CHAPTER XII.

ELEVEN THOUSAND FEET ALOFT.

The route through Chili had as yet presented no serious obstacles; but now the dangers that attend a journey across the mountains suddenly increased, the struggle with the natural difficulties was about to begin in earnest.

An important question had to be decided before starting. By what pass could they cross the Andes with the least departure from the prescribed course? The catapaz was questioned on this subject.

“I know,” he replied, “of but two passes that are practicable in this part of the Andes.”

“Doubtless the pass of Arica,” said Paganel, “which was discovered by Valdivia Mendoza.”

“Exactly.”

“And that of Villarica, situated to the south of Nevado.”

“You are right.”

“Well, my friend, these two passes have only one difficulty; they will carry us to the south, or the north, farther than we wish.”

“Have you another pass to propose?” asked the major.

“Yes,” replied Paganel; “the pass of Antuco.”

“Well,” said Glenarvan; “but do you know this pass, catapaz?”

“Yes, my lord, I have crossed it, and did not propose it because it is only a cattle-track for the Indian herdsmen of the eastern slopes.”

“Never mind, my friend,” continued Glenarvan; “where the herds of the Indians pass, we can also; and, since this will keep us in our course, let us start for the pass of Antuco.”

The signal for departure was immediately given, and they entered the valley of Los Lejos between great masses of crystalized limestone, and ascended a very gradual slope. Towards noon they had to pass around the shores of a small lake, the picturesque reservoir of all the neighboring streams which flowed into it.

Above the lake extended vast “llanos,” lofty plains, covered with grass, where the herds of the Indians grazed. Then they came upon a swamp which extended to the south and north, but which the instinct of the mules enabled them to avoid. Soon Fort Ballenare appeared on a rocky peak which it crowned with its dismantled walls. The ascent had already become abrupt and stony, and the pebbles, loosened by the hoofs of the mules, rolled under their feet in a rattling torrent.

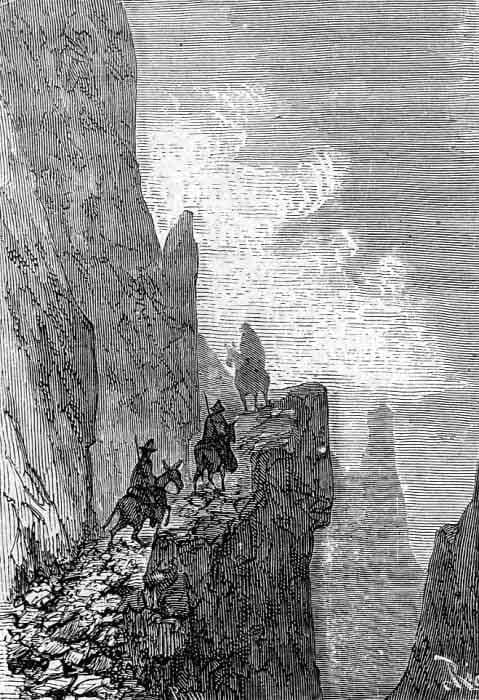

The road now became difficult, and even perilous. The steepness increased, the walls on either side approached each other more and more, while the precipices yawned frightfully. The mules advanced cautiously in single file, with their noses to the ground, scenting the way.

Now and then, at a sudden turn, the madrina disappeared, and the little caravan was then guided by the distant tinkling of her bell. Sometimes, too, the capricious windings of the path would bend the column into two parallel lines, and the catapaz could talk to the peons, while a crevasse, scarcely two fathoms wide, but two hundred deep, formed an impassable abyss between them.

Under these conditions it was difficult to distinguish the course. The almost incessant action of subterranean and volcanic agency changes the road, and the landmarks are never the same. Therefore the catapaz hesitated, stopped, looked about him, examined the form of the rocks, and searched on the crumbling stones for the tracks of Indians.

Glenarvan followed in the steps of his guide. He perceived, he felt, his embarrassment, increasing with the difficulties of the way. He did not dare to question him, but thought that it was better to trust to the instinct of the muleteers and mules.

For an hour longer the catapaz wandered at a venture, but always seeking the more elevated parts of the mountain. At last he was forced to stop short. They were at the bottom of a narrow valley,—one of those ravines that the Indians call “quebradas.” A perpendicular wall of porphyry barred their exit.

The catapaz, after searching vainly for a passage, dismounted, folded his arms, and waited. Glenarvan approached him.

“Have you lost your way?” he asked.

“No, my lord,” replied the catapaz.

“But we are not at the pass of Antuco?”

“We are.”

“Are you not mistaken?”

“I am not. Here are the remains of a fire made by the Indians, and the tracks left by their horses.”

“Well, they passed this way?”

“Yes; but we cannot. The last earthquake has made it impracticable.”

“For mules,” replied the major; “but not for men.”

“That is for you to decide,” said the catapaz. “I have done what I could. My mules and I are ready to turn back, if you please, and search for the other passes of the Andes.”

“But that will cause a delay.”

“Of three days, at least.”

Glenarvan listened in silence to the words of the catapaz, who had evidently acted in accordance with his engagement. His mules could go no farther; but when the proposal was made to retrace their steps, Glenarvan turned towards his companions, and said,—

“Do you wish to go on?”

“We will follow you,” replied Tom Austin.

“And even precede you,” added Paganel. “What is it, after all? To scale a chain of mountains whose opposite slopes afford an unusually easy descent. This accomplished, we can find the Argentine laqueanos, who will guide us across the Pampas, and swift horses accustomed to travel over the plains. Forward, then, without hesitation.”

