the fear of punishment and the hopes of reward, deterred them from giving a loose to their savage passions. These Europeans described, as eye-witnesses, the barbarous scenes that are acted, particularly in times of war—the desperate rage with which they fall upon their victims, immediately tear off their head, and sip their blood out of the skull,1 with the most disgusting readiness, completing in this manner their horrible repast. For a long time I would not give credit to these accounts, considering them as exaggerated; but they rest upon the authority of two different persons, who had not only been witnesses for several years to these atrocities, but had also borne a share in them: of two persons who lived in a state of mortal enmity, and took particular pains by their mutual recriminations to obtain with us credit for themselves, but yet on this point never contradicted each other. The very fact of Roberts doing his enemy the justice to allow, that he never devoured his prey, but always exchanged it for hogs, gives the circumstance a great degree of probability, and these reports concur with several appearances we remarked during our stay here, skulls being brought to us every day for sale. Their weapons are invariably adorned with human hair, and human bones are used as ornaments in almost all their household furniture; they also often gave us to understand by pantomimic gestures that human flesh was regarded by them as a delicacy.”

1 "All the skulls which we purchased of them," says Kruzenstern, "had a hole perforated through one end of them for this purpose."

There are grounds for looking upon this account as exaggerated. The truth, probably, lies between the dogmatic assertions of Cook and Forster and those of the two Europeans of Kruzenstern’s time, one of whom at least was not much to be relied upon, as he was a deserter.

And we must remember that we ourselves did not attain to the high state of civilization we now enjoy without climbing up from the bottom of the ladder. In the stone age our manners were probably not superior to those of the natives of Oceania.

We must not, therefore, blame these representatives of humanity for not having risen higher. They have never been a nation. Scattered as their homes are on the wide ocean, and divided as they are into small tribes, without agricultural or mineral resources, without connexions, and with a climate which makes them strangers to want, they could but remain stationary or cultivate none but the most rudimentary arts and industries. Yet in spite of all this, how often have their instruments, their canoes, and their nets, excited the admiration of travellers.

On the 18th May, 1804, the Nadiejeda and the Neva left Noukha-Hiva for the Sandwich Islands, where Kruzenstern had decided to stop and lay in a store of fresh provisions, which he had been unable to do at his last anchorage, where seven pigs were all he could get.

This plan fell through, however. The natives of Owhyhee, or Hawaii, brought but a very few provisions to the vessels lying off their south-west coast, and even these they would only exchange for cloth, which Kruzenstern could not give them. He therefore set sail for Kamtchatka and Japan, leaving the Neva off the island of Karakakoua, where Captain Lisianskoï relied upon being able to revictual.

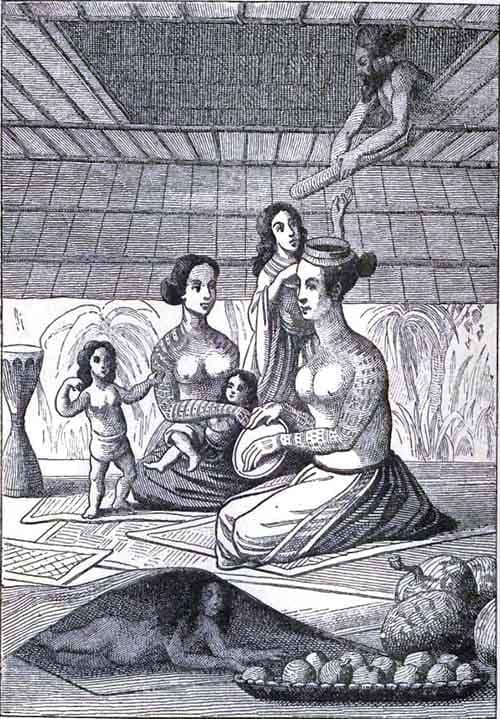

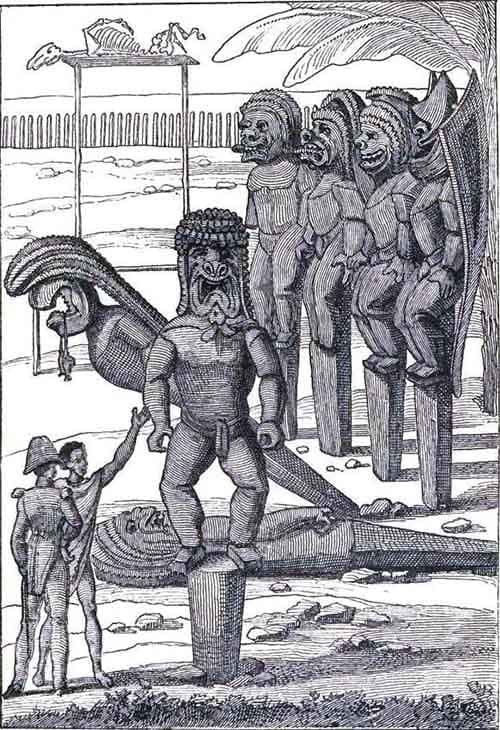

(Fac-simile of early engraving.)

On the 11th July, the Nadiejeda arrived off Petropaulovski, the capital of Kamtchatka, where the crew obtained the rest and fresh provisions they had so well earned. On the 30th August, the Russians put to sea again.

Overtaken by thick fogs and violent storms, Kruzenstern now hunted in vain for some islands marked on a map found on a Spanish gallion captured by Anson, and the existence of which had been alternately accepted and rejected by different cartographers, though they appear in La Billardière’s map of his voyage.

The navigator now passed between the large island of Kiushiu and Tanega-Sima, by way of Van Diemen Strait, till then very inaccurately defined, rectified the position of the Liu-Kiu archipelago, which the English had placed north of the strait, and the French too far south, and sailed down, surveyed and named the coast of the province of Satsuma.

“This part of Satsuma,” says Kruzenstern, “is particularly beautiful: and as we sailed along at a very trifling distance from the land, we had a distinct and perfect view of the various picturesque situations that rapidly succeed each other. The whole country consists of high pointed hills, at one time appearing in the form of pyramids, at others of a globular or conical form, and seeming as it were under the protection of some neighbouring mountain, such as Peak Homer, or another lying north-by-west of it, and even a third farther inland. Liberal as nature has been in the adornment of these parts, the industry of the Japanese seems not a little to have contributed to their beauty; for nothing indeed can equal the extraordinary degree of cultivation everywhere apparent. That all the valleys upon this coast should be most carefully cultivated would not so much have surprised us, as in the countries of Europe, where agriculture is not despised, it is seldom that any piece of land is left neglected; but we here saw not only the mountains even to their summits, but the very tops of the rocks which skirted the edge of the coast, adorned with the most beautiful fields and plantations, forming a striking as well as singular contrast, by the opposition of their dark grey and blue colour to that of the most lively verdure. Another object that excited our astonishment was an alley of high trees, stretching over hill and dale along the coast, as far as the eye could reach, with arbours at certain distances, probably for the weary traveller—for whom these alleys must have been constructed,—to rest himself in, an attention which cannot well be exceeded. These alleys are not uncommon in Japan, for we saw a similar one in the vicinity of Nangasaky, and another in the island of Meac-Sima.”

The Nadiejeda had hardly anchored at the entrance to Nagasaki harbour before Kruzenstern saw several daïmios climb on board, who had come to forbid him to advance further.

Now, although the Russians were aware of the policy of isolation practised by the Japanese government, they had hoped that their reception would have been less forbidding, as they had on board an ambassador from the powerful neighbouring state of Russia. They had relied on enjoying comparative liberty, of which they would have availed themselves to collect information on a country hitherto so little known and about which the only people admitted to it had taken a vow of silence.

They were, however, disappointed in their expectations. Instead of enjoying the same latitude as the Dutch, they were throughout their stay harassed by a perpetual surveillance, as unceasing as it was annoying. In a word, they were little better than prisoners.

Although the ambassador did obtain permission to land with his escort “under arms,” a favour never before accorded to any one, the sailors were not allowed to get out of their boat, or when they did land the restricted place where they were permitted to walk was surrounded by a lofty palisading, and guarded by two companies of soldiers.

It was forbidden to write to Europe by way of Batavia, it was forbidden to talk to the Dutch captains, the ambassador was forbidden to leave his house—the word forbidden may be said to sum up the anything but cordial reception given to their visitors by the Japanese.

Kruzenstern turned his long stay here to account by completely overhauling and repairing his vessel. He had nearly finished this operation when the approach was announced of an envoy from the Emperor, of dignity so exalted that, in the words of the interpreter, “he dared to look at the feet of his Imperial Majesty.”

This personage began by refusing the Czar’s presents, under pretence that if they were accepted the Emperor would have to send back others with an embassy, which would be contrary to the customs of the country; and he then went on to speak of the law against the entry of any vessels into the ports of Japan, and absolutely forbade the Russians to buy anything, adding, however, at the same time, that the materials already supplied for the refitting and revictualling the vessel would be paid for out of the treasury of the Emperor of Japan. He further inquired whether the repairs of the Nadiejeda would soon be finished. Kruzenstern understood what was meant as soon as his visitor began to speak, and hurried on the preparations for his own departure.

Truly he had not much reason to congratulate himself on having waited from October to April for such an answer as this. So little were the chief results hoped for by his government achieved, that no Russian vessel could ever again enter a Japanese port. A short-sighted, jealous policy, resulting in the putting back for half a century the progress of Japan.

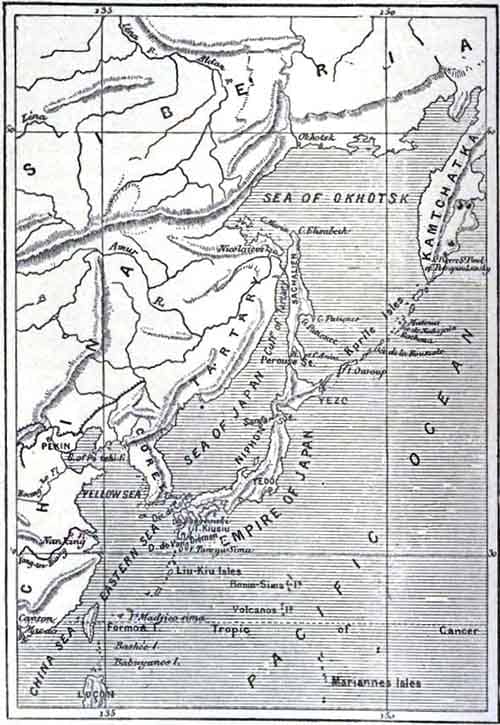

On the 17th April the Nadiejeda weighed anchor, and began a hydrographic survey, which had the best results. La Pérouse had been the only navigator to traverse before Kruzenstern the seas between Japan and the continent. The Russian explorer was therefore anxious to connect his work with that of his predecessor, and to fill up the gaps the latter had been compelled for want of time to leave in his charts of these parts.

“To explore the north-west and south-west coasts of Japan,” says Kruzenstern, “to ascertain the situation of the Straits of Sangar, the width of which in the best charts—Arrowsmith’s ‘South Sea Pilot’ for instance, and the atlas subjoined to La Pérouse’s Voyage—is laid down as more than a hundred miles, while the Japanese merely estimated it to be a Dutch mile; to examine the west coast of Yezo; to find out the island of Karafuto, which in some new charts, compiled after a Japanese one, is placed between Yezo and Sachalin, and the existence of which appeared to me very probable; to explore this new strait and take an accurate plan of the island of Sachalin, from Cape Crillon to the north-west coast, from whence, if a good harbour were to be found there, I could send out my long boat to examine the supposed passage which divides Tartary from Sachalin; and, finally, to attempt a return through a new passage between the Kuriles, north of the Canal de la Boussole; all this came into my plan, and I have had the good fortune to execute part of it.”

Kruzenstern was destined almost entirely to carry out this detailed plan, only the survey of the western coast of Japan and of the Strait of Sangar, with that of the channel closing the Farakaï Strait, could not be accomplished by the Russian navigator, who had, sorely against his will, to leave the completion of this important task to his successors.

Kruzenstern now entered the Corea Channel, and determined the longitude of Tsusima, obtaining a difference of thirty-six minutes from the position assigned to that island by La Pérouse. This difference was subsequently confirmed by Dagelet, who can be fully relied upon.

The Russian explorer noticed, as La Pérouse had done before him, that the deviation of the magnetic needle is but little noticeable in these latitudes.

The position of Sangar Strait, between Yezo and Niphon, being very uncertain, Kruzenstern resolved to determine it. The mouth, situated between Cape Sangar (N. lat. 41° 16′ 30″ and W. long. 219° 46′) and Cape Nadiejeda (N. lat. 41° 25′ 10″, W. long. 219° 50′ 30″), is only nine miles wide; whereas La Pérouse, who had relied, not upon personal observation but upon the map of the Dutchman Vries, speaks of it as ten miles across. Kruzenstern’s was therefore an important rectification.

Kruzenstern did not actually enter this strait. He was anxious to verify the existence of a certain island, Karafonto, Tchoka, or Chicha by name, set down as between Yezo and Saghalien in a map which appeared at St. Petersburg in 1802, and was based on one brought to Russia by the Japanese Koday. He then surveyed a small portion of the coast of Yezo, naming the chief irregularities, and cast anchor near the southernmost promontory of the island, at the entrance to the Straits of La Pérouse.

Here he learnt from the Japanese that Saghalien and Karafonto were one and the same island.

On the 10th May, 1805, Kruzenstern landed at Yezo, and was surprised to find the season but little advanced. The trees were not yet in leaf, the snow still lay thick here and there, and the explorer had supposed that it was only at Archangel that the temperature would be so severe at this time of year. This phenomenon was to be explained later, when more was known as to the direction taken by the polar current, which, issuing from Behring Strait, washes the shores of Kamtchatka, the Kurile Islands, and Yezo.

During his short stay here and at Saghalien, Kruzenstern was able to make some observations on the Ainos, a race which probably occupied the whole of Yezo before the advent of the Japanese, from whom—at least from those who have been influenced by intercourse with China—they differ entirely.

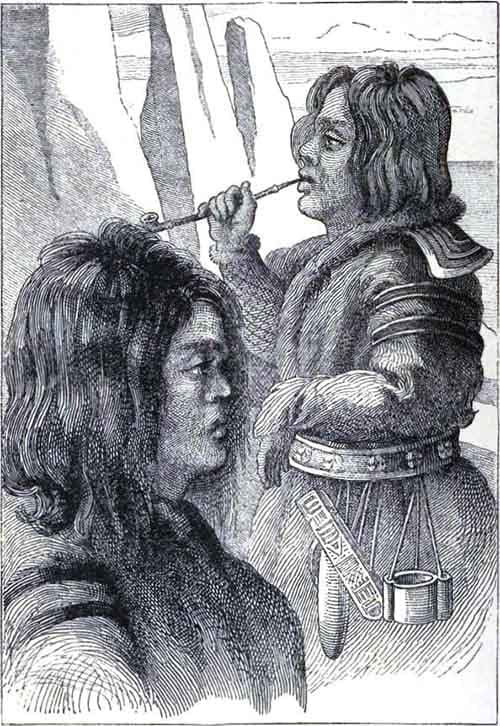

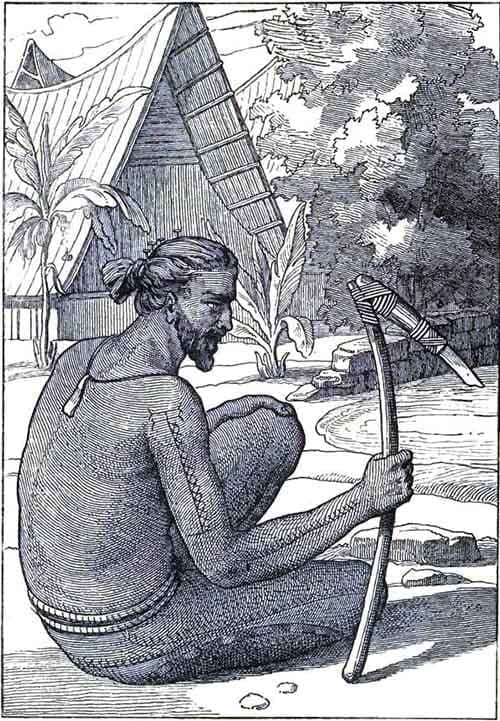

(Fac-simile of early engraving.)

“Their figure,” says Kruzenstern, “dress, appearance, and their language, prove that they are the same people, as those of Saghalien; and the captain of the Castricum, when he missed the Straits of La Pérouse, might imagine, as well in Aniwa as in Alkys, that he was but in one island…. The Ainos are rather below the middle stature, being at the most five feet two or four inches high, of a dark, nearly black complexion, with a thick bushy beard, black rough hair, hanging straight down; and excepting in the beard they have the appearance of the Kamtschadales, only that their countenance is much more regular. The women are sufficiently ugly; their colour, which is equally dark, their coal black hair combed over their faces, blue painted lips, and tattooed hands, added to no remarkable cleanliness in their clothing, do not give them any great pretensions to loveliness…. However, I must do them the justice to say, that they are modest in the highest degree, and in this point form the completest contrast with the women of Nukahiva and of Otaheite…. The characteristic quality of an Aino is goodness of heart, which is expressed in the strongest manner in his countenance; and so far as we were enabled to observe their actions, they fully answered this expression…. The dress of the Ainos consists chiefly of the skins of tame dogs and seals; but I have seen some in a very different attire, which resembled the Parkis of the Kamtschadales, and is, properly speaking a white shirt worn over their other clothes. In Aniwa Bay they were all clad in furs; their boots were made of seal-skins, and in these likewise the women were invariably clothed.”

After passing through the Straits of La Pérouse, Kruzenstern cast anchor in Aniwa Bay, off the island of Saghalien. Here fish was then so plentiful, that two Japanese firms alone employed 400 Ainos to catch and dry it. It is never taken in nets, but buckets are used at ebb-tide.

After having surveyed Patience Gulf, which had only been partially examined by the Dutchman Vries, and at the bottom of which flows a stream now named the Neva, Kruzenstern broke off his examination of Saghalien to determine the position of the Kurile Islands, never yet accurately laid down; and on the 5th June, 1805 he returned to Petropaulovski, where he put on shore the ambassador and his suite.

In July, after crossing Nadiejeda Strait, between Matona and Rachona, two of the Kurile Islands, Kruzenstern surveyed the eastern coast of Saghalien, in the neighbourhood of Cape Patience, which presented a very picturesque appearance, with the hills clothed with grass and stunted trees and the shores with bushes. The scenery of the interior, however, was somewhat monotonous, with its unbroken line of lofty mountains.

The navigator skirted along the whole of this deserted and harbourless coast to Capes Maria and Elizabeth, between which is a deep bay, with a little village of thirty-seven houses nestling at the end, the only one the Russians had seen since they left Providence Bay. It was not inhabited by Ainos, but by Tartars, of which very decided proof was obtained a few days later.

Kruzenstern next entered the channel separating Saghalien from Tartary, but he was hardly six miles from the middle of the passage when his soundings gave six fathoms only. It was useless to hope to penetrate further. Orders were given to “’bout ship,” whilst a boat was sent to trace the coast-line on either side, and to explore the middle of the strait until the soundings should give three fathoms only. A very strong current had to be contended with, rendering this row very difficult, and this current was rightly supposed to be due to the River Amoor, the mouth of which was not far distant.

The advice given to Kruzenstern by the Governor of Kamtchatka, not to approach the coast of Chinese Tartary, lest the jealous suspicions of the Celestial Government should be aroused, prevented the explorer from further prosecuting the work of surveying; and once more passing the Kurile group, the Nadiejeda returned to Petropaulovsky.

The Commander availed himself of his stay in this port to make some necessary repairs in his vessel, and to confirm the statements of Captain Clerke, who had succeeded Cook in the command of his last expedition, and those of Delisle de la Croyère, the French astronomer, who had been Behring’s companion in 1741.

During this last sojourn at Petropaulovsky, Kruzenstern received an autograph letter from the Emperor of Russia, enclosing the order of St. Anne as a proof of his Majesty’s satisfaction with the work done.

On the 4th October, 1805, the Nadiejeda set sail for Europe; exploring en route the latitudes in which, according to the maps of the day, were situated the islands of Rica-de-Plata, Guadalupas, Malabrigos, St. Sebastian de Lobos, and San Juan.

Kruzenstern next identified the Farellon Islands of Anson’s map, now known as St. Alexander, St. Augustine, and Volcanos, and situated south of the Bonin-Sima group. Then crossing the Formosa Channel, he arrived at Macao on the 21st November.

He was a good deal surprised not to find the Neva there, as he had given instructions for it to bring a cargo of furs, the price of which he proposed expending on Chinese merchandise. He decided to wait for the arrival of the Neva.

Macao seemed to him to be falling rapidly into decay.

“Many fine buildings,” he says, “are ranged in large squares, surrounded by courtyards and gardens; but most of them uninhabited, the number of Portuguese residents there having greatly decreased. The chief private houses belong to the members of the Dutch and English factories…. Twelve or fifteen thousand is said to be the number of the inhabitants of Macao, most of whom, however, are Chinese, who have so completely taken possession of the town, that it is rare to meet any European in the streets, with the exception of priests and nuns. One of the inhabitants said to me, ‘We have more priests here than soldiers;’ a piece of raillery that was literally true, the number of soldiers amounting only to 150, not one of whom is a European, the whole being mulattos of Macao and Goa. Even the officers are not all Europeans. With so small a garrison it is difficult to defend four large fortresses; and the natural insolence of the Chinese finds a sufficient motive in the weakness of the military, to heap insult upon insult.”

Just as the Nadiejeda was about to weigh anchor, the Neva at last appeared. It was now the 3rd November, and Kruzenstern went up the coast in the newly arrived vessel as far as Whampoa, where he sold to advantage his cargo of furs, after many prolonged discussions which his firm but conciliating attitude, together with the intervention of English merchants, brought to a successful issue.

On the 9th February, the two vessels once more together weighed anchor, and resumed their voyage by way of the Sunda Isles. Beyond Christmas Island they were again separated in cloudy weather, and did not meet until the end of the trip. On the 4th May, the Nadiejeda cast anchor in St. Helena Bay, sixty days’ voyage from the Sunda Isles and seventy-nine from Macao.

“I know of no better place,” says Kruzenstern, “to get supplies after a long voyage than St. Helena. The road is perfectly safe, and at all times more convenient than Table Bay or Simon’s Bay, at the Cape. The entrance, with the precaution of first getting near the land, is perfectly easy; and on quitting the island nothing more is necessary than to weigh anchor and stand out to sea. Every kind of provision may be obtained here, particularly the best kinds of garden stuffs, and in two or three days a ship may be provided with everything.”

On the 21st April, Kruzenstern passed between the Shetland and Orkney Islands, in order to avoid the English Channel, where he might have met some French pirates, and after a good voyage he arrived at Cronstadt on the 7th August, 1806.

Without taking first rank, like the expedition of Cook or that of La Pérouse, Kruzenstern’s trip was not without interest. We owe no great discovery to the Russian explorer, but he verified and rectified the work of his predecessors. This was in fact what most of the navigators of the nineteenth century had to do, the progress of science enabling them to complete what had been begun by others.

Kruzenstern had taken with him in his voyage round the world the son of the well-known dramatic author Kotzebue. The young Otto Kotzebue, who was then a cadet, soon gained his promotion, and he was a naval lieutenant when, in 1815 the command was given to him of the Rurik, a new brig, with two guns, and a crew of no more than twenty-seven men, equipped at the expense of Count Romantzoff. His task was to explore the less-known parts of Oceania, and to cut a passage for his vessel across the Frozen Ocean. Kotzebue left the port of Cronstadt on the 15th July, 1815, put in first at Copenhagen and Plymouth, and after a very trying trip doubled Cape Horn, and entered the Pacific Ocean on the 22nd January, 1816. After a halt at Talcahuano, on the coast of Chili, he resumed his voyage; sighted the desert island of Salas of Gomez, on the 26th March, and steered towards Easter Island, where he hoped to meet with the same friendly reception as Cook and Pérouse had done before him.

The Russians had, however, hardly disembarked before they were surrounded by a crowd eager to offer them fruit and roots, by whom they were so shamelessly robbed that they were compelled to use their arms in self-defence, and to re-embark as quickly as possible to avoid the shower of stones flung at them by the natives.

The only observation they had time to make during this short visit, was the overthrow of the numerous huge stone statues described, measured, and drawn, by Cook and La Pérouse.

On the 16th April, the Russian captain arrived at the Dog Island of Schouten, which he called Doubtful Island, to mark the difference in his estimate of its position and that attributed to it by earlier navigators. Kotzebue gives it S. lat. 44° 50′ and W. long. 138° 47′.

During the ensuing days were discovered the desert island of Romantzoff, so named in honour of the promoter of the expedition; Spiridoff Island, with a lagoon in the centre; the Island Oura of the Pomautou group, the Vliegen chain of islets, and the no less extended group of the Kruzenstern Islands.

On the 28th April, the Rurik was near the supposed site of Bauman’s Islands, but not a sign of them could be seen, and it appeared probable that the group had in fact been one of those already visited.

As soon as he was safely out of the dangerous Pomautou archipelago Kotzebue steered towards the group of islands sighted in 1788 by Sever, who, without touching at them, gave them the name of Penrhyn. The Russian explorer determined the position of the central group of islets as S. lat. 9° 1′ 35″ and W. long. 157° 44′ 32″, characterizing them as very low, like those of the Pomautou group, but inhabited for all that.

At the sight of the vessel a considerable fleet of canoes put off from the shore, and the natives, palm branches in their hands, advanced with the rhythmic sound of the paddles serving as a kind of solemn and melancholy accompaniment to numerous singers. To guard against surprise, Kotzebue made all the canoes draw up on one side of the vessel, and bartering was done with a rope as the means of communication. The natives had nothing to trade with but bits of iron and fish-hooks made of mother-of-pearl. They were well made and martial-looking, but wore no clothes beyond a kind of apron.

At first only noisy and very lively, the natives soon became threatening. They thieved openly, and answered remonstrances with undisguised taunts. Brandishing their spears above their heads, they seemed to be urging each other on to an attack.

When Kotzebue felt that the moment had come to put an end to these hostile demonstrations, he had one gun fired. In the twinkling of an eye the canoes were empty, their terrified crews unpremeditatingly flinging themselves into the water with one accord. Presently the heads of the divers reappeared, and, a little calmed down by the warning received, the natives returned to their canoes and their bartering. Nails and pieces of iron were much sought after by these people, whom Kotzebue likens to the natives of Noukha-Hiva. They do not exactly tatoo themselves, but cover their bodies with large scars.

A curious fashion not before noticed amongst the islanders of Oceania prevails amongst them. Most of them wear the nails very long, and those of the chief men in the canoes extended three inches beyond the end of the finger.

Thirty-six boats, manned by 360 men, now surrounded the vessel, and Kotzebue, judging that with his feeble resources and the small crew of the Rurik any attempt to land would be imprudent, set sail again without being able to collect any more information on these wild and warlike islanders.

Continuing his voyage towards Kamtchatka, the navigator sighted on the 21st May two groups of islands connected by a chain of coral reefs. He named them Kutusoff and Suwaroff, determined their position, and made up his mind to come back and examine them again. The natives in fleet canoes approached the Rurik, but, in spite of the pressing invitation of the Russians, would not trust themselves on board. They gazed at the vessel in astonishment, talked to each other with a vivacity which showed their intelligence, and flung on deck the fruit of the pandanus-tree and cocoa-nuts.

Their lank black hair, with flowers fastened in it here and there, the ornaments hung round their necks, their clothing of “two curiously-woven coloured mats tied to the waist” and reaching below the knee, but above all their frank and friendly countenances, distinguished the natives of the Marshall archipelago from those of Penrhyn.

On the 19th June the Rurik put in at New Archangel, and for twenty-eight days her crew were occupied in repairing her.

On the 15th July Kotzebue set sail again, and five days later disembarked on Behring Island, the southern promontory of which he laid down in N. lat. 55° 17′ 18″ and W. long. 194° 6′ 37″.

The natives Kotzebue met with on this island, like those of the North American coast, wore clothes made of seal-skin and the intestines of the walrus. The lances used by them were pointed with the teeth of these amphibious animals. Their food consisted of the flesh of whales and seals, which they store in deep cellars dug in the earth. Their boats were made of leather, and they had sledges drawn by dogs.

Their mode of salutation is strange enough, they first rub each other’s noses and then pass their hands over their own stomachs as if rejoicing over the swallowing of some tid-bit. Lastly, when they want to be very friendly indeed, they spit in their own palms and rub their friends’ faces with the spittle.

The captain, still keeping his northerly course along the American coast, discovered Schichmareff Bay, Saritschiff Island, and lastly, an extensive gulf, the existence of which was not previously known. At the end of this gulf Kotzebue hoped to find a channel through which he could reach the Arctic Ocean, but he was disappointed. He gave his own name to the gulf, and that of Kruzenstern to the cape at the entrance.

Driven back by bad weather, the Rurik reached Ounalashka on the 6th September, halted for a few days at San Francisco, and reached the Sandwich Islands, where some important surveys were made and some very curious information collected.

On leaving the Sandwich Islands, Kotzebue steered for Suwaroff and Kutusoff Islands, which he had discovered a few months before. On the 1st January, 1817, he sighted Miadi Island, to which he gave the name of New Year’s Island. Four days later he discovered a chain of little low wooded islands set in a framework of reefs, through which the vessel could scarcely make its way.

Just at first the natives ran away at the sight of Lieutenant Schischmaroff, but they soon came back with branches in their hands, shouting out the word aidara (friend). The officer repeated this word and gave them a few nails in return, for which the Russians received the collars and flowers worn as neck-ornaments by the natives.

This exchange of courtesies emboldened the rest of the islanders to appear, and throughout the stay of the Russians in this archipelago these friendly demonstrations and enthusiastic but guarded greetings were continued. One native, Rarik by name, was particularly cordial to the Russians, whom he informed that the name of his island and of the chain of islets and attolls2 connected with it was Otdia. In acknowledgment of the cordial reception of the natives, Kotzebue left with them a cock and hen, and planted in a garden laid out under his orders a quantity of seeds, in the hope that they would thrive; but in this he did not make allowance for the number of rats which swarmed upon these islands and wrought havoc in his plantations.

2 Attolls are coral islands like circular belts surrounding a smooth lagoon.—Trans.

On the 6th February, after ascertaining from what he was told by a chief named Languediak, that these sparsely populated islands were of recent formation, Kotzebue put to sea again, having first christened the archipelago Romantzoff.

The next day a group of islets, on which only three inhabitants were found, had its name of Eregup changed to that of Tchitschakoff, and then an enthusiastic reception was given to Kotzebue on the Kawen Islands by the tamon or chief. Every native here fêted the new-comers, some by their silence—like the queen forbidden by etiquette to answer the speeches made to her—some by their dances, cries, and songs, in which the name of Totabou (Kotzebue) was constantly repeated. The chief himself came to fetch Kotzebue in a canoe, and carried him on his shoulders through the breakers to the beach.

In the Aur group the navigator noticed amongst a crowd of natives who climbed on to the vessel, two natives whose faces and tattooing seemed to mark them as of alien race. One of them, Kadu by name, especially pleased the commander, who gave him some bits of iron, and Kotzebue was surprised that he did not receive them with the same pleasure as his companions. This was explained the same evening. When all the natives were leaving the vessel, Kadu earnestly begged to be allowed to remain on the Rurik, and never again to leave it. The commander only yielded to his wishes after a great deal of persuasion.

“Kadu,” says Kotzebue, “had scarcely obtained permission, when he turned quickly to his comrades, who were waiting for him, declared to them his intention of remaining on board the ship, and distributed his iron among the chiefs. The astonishment in the boats was beyond description: they tried in vain to shake his resolution; he was immovable. At last his friend Edock came back, spoke long and seriously to him, and when he found that his persuasion was of no avail, he attempted to drag him by force; but Kadu now used the right of the strongest, he pushed his friend from him, and the boats sailed off. His resolution being inexplicable to me, I conceived a notion that he perhaps intended to steal during the night, and privately to leave the ship, and therefore had the night-watch doubled, and his bed made up close to mine on the deck, where I slept, on account of the heat. Kadu felt greatly honoured to sleep close to the tamon of the ship.”

Born at Ulle, one of the Caroline Islands, more than 300 miles from the group where he was now living, Kadu, with Edok and two other fellow-countrymen, had been overtaken, when fishing, by a violent storm. For eight months the poor fellows were at the mercy of the winds and currents on a sea now smooth, now rough. They had never throughout this time been without fish, but they had suffered the cruelest tortures from thirst. When their stock of rain-water, which they had used very sparingly, was exhausted, there was nothing left to them to do but to fling themselves into the sea and try to obtain at the bottom of the ocean some water less impregnated with salt, which they brought to the surface in cocoa-nut shells pierced with a small opening. When they reached the Aur Islands, even the sight of land and the immediate prospect of safety did not rouse them from the state of prostration into which they had sunk.

The sight of the iron instruments in the canoe of the strangers led the people of Aur to decide on their massacre for the sake of their treasures; but the tamon, Tigedien by name, took them under his protection.

Three years had passed since this event, and the men from the Caroline Islands, thanks to their more extended knowledge, soon acquired a certain ascendancy over their hosts.

When the Rurik appeared, Kadu was in the woods a long way from the coast. He was sent for at once, as he was looked upon as a great traveller, and he might perhaps be able to say what the great monster approaching the island was. Now Kadu had more than once seen European vessels, and he persuaded his friends to go and meet the strangers, and to receive them kindly.

Such had been Kadu’s adventures. He now remained on the Rurik, identified the other islands of the Archipelago, and lost no time in facilitating intercourse between the Russians and the natives. Dressed in a yellow mantle, and wearing a red cap like a convict, Kadu looked down upon his old friends, and seemed not to recognize them. When a fine old man with a flowing beard, named Tigedien, came on board, Kadu undertook to explain to him and his companions the working of the vessel and the use of everything about the ship. Like many Europeans, he made up for his ignorance by imperturbable assurance, and had an answer ready for every question.

Interrogated on the subject of a little box from which a sailor took a black powder and applied it to his nostrils, Kadu glibly told some most extraordinary stories, and wound up with a practical illustration by putting the box against his own nose. He then flung it from him, sneezing violently and screaming so loud that his terrified friends fled away on every side; but when the crisis was over he managed to turn the incident to his own advantage.

Kadu gave Kotzebue some general information about the group of islands then under examination, and the Russians spent a month in taking surveys, &c. All these islands, which the natives call Radack, were under the control of one tamon, a man named Lamary. A few years later Dumont d’Urville gave the name of Marshall to the group. According to Kadu, another chain of islets, attolls, and reefs was situated some little distance off on the west.

Kotzebue had not time to identify them, and steering in a northerly direction he reached Ounalashka on the 24th April, where he had to repair the serious damage sustained by the Rurik in two violent storms. This done, he took on board some baidares (boats cased in skins to make them water-tight), with fifteen natives of the Aleutian Islands, who were used to the navigation of the Polar seas, and resumed his exploration of Behring Strait.

Kotzebue had suffered very much from pain in his chest ever since when, doubling Cape Horn, he had been knocked down by a huge wave and flung overboard, an accident which would have cost him his life had he not clung to some rope. The consequences were so serious to his health that when, on the 10th July, he landed on the island of St. Lawrence, he was obliged to give up the further prosecution of his researches.

On the 1st October the Rurik made a second short halt at the Sandwich Islands where seeds and animals were landed, and at the end of the month the explorers landed at Otdia in the midst of the enthusiastic acclamations of the natives. The cats brought by the visitors were welcomed with special enthusiasm, for the island was infested with immense numbers of rats, who worked havoc on the plantations. Great also was the rejoicing over the return of Kadu, with whom the Russians left an assortment of tools and weapons, which made their owner the wealthiest inhabitant of the archipelago.

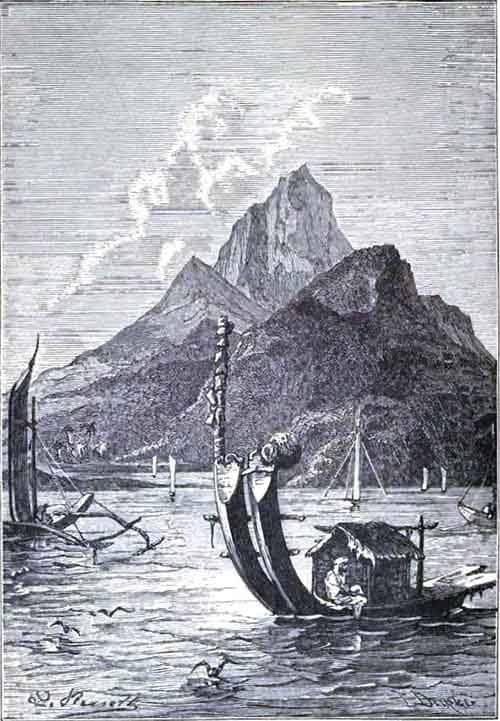

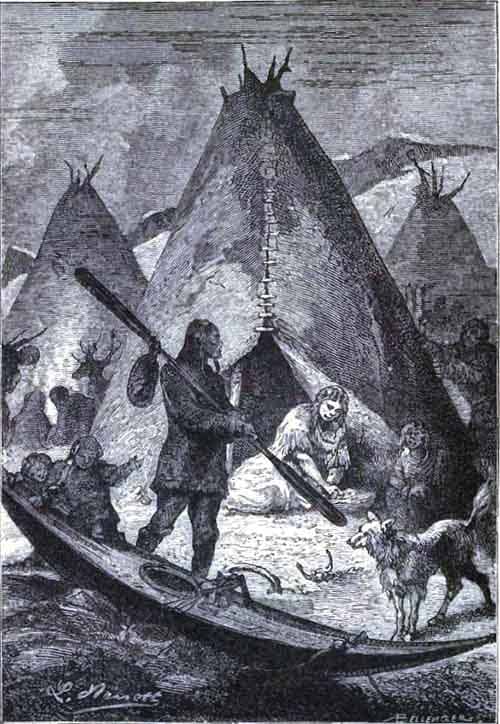

(Fac-simile of early engraving.)

On the 4th November the Rurik left the Radak Islands, after identifying the Legiep group, and cast anchor off Guam, one of the Marianne islands, where she remained until the end of the month. A halt of some weeks at Manilla enabled the commander to collect some curious information about the Philippine Islands, to which he would have to return later.

After escaping from the violent storms encountered in doubling the Cape of Good Hope, the Rurik cast anchor on the 3rd August, 1818, in the Neva, opposite Count Romantzoff’s palace.

These three years of absence had been turned to good account by the hardy navigators. In spite of the smallness of their number and the poverty of their equipments, they had not been afraid to face the terrors of the deep, to venture amongst all but unknown archipelagoes, or to brave the rigours of the Arctic and Torrid zones. Important as were their actual discoveries, their rectification of the errors of their predecessors were of yet greater value. Two thousand five hundred species of plants, one third of which were quite new, with numerous details respecting the language, ethnography, religion, and customs of the tribes visited, formed a rich harvest attesting the zeal, skill, and knowledge of the captain as well as the intrepidity and endurance of his crew.

When, therefore, the Russian government decided, in 1823, to send reinforcements to Kamtchatka to put an end to the contraband trade carried on in Russian America, the command of the expedition was given to Kotzebue. A frigate called the Predpriatie was placed at his disposal, and he was left free to choose his own route both going and returning.

Kotzebue had gone round the world as a midshipman with Kruzenstern, and that explorer now entrusted to him his eldest son, as did also Möller, the Minister of Marine, a proof of the great confidence both fathers placed in him.

The expedition left Cronstadt on the 15th August, 1823, reached Rio Janeiro in safety, doubled Cape Horn on the 15th January, 1824, and steered for the Pomautou Archipelago, where Predpriatie Island was discovered and the islands of Araktschejews, Romantzoff, Carlshoff, and Palliser were identified. On the 14th March anchor was cast in the harbour of Matavar, Otaheite.

Since Cook’s stay in this archipelago a complete transformation had taken place in the manners and customs of the inhabitants.

In 1799 some missionaries settled in Otaheite, where they remained for ten years, unfortunately without making a single conversion, and we add with regret without even winning the esteem or respect of the natives. Compelled at the end of these ten years, in consequence of the revolutions which convulsed Otaheite, to take refuge at Eimeo and other islands of the same group, their efforts were there crowned with more success. In 1817, Pomaré, king of Otaheite, recalled the missionaries, made them a grant of land, and declared himself a convert to Christianity. His example was soon followed by a considerable number of natives.

Kotzebue had heard of this change, but he was not prepared to find European customs generally adopted.

At the sound of the discharge announcing the arrival of the Russians, a boat, bearing the Otaheitian flag, put off from shore, bringing a pilot to guide the Predpriatie to its anchorage.

The next day, which happened to be Sunday, the Russians were surprised at the religious silence which prevailed throughout the island when they landed. This silence was only broken by the sound of canticles and psalms sung by the natives in their huts.

The church, a plain, clean building of rectangular form, roofed with reeds and approached by a long avenue of palms, was well filled with an attentive, orderly congregation, the men sitting on one side, the women on the other, all with prayer-books in their hands. The voices of the neophytes often joined in the chant of the missionaries, unfortunately with better will than correctness or appropriateness.

If the piety of the islanders was edifying, the costumes worn by these strange converts were such as somewhat to distract the attention of the visitors. A black coat or the waistcoat of an English uniform was the only garment worn by some, whilst others contented themselves with a jacket, a shirt, or a pair of trousers. The most fortunate were wrapped in cloth mantles, and rich and poor alike dispensed with shoes and stockings.

The women were no less grotesquely clad. Some wore men’s shirts, white or striped as the case might be, others a mere piece of cloth; but all had European hats. The wives of the Areois3 wore coloured robes, a piece of great extravagance, but with them the dress formed the whole costume.

3 The Areois are a curious vagrant set of people, who have been found in these regions, who practise the singular and fatal custom of killing their children at birth, because of a traditional law binding them to do so.—Trans.

On the Monday a most imposing ceremony took place. This was the visit to Kotzebue of the queen-mother and the royal family. These great people were preceded by a master of ceremonies, who was a sort of court fool wearing nothing but a red waistcoat, and with his legs tattooed to represent striped trousers, whilst on the lower portion of his back was described a quadrant divided into minute sections. He performed his absurd capers, contortions, and grimaces with a gravity infinitely amusing.

The queen regent carried the little king Pomaré III. in her arms, and beside her walked his sister, a pretty child of ten years old. The royal infant was dressed in European style, like his subjects, and like them, he wore nothing on his feet. At the request of the ministers and great people of Otaheite, Kotzebue had a pair of boots made for him, which he was to wear on the day of his coronation.

Great were the shouts of joy, the gestures of delight, and the envious exclamations over the trifles distributed amongst the ladies of the court, and fierce were the struggles for the smallest shreds of the imitation gold lace given away.

What important matter could have brought so many men on to the deck of the frigate, bearing with them quantities of fruits and figs? These eager messengers were the husbands of the disappointed ladies of Otaheite who had not been present at the division of the gold lace more valuable in their eyes than rivers of diamonds in those of Europeans.

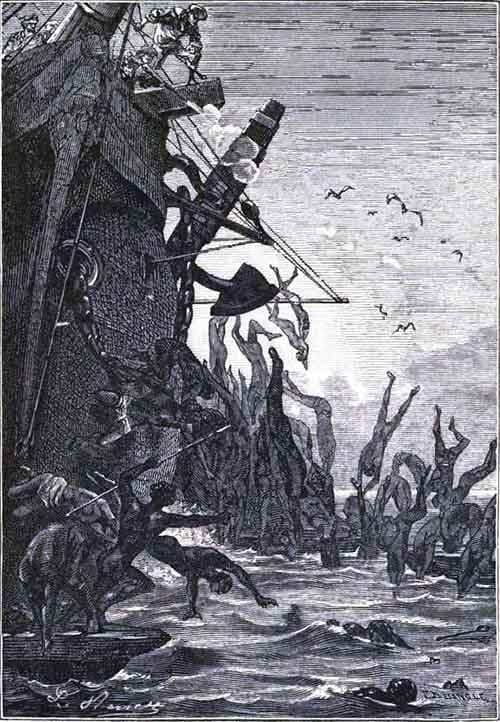

At the end of ten days, Kotzebue decided to leave this strange country, where civilization and barbarism flourished side by side in a manner so fraternal, and steered for the Samoa Archipelago, notorious for the massacre of the companions of La Pérouse.

How great was the difference between the Samoans and the Otaheitians! Wild and fierce, suspicious and threatening, the natives of Rose Island could scarcely be kept off the deck of the Predpriatie, and one of them at the sight of the bare arm of a sailor made a savage and eloquent gesture showing with what pleasure he could devour the firm and doubtless savoury flesh displayed to view.

The insolence of the natives increased with the arrival of more canoes from the shore, and they had to be beaten back with boathooks before the Predpriatie could get away from amongst the frail boats of the ferocious islanders.

Upolu or Oyalava, Platte and Pola or Savai Islands, which with Rose Island form part of the Navigator or Samoan group, were passed almost as soon as they were sighted; and Kotzebue steered for the Radak Islands, where he had been so kindly received on his first voyage. This time, however, the natives were terrified at sight of the huge vessel, and piled up their canoes or fled into the interior, whilst on the beach a procession was formed, a number of islanders with palm branches in their hands advancing to meet the intruders and beg for peace.

At this sight, Kotzebue flung himself into a boat with the surgeon Eschscholtz, and rowing rapidly towards the shore, shouted: “Totabou aïdara” (Kotzebue, friend). An immediate change was the result; the petitions the natives were going to address to the Russians were converted into shouts and enthusiastic demonstrations of delight, some rushing forwards to welcome their friend, others running over to announce his arrival to their fellow-countrymen.

The commander was very pleased to find that Kadu was still living at Aur, under the protection of Lamary, whose countenance he had secured at the price of half his wealth.

Of all the animals left here by Kotzebue, the cats, now become wild alone, had survived, and thus far they had not destroyed the legions of rats with which the island was overrun.

The explorer remained several days with his friends, whom he entertained with dramatic representations; and on the 6th May he made for the Legiep group, the examination of which he had left uncompleted on his last voyage. After surveying it, he intended to resume his exploration of the Radak Islands, but bad weather prevented this, and he had to set sail for Kamtchatka.

The crew here enjoyed the rest so fully earned, from the 7th June to the 20th July, when Kotzebue set sail for New Archangel on the American coast, where he cast anchor on the 7th August.

The frigate, which was here to take the place of the Predpriatie, was not however ready for sea until the 1st March of the following year, and Kotzebue turned the delay to account by visiting the Sandwich Islands, where he cast anchor off Waihou in December, 1824.

The harbour of Hono-kourou or Honolulu is the safest of the archipelago; a good many vessels therefore put in there even at this early date, and the island of Waihou bid fair to become the most important of the group, supplanting Hawaii or Owhyee. The appearance of the town was already semi-European, stone houses replaced the primitive native huts, regular streets with shops, café, public-houses, much patronized by the sailors of whalers and fur-traders, together with a fortress provided with cannon, were the most noteworthy signs of the rapid transformation of the manners and customs of the natives.

Fifty years had now elapsed since the discovery of most of the islands of Oceania, and everywhere changes had taken place as sudden as those in the Sandwich Islands.

“The fur trade,” says Desborough Cooley, carried on with the north-west coast of America, “has effected a wonderful revolution in the Sandwich Islands, which from their situation offered an advantageous shelter for ships engaged in it. Among these islands the fur-traders wintered, refitted their vessels, and replenished their stock of fresh provisions; and, as summer approached, returned to complete their cargo on the coast of America. Iron tools and, above all, guns were eagerly sought for by the islanders in exchange for their provisions; and the mercenery traders, regardless of consequences, readily gratified their desires. Fire-arms and ammunition being the most profitable stock to traffic with were supplied them in abundance. Hence the Sandwich islanders soon became formidable to their visitors; they seized on several small vessels, and displayed an energy tinctured at first with barbarity, but indicating great capabilities of social improvement. At this period, one of those extraordinary characters which seldom fail to come forth when fate is charged with great events, completed the revolution, which had its origin in the impulse of Europeans. Tame-tame-hah, a chief, who had made himself conspicuous during the last and unfortunate visit of Cook to those islands, usurped the authority of king, subdued the neighbouring islands with an army of 16,000 men, and made his conquests subservient to his grand schemes of improvement. He knew the superiority of Europeans, and was proud to imitate them. Already, in 1796, when Captain Broughton visited those islands, the usurper sent to ask him whether he should salute him with great guns. He always kept Englishmen about him as ministers and advisers. In 1817, he is said to have had an army of 7000 men, armed with muskets, among whom were at least fifty Europeans. Tame-tame-hah, who began his career in blood and usurpation, lived to gain the sincere love and admiration of his subjects, who regarded him as more than human, and mourned his death with tears of warmer affection than often bedew the ashes of royalty.”

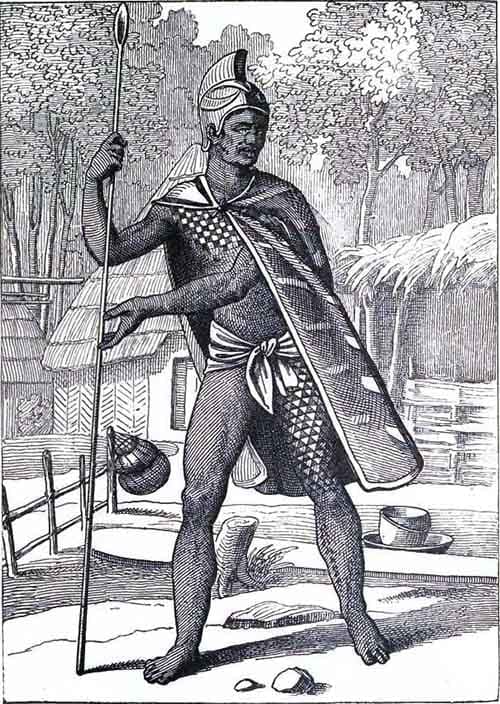

(Fac-simile of early engraving.)

Such was the state of things when the Russian expedition put in at Waihou. The young king Rio-Rio was in England with his wife, and the government of the archipelago was in the hands of the queen-mother, Kaahou Manou.

Kotzebue took advantage of the latter and of the first minister both being absent on a neighbouring island, to pay a visit to another wife of Kamea-Mea.

“The apartment,” says the traveller, “was furnished in the European fashion, with chairs, tables, and looking-glasses. In one corner stood an immensely large bed with silk curtains; the floor was covered with fine mats, and on these, in the middle of the room, lay Nomahanna, extended on her stomach, her head turned towards the door, and her arms supported on a silk pillow…. Nomahanna, who appeared at the utmost not more than forty years old, was exactly six feet two inches high, and rather more than two ells in circumference…. Her coal-black hair was neatly plaited, at the top of a head as round as a ball; her flat nose and thick projecting lips were certainly not very handsome, yet was her countenance on the whole prepossessing and agreeable.”

The “good lady” remembered having seen Kotzebue ten years before. She, therefore, received him graciously, but she could not speak of her husband without tears in her eyes, and her grief did not appear to be assumed. In order that the date of his death should be ever-present to her mind she had had the inscription 6th May, 1819, branded on her arm.

A zealous Christian, like most of the population, the queen took Kotzebue to the church, a vast but simple building, not nearly so crowded as that at Otaheite. Nomahanna seemed to be very intelligent, she knew how to read and was specially enthusiastic about writing, that art which connects us with the absent. Being anxious to give the commander a proof alike of her affection and of her acquirements she sent him a letter by hand which it had taken her several weeks to concoct.

The other ladies did not like to be outdone, and Kotzebue found himself overwhelmed with documents. The only means to check this epistolatory inundation was to weigh anchor, which the captain did without loss of time.

Before his departure he received queen Nomahanna on board. Her Majesty appeared in her robes of ceremony, consisting of a magnificent peach-coloured silk dress embroidered with black, evidently originally made for a European, and consequently too tight and too short for its wearer. People could, therefore, see not only the feet, beside which those of Charlemagne would have looked like a Chinaman’s, and which were cased in huge men’s boots, but also a pair of fat, brown, naked legs resembling the balustrades of a terrace. A collar of red and yellow feathers, a garland of natural flowers, serving as a gorget, and a hat of Leghorn straw, trimmed with artificial flowers, completed this fine but absurd costume.

Nomahanna went over the ship, asking questions about everything, and at last, worn out with seeing so many wonders, betook herself to the captain’s cabin, where a good collation was spread for her. The queen flung herself upon a couch, but the fragile article of furniture was unable to sustain so much majesty, and gave way beneath the weight of a princess, whose embonpoint had doubtless had a good deal to do with her elevation to such high rank.

After this halt Kotzebue returned to New Archangel, where he remained until the 30th July, 1825. He then paid another visit to the Sandwich Islands a short time after Admiral Byron had brought back the remains of the king and queen. The archipelago was then at peace, its prosperity was continually on the increase, the influence of the missionaries was confirmed, and the education of the young monarch was in the hands of Missionary Bingham. The inhabitants were deeply touched by the honours accorded by the English to the remains of their sovereigns, and the day seemed to be not far distant when European customs would completely supersede those of the natives.

Some provisions having been embarked at Waihou, the explorer made for Radak Islands, identified the Pescadores, forming the southern extremity of that chain, discovered the Eschscholtz group, a short distance off, and touched at Guam on the 15th October. On the 23rd January, 1826, he left Manilla after a stay of some months, during which constant intercourse with the natives had enabled him to add greatly to our knowledge of the geography and natural history of the Philippine islands. A new Spanish governor had arrived with a large reinforcement of troops, and had so completely crushed all agitation that the colonists had quite given up their scheme of separating themselves from Spain.

On the 10th July, 1826, the Predpriatie returned to Cronstadt, after a voyage extending over three years, during which she had visited the north-west coast of America, the Aleutian Islands, Kamtchatka, and the Sea of Oktoksh; surveyed minutely a great part of the Radak Islands, and obtained fresh information on the changes through which the people of Oceania were passing. Thanks to the ardour of Chamisso and Professor Eschscholtz, many specimens of natural history had been collected, and the latter published a description of more than 2000 animals, as well as some curious details on the mode of formation of the Coral islands in the South Seas.

The English government had now resumed with eagerness the study of the tantalizing problem, the solution of which had been sought so long in vain. We allude to the finding of the north-west passage. When Parry by sea and Franklin by land were trying to reach Behring Strait, Captain Frederick William Beechey received instructions to penetrate as far north as possible by way of the same strait so as to meet the other explorers, who would doubtless arrive in a state of exhaustion from fatigue and privation.

The Blossom, Captain Beechey commander, set sail from Spithead on the 19th May, 1825, and after doubling Cape Horn on the 26th December, entered the Pacific Ocean. After a short stay off the coast of Chili, Beechey visited Easter Island, where the same incidents which had marked Kotzebue’s visit were repeated. The same eager reception on the part of the natives, who swam to the Blossom or brought their paltry merchandise to it in canoes, and the same shower of stones and blows from clubs when the English landed, repulsed, as in the Russian explorer’s time, with a rapid discharge of shot.

On the 4th December, Captain Beechey sighted an island completely overgrown with vegetation. This was the spot famous for the discovery on it of the descendants of the mutineers of the Bounty, who landed on it after the enactment of a tragedy, which at the end of last century had excited intense public interest in England.

In 1781 Lieutenant Bligh, one of the officers who had distinguished himself under Cook, was appointed to the command of the Bounty, and received orders to go to Otaheite, there to obtain specimens of the breadfruit-tree and other of its vegetable productions for transportation to the Antilles, then generally known amongst the English as the Western Indies. After doubling Cape Horn, Bligh cast anchor in the Bay of Matavai, where he shipped a cargo of breadfruit-trees, proceeding thence to Ramouka, one of the Tonga Isles, for more of the same valuable growth. Thus far no special incident marked the course of the voyage, which seemed likely to end happily. But the haughty character and stern, despotic manners of the commander had alienated from him the affections of nearly the whole of his crew. A plot was formed against him which was carried out before sunrise on the 28th April, off Tofona.

Surprised by the mutineers whilst still in bed, Bligh was bound and gagged before he could defend himself, and dragged on deck in his night-shirt, and after a mock trial, presided over by Lieutenant Christian Fletcher, he, with eighteen men who remained faithful to him, was lowered into a boat containing a few provisions, and abandoned in the open sea.

After enduring agonies of hunger and thirst, and escaping from terrible storms and from the teeth of the savage natives of Tofona, Bligh succeeded in reaching Timor Island, where he received an enthusiastic welcome.

“I now desired my people to come on shore,” says Bligh, “which was as much as some of them could do, being scarce able to walk; they, however, were helped to the house, and found tea with bread and butter provided for their breakfast…. Our bodies were nothing but skin and bones, our limbs were full of sores, and we were clothed in rags; in this condition, with the tears of joy and gratitude flowing down our cheeks, the people of Timor beheld us with a mixture of horror, surprise, and pity…. Thus, through the assistance of Divine Providence, we surmounted the difficulties and distresses of a most perilous voyage.”

Perilous, indeed, for it had lasted no less than forty-one days in latitudes but little known, in an open boat, with insufficient food, want and exposure causing infinite suffering. Yet in this voyage of more than 1500 leagues but one man was lost, a sailor who fell a victim at the beginning of the journey to the natives of Tofona.

The fate of the mutineers was strange, and more than one lesson may be learnt from it.

They made for Otaheite, where provisions were obtained, and those who had been least active in the mutiny were abandoned, and thence Christian set sail with eight sailors, who elected to remain with him, and some twenty-two natives, men and women from Otaheite and Toubonai. Nothing more was heard of them!

As for those who remained at Otaheite, they were taken prisoners in 1791 by Captain Edwards of the Pandora, sent out by the English Government in search of them and the other mutineers, with orders to bring them to England. Of the ten who were brought home by the Pandora, only three were condemned to death.

Twenty years passed by before the slightest light was thrown on the fate of Christian and those he took with him.

In 1808 an American trading-vessel touched at Pitcairn, there to complete her cargo of seal-skins. The captain imagined the island to be uninhabited, but to his very great surprise a canoe presently approached his ship manned by three young men of colour, who spoke English very well. Greatly astonished, the commander questioned them, and learnt that their father had served under Bligh.

The fate of the latter was now known to the whole world, and its discussion had lightened the tedious hours in the forecastles of vessels of every nationality, and the American captain, reminded by the singular incident related above of the disappearance of so many of the mutineers of the Bounty, landed on the island, where he met an Englishman named Smith, who had belonged to the crew of that vessel, and who made the following confession.

When he left Otaheite, Christian made direct for Pitcairn, attracted to it by its lonely situation, south of the Pomautou Islands, and out of the general track of vessels. After landing the provisions of the Bounty and taking away all the fittings which could be of any use, the mutineers burnt the vessel not only with a view to removing all trace of their whereabouts, but also to prevent the escape of any of their number.

From the first the sight of the extensive marshes led them to believe the island to be uninhabited, and they were soon convinced of the justice of this opinion. Huts were built and land was cleared; but the English charitably assigned to the natives, whom they had carried off or who had elected to join them, the position of slaves. Two years passed by without any serious dissensions arising, but at the end of that time the natives laid a plot against the whites, of which, however, the latter were informed by an Otaheitan woman, and the two leaders paid for their abortive attempt with their lives.

Two more years of peace and tranquillity ensued, and then another plot was laid, this time resulting in the massacre of Christian and five of his comrades. The murder, however, was avenged by the native women, who mourned for their English lovers and killed the surviving men of Otaheite.

A little later the discovery of a plant, from which a kind of brandy could be made, caused the death of one of the four Englishmen still remaining, another was murdered by his companions, a third died a natural death, and the last one, Smith, took the name of Adams and lived on at the head of a community, consisting of ten women and nineteen children, the eldest of whom were but seven or eight years old.

This man, who had reflected on his errors and repented of them, now led a new life, fulfilling the duties of father, priest, and sovereign, his combined firmness and justice acquiring for him an all-powerful influence over his motley subjects.

This strange teacher of morality, who in his youth had set all laws at defiance, and to whom no obligation was sacred, now preached pity, love, and sympathy, arranged regular marriages between the children of different parents, his little community thriving lustily under the mild yet firm control of one who had but lately turned from his own evil ways.

Such at the time of Beechey’s arrival was the state of the colony at Pitcairn. The navigator, well received by the inhabitants, whose virtuous conduct recalled the golden age, remained amongst them eighteen days. The village consisted of clean, well-built huts, surrounded by pandanus and cocoa-palms; the fields were well cultivated, and under Adams’ tuition the young people had made implements of agriculture of really extraordinary excellence. The faces of these half breeds were good-looking and pleasant in expression, and their figures were well-proportioned, showing unusual muscular development.

After leaving Pitcairn, Beechey visited Crescent, Gambier, Hood, Clermont, Tonnerre, Serles, Whitsunday, Queen-Charlotte, Tehaï, and the Lancer Islands, all in the Pomautou group, and an islet to which he gave the name of Byam-Martin.

Here the explorer met a native named Ton-Wari, who had been shipwrecked in a storm. Having left Anaa with 500 fellow-countrymen in three canoes to render homage to Pomaré III., who had just ascended the throne, Ton-Wari had been driven out of his course by westerly winds. These were succeeded by variable breezes, and provisions were soon so completely exhausted that the survivors had to feed on the bodies of those who were the first to succumb. Finally Ton-Wari arrived at Barrow Island in the centre of the Dangerous Archipelago, where he obtained a small stock of provisions, and after a long delay, his canoe having been stove in off Byam-Martin, once more put to sea.

Beechey yielded under considerable persuasion to Ton-Wari’s entreaty to be received on board with his wife and children and taken to Otaheite. The next day, by one of those strange chances seldom occurring except in fiction, Beechey stopped at Heïon, where Ton-Wari met his brother, who had supposed him to be long since dead. After the first transports of delight and surprise the two natives sat down side by side, and holding each others hands related their several adventures.

Beechey left Heïon on the 10th February, sighted Melville and Croker Islands, and cast anchor on the 18th off Otaheite, where he had some difficulty in obtaining provisions. The natives now demanded good Chilian dollars and European clothing, both of which were altogether wanting on the Blossom.

After receiving a visit from the queen-mother, Beechey was invited to a soirée given in his honour in the palace at Papeïti. When the English arrived, however, they found everybody sound asleep, the hostess having forgotten all about her invitation, and gone to bed earlier than usual. She received her guests none the less cordially however, and organized a little dance in spite of the remonstrances of the missionaries; only the fête had to be conducted so to speak in silence, that the noise might not reach the ears of the police on duty on the beach. From this incident we can guess the amount of liberty the missionary Pritchard allowed to the most exalted personages of Otaheite. What must the discipline then have been for the common herd of the natives!

On the 3rd April the young king paid a visit to Beechey, who gave him, on behalf of the Admiralty, a fine fowling-piece. Very friendly was the intercourse which ensued, and the good influence the English missionaries had obtained was strengthened by the cordiality and tact of the ship’s officers.

Leaving Otaheite on the 26th April, Beechey reached the Sandwich Islands, where he remained some ten days, and then set sail for Behring Strait and the Arctic Ocean. His instructions were to skirt along the North American coast as far as the state of the ice would permit. The Blossom made a halt in Kotzebue Bay, a desolate, forbidding, and inhospitable spot, where the English had several interviews with the natives without obtaining any information about Franklin and his people. At last Beechey sent forward one of the ship’s boats, under command of Lieutenant Elson, to seek the intrepid explorer. Elson was, however, unable to pass Point Barrow (N. lat. 71° 23′) and was compelled to return to the Blossom, which in her turn was driven back to the entrance of the strait by the ice on the 13th October, the weather being clear and the frost of extreme severity.

In order to turn to account the winter season, Beechey visited San Francisco and cast anchor yet again off Honolulu in the Sandwich Islands. Thanks to the liberal and enlightened policy of the government, this archipelago was now rapidly growing in prosperity. The number of houses had increased, the town was gradually acquiring a European appearance, the harbour was frequented by numerous English and American vessels, and a national navy numbering five brigs and eight schooners had sprung into being. Agriculture was in a flourishing condition; coffee, tea, spices, were cultivated in extensive plantations, and efforts were being made to utilize the luxuriant sugar-cane forests native to the archipelago.

After a stay in April at the mouth of the Canton River, the explorers surveyed the Liu-Kiu archipelago, a chain of islands connecting Japan with Formosa, and the Bonin-Sima group, districts in which no animals were seen but big green turtles.