CHAPTER I. - II.

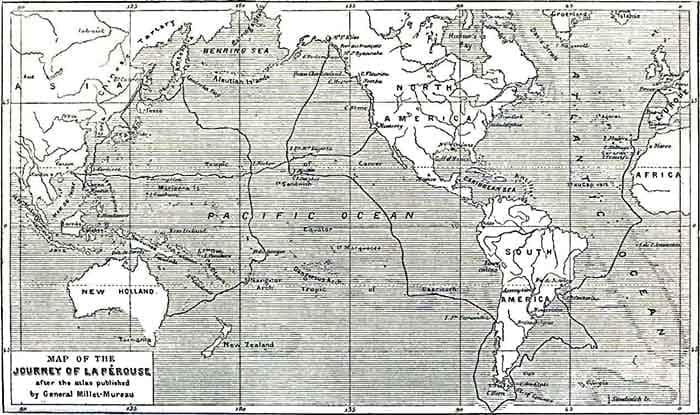

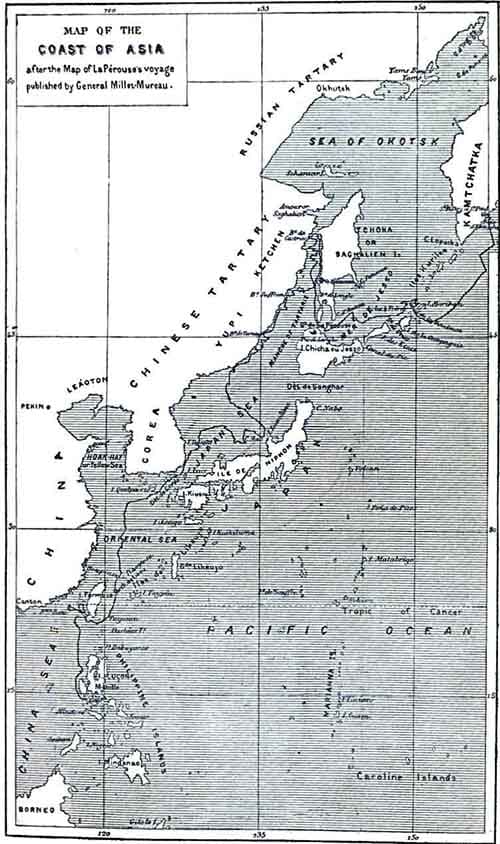

The Expedition of La Perouse—St. Catherine's Island—Conception Island—The Sandwich Islands—Survey of the American coast—French Port—Loss of two boats—Monterey and the Indians of California—Stay at Macao—Cavite and Manilla—En route for China and Japan—Formosa—Quelpaert Island—The coast of Tartary—Ternay Bay—The Tartars of Saghalien—The Orotchys—Straits of La Perouse—Ball at Kamtchatka—Navigator Islands—Massacre of M. de Langle and several of his companions—Botany Bay—No news of the Expedition—D'Entrecasteaux sent in search of La Perouse—False News—D'Entrecasteaux Channel—The coast of New Caledonia—Land of the Arsacides—The natives of Bouka—Stay in Port Carteret—Admiralty Islands—Stay at Amboine—Lewin Land—Nuyts Archipelago—Stay in Tasmania—Fête in the Friendly Islands—Particulars of the stay of La Perouse at Tonga Tabou—Stay at Balado—Traces of La Perouse in New Caledonia—Vanikoro—Sad fate of the Expedition.

The result of Cook’s voyage, except the fact of his death, was still unknown, when the French government resolved to make use of the leisure which the peace just concluded had secured to the navy. The French officers, desirous of emulating the success of their old rivals the English, were fired with a noble emulation to excel them in some new field. The question arose as to the fittest person for the conduct of an important expedition. There was no lack of deserving candidates. Indeed, in the number lay the difficulty.