“Forward!” cried his companions.

“You do not accompany us?” said Glenarvan to the catapaz.

“I am the muleteer,” he replied.

“As you say.”

“Never mind,” said Paganel; “on the other side of this wall we shall find the pass of Antuco again, and I will lead you to the foot of the mountain as directly as the best guide of the Andes.”

Glenarvan accordingly settled with the catapaz, and dismissed him, his peons, and his mules. The arms, the instruments, and the remaining provisions, were divided among the seven travelers. By common consent it was decided that the ascent should be undertaken immediately, and that, if necessary, they should travel part of the night. Around the precipice to the left wound a steep path that mules could not ascend. The difficulties were great; but, after two hours of fatigue and wandering, Glenarvan and his companions found themselves again in the pass of Antuco.

They were now in that part of the Andes properly so called, not far from the main ridge of the mountains; but of the path traced out, of the pass, nothing could be seen. All this region had just been thrown into confusion by the recent earthquakes.

They ascended all night, climbed almost inaccessible plateaus, and leaped over broad and deep crevasses. Their arms took the place of ropes, and their shoulders served as steps. The strength of Mulready and the skill of Wilson were often called into requisition. Many times, without their devotion and courage, the little party could not have advanced.

Glenarvan never lost sight of young Robert, whose youth and eagerness led him to acts of rashness, while Paganel pressed on with all the ardor of a Frenchman. As for the major, he only moved as much as was necessary, no more, no less, and mounted the path by an almost insensible motion. Did he perceive that he had been ascending for several hours? It is not certain. Perhaps he imagined he was descending.

At five o’clock in the morning the travelers had attained a height of seven thousand five hundred feet. They were now on the lower ridges, the last limit of arborescent vegetation. At this hour the aspect of these regions was entirely changed. Great blocks of glittering ice, of a bluish color in certain parts, rose on all sides, and reflected the first rays of the sun.

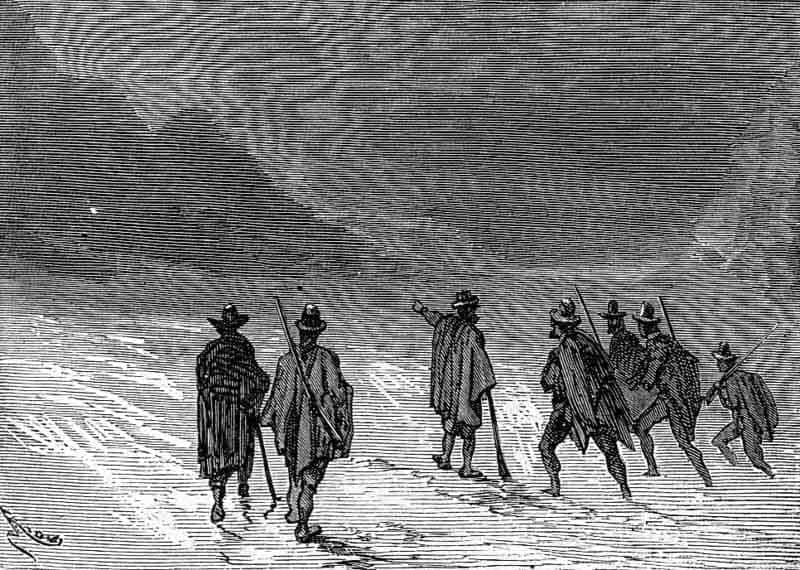

The ascent now became very perilous. They no longer advanced without carefully examining the ice. Wilson had taken the lead, and with his foot tested the surface of the glaciers. His companions followed exactly in his footsteps, and avoided uttering a word, for the least sound might have caused the fall of the snowy masses suspended eight hundred feet above their heads.

They had reached the region of shrubs, which, four hundred and fifty feet higher, gave place to grass and cactuses. At eleven thousand feet all traces of vegetation disappeared. The travelers had stopped only once to recruit their strength by a hasty repast, and with superhuman courage they resumed the ascent in the face of the ever-increasing dangers.

The strength of the little troop, however, in spite of their courage, was almost gone. Glenarvan, seeing the exhaustion of his companions, regretted having engaged in the undertaking. Young Robert struggled against fatigue, but could go no farther.

Glenarvan stopped.

“We must take a rest,” said he, for he clearly saw that no one else would make this proposal.

“Take a rest?” replied Paganel; “how? where? we have no shelter.”

“It is indispensable, if only for Robert.”

“No, my lord,” replied the courageous child; “I can still walk—do not stop.”

“We will carry you, my boy,” said Paganel, “but we must, at all hazards, reach the eastern slope. There, perhaps, we shall find some hut in which we can take refuge. I ask for two hours more of travel.”

“Do you all agree?” asked Glenarvan.

“Yes,” replied his companions.

“I will take charge of the brave boy,” added the equally brave Mulready.

They resumed their march towards the east. Two hours more of terrible exertion followed. They kept ascending, in order to reach the highest summit of this part of the mountain.

Whatever were the desires of these courageous men, the moment now came when the most valiant failed, and dizziness, that terrible malady of the mountains, exhausted not only their physical strength but their moral courage. It is impossible to struggle with impunity against fatigues of this kind. Soon falls became frequent, and those who fell could only advance by dragging themselves on their knees.

Exhaustion was about to put an end to this too prolonged ascent; and Glenarvan was considering with terror the extent of the snow, the cold which in this fatal region was so much to be dreaded, the shadows that were deepening on the solitary peaks, and the absence of a shelter for the night, when the major stopped him, and, in a calm tone, said,—

“A hut!”