The Minister’s choice fell upon Jean François Galaup de la Perouse, whose important military services had rapidly advanced him to the rank of captain. During the last war he had been intrusted with the difficult mission of destroying the English posts in Hudson’s Bay, and in this task he had proved himself not only an able soldier and sailor, but a man who could combine humanity with professional firmness. Second to him in the command was M. de Langle, who had ably assisted him in the expedition to Hudson’s Bay.

(Fac-simile of early engraving.)

A large staff embarked upon the two frigates La Boussole and L’Astrolabe. On board the Boussole were La Perouse; Clenard, who was made captain during the expedition; Monneron, an engineer; Bernizet, a geographer; Rollin, a surgeon; Lepante Dagelet, an astronomer of the Academy of Sciences; Lamanon, a physicist; Duché de Vancy and Prevost the younger, draughtsmen; Collignon, a botanist; and Guéry, a clock maker. The Astrolabe, in addition to her commander, Captain de Langle, carried Lieutenant de Monte, who was made captain during the voyage, and the celebrated Monge, who, fortunately for the interests of science, landed at Teneriffe upon the 30th of August, 1785.

The Academy of Sciences and the Society of Medicine had drawn up reports for the Minister of Marine, in which they called the attention of the navigators to certain points. Lastly, Fleurien, the superintendent of ports and naval arsenals, had himself drawn up the maps for the service of the expedition, and added to it an entire volume of learned notes and discussions upon the results of all known voyages since the time of Christopher Columbus.

The two ships carried an enormous amount of merchandise for trade, as well as a vast quantity of provisions and stores, a twenty-ton boat, two sloops, masts, and reserve sets of sails and rigging.

The two frigates sailed upon the 1st of August, 1785, and anchored off Madeira thirteen days later.

The French were at once charmed and surprised at the kind and cordial welcome accorded them by the English residents. Upon the 19th La Perouse put into Teneriffe.

“The various observations,” he says, “made by MM. de Fleurien, Verdun, and Borda, upon Madeira, the Salvage Islands, and Teneriffe leave nothing to be wished for. Our attention was therefore confined to testing our instruments.”

This remark proves that La Perouse was capable of doing justice to his predecessors. And we shall have other opportunities of observing that quality in him.

While the astronomers devoted themselves to estimating the regularity of the astronomical watches, the naturalists, with several officers, ascended the Peak, and collected some curious plants. Monneron succeeded in measuring this mountain with much greater accuracy than his predecessors, Herberdeen, Feuillée, Bouguer, Verdun, and Borda, who calculated its height respectively at 2409, 2213, 2100, and 1904 fathoms. Unfortunately his work, which would have settled the discussion, never reached France.

Upon the 16th of October, the isles, or rather rocks, of Marten Vas were seen. La Perouse ascertained their position, and afterwards made for the nearest, Trinity Island, which was only some nine leagues to the west. The commander of the expedition sent a sloop on shore in charge of an officer, in the hope of finding water, wood, and provisions. The officer had an interview with the Portuguese governor, whose garrison consisted of about two hundred men, fifteen of whom wore uniforms, and the rest merely shirts. The poverty of the land was obvious, and the French re-embarked without having obtained anything.

After a vain search for Ascension Island, the expedition reached Saint Catherine’s Island, off the coast of Brazil.

“After ninety-six days’ navigation,” we read in the narrative of the voyage published by General Millet-Mureau, “we had not one case of illness on board. The health of the crew had remained unimpaired by change of climate, rain, and fog; but our provisions were of first-class quality; I neglected none of the precautions which experience and prudence suggested to me; and above all, we kept up our spirits by encouraging dancing every evening among the crew, whenever the weather permitted, from eight o’clock till ten.”

Saint Catherine’s Island, of which we have more than once had occasion to speak in the course of this narrative, extends from 27° 19′ 10″ S. lat. to 27° 49′. It is only two leagues wide, and is divided in its narrowest part from the mainland by a channel of two hundred fathoms. The town of Nostra Señora del Desterra, the capital of the colony, where the governor resides, is built at the point of this narrow entrance. The population amounts, at the utmost, to three thousand, and there are about four hundred houses. The appearance of the town is very pleasant. According to Frezier’s account, this island was a refuge in 1712 for the vagabonds who fled there from different parts of Brazil. They were Portuguese subjects in name only, and recognized no other authority. The country is so fertile that the inhabitants can live quite independently of any neighbouring colony. The ships in the harbour gave them shirts and coats, of which they had absolutely none, in exchange for provisions.

This island is extremely fertile, and the soil could easily be made to grow sugar-cane, but the inhabitants are so poor that they cannot buy the needful slaves for the labour.

The French vessels found all that they needed in this spot, and their officers were cordially received by the Portuguese authorities.

The following fact will give an idea of the hospitality of these people. “My boat,” says La Perouse, “having been upset in a creek where I was having wood cut, the inhabitants, after assisting in saving it, insisted on our shipwrecked sailors using their beds, and themselves slept on mats upon the floor of the room where they received them so hospitably. A few days later they brought to my vessel the sails, mast, grapnel, and flag of the boat, which would have been of great use to them for their pirogues.”

The Boussole and the Astrolabe weighed anchor upon the 19th of November, and directed their course to Cape Horn. After a violent storm, during which the frigates behaved very well, and after forty days’ fruitless search for the large island discovered by a Frenchman, Antoine de la Roche, and called Georgia by Captain Cook, La Perouse crossed the Straits of Lemaire. Finding the winds favourable, he decided not to remain in Good Success Bay at this advanced season of the year, but immediately to double Cape Horn, in the hope of avoiding a possible delay that would have exposed his ships to injury and his crew to useless fatigue.

The friendly demonstrations of the Fuegians, the abundance of whales, which had never before been disturbed, the immense flocks of albatross and petrels, did not change his resolve. Cape Horn was rounded more easily than could have been expected. Upon the 9th of February the expedition was in the Straits of Magellan, and upon the 24th anchor was cast in Concepcion Harbour, which La Perouse preferred to that of Juan Fernandez, on account of the exhaustion of his provisions. The robust health of the crews astonished the Spanish governor. Possibly this was the first time a vessel had rounded Cape Horn and arrived in Chili without any sick on board.

The town, which was destroyed by an earthquake in 1757, had been rebuilt three leagues from the sea, upon the shore of the river Biobio. The houses are of one storey, and the town of La Concepcion contains ten thousand inhabitants. The bay is one of the most commodious in the world; the sea is smooth, and almost free from currents. This part of Chili is wonderfully fertile. One ear of corn reproduces sixty; vines are equally prolific; and the country teems with innumerable flocks, which multiply beyond all credence.

In spite of these prosperous conditions the country made no progress, on account of the prohibitive system which at this time prevailed. Chili, with its productions, which might easily have fed the half of Europe; its wool, which might have sufficed for the manufactures of France and England; its meats, which might have been preserved—had no commerce whatever. At the same time the duty upon imported goods was excessive, so that living was very dear. The middle class, as the “bourgeoisie” are now called, did not exist; the population consisted of two classes, the rich and the poor, as the following passage shows:—

“The dress of the women consists of a plaited skirt of the ancient gold or silver tissues which were formerly manufactured at Lyons. These petticoats, which are kept for grand occasions, are often inherited like diamonds, and are handed down from generation to generation. They are only worn by a small number of the higher class; the others have scarcely the means of clothing themselves at all.”

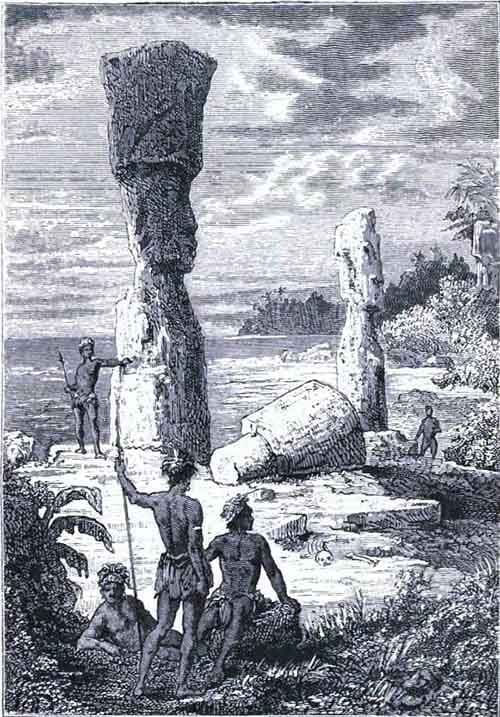

We will not follow La Perouse into his details of the enthusiastic reception given to him, and we will pass over in silence his description of balls and toilettes, which never for a moment induced him to lose sight of the object of his voyage. So far the expedition had only passed through regions often before visited by Europeans. It was now about to penetrate to less-known realms. Anchor was raised upon the 15th of March, and, after a voyage entirely free from incident, the two frigates anchored upon the 9th of April in Cook’s Bay, Easter Island.

La Perouse affirms that Mr. Hodges, the painter, who accompanied the celebrated English navigator, has given a very unjust representation of the inhabitants. Generally their physiognomies are pleasing, but they cannot be said to have much character.

This is by no means the only point upon which the French navigator differs from Captain Cook. He believed the famous statues, of which one of the draughtsmen made an excellent sketch, to have been the work of the present generation, whose numbers he estimates at two thousand. It appeared to him also that the absolute lack of trees, and therefore of lakes and rivers, was due to the extravagant waste of wood by the earlier races. No disagreeable incident occurred during the stay. Robberies, it is true, were frequent; but as the French intended remaining only one day on the island, they thought it superfluous to give the population stricter ideas of honesty.

After leaving Easter Island, upon the 10th of April, La Perouse followed much the same route as Cook had done in 1777, when he sailed from Tahiti to the American coast; but he was a hundred leagues farther west. La Perouse indulged in the hope of making discoveries in this little-known region of the Pacific Ocean, and he promised to reward the sailor who should first sight land. Upon the 29th of May the Hawaian archipelago was reached.

The naval watches proved of great assistance upon this occasion, and justified the opinion entertained of them. Upon reaching the Sandwich Islands La Perouse found a difference of five degrees between the longitude given and that obtained by him. Without the watches he would have placed this group five degrees too far east. This explains why the islands discovered by the Spanish—Mendana, Queros, &c.—are much too near the American coast, and also the non-existence of the group called by the Spaniards La Mesa, Los Majos, and La Disgraceada, which there is every reason to suppose was none other than the Sandwich archipelago, as Mesa in Spanish means “table,” and Captain King compares the mountain called Mauna Loa to a plateau or table-land. He did not, however, trust to conjecture; he crossed the reputed site of Los Majos, and found not the slightest trace of land.

“The aspect of Monee,” says La Perouse, “is delightful. We saw water tumbling in cascades from the summit of the mountains, and reaching the sea after watering the Indian plantations, of which there are so many that each village extends over three or four leagues. All the huts are, however, on the sea-shore; and the mountains are so close that the habitable portion of the land appeared to me to be less than half a league in depth. One must be a sailor, and, like us, have been reduced to a bottle of water per day in a burning climate, to realize the sensations we experienced. The trees which crowned the mountains, the green fields, the banana-trees which surrounded the dwellings, all combined to charm our senses with an inexpressible delight; but the sea broke violently on the shore, and, like Tantalus, we were obliged to devour with our eyes what was completely beyond our reach.”

The two frigates had no sooner anchored than they were surrounded by pirogues, full of natives, offering pigs, potatoes, bananas, “taro,” &c. Clever traders, they attached most value to bits of old iron rings. Their acquaintance with iron and its use, for which they were not indebted to Cook, is another proof that this people had known the Spaniards, to whom the discovery of the group is probably due.

The welcome accorded to La Perouse was most cordial, in spite of the military force by which he had thought proper to protect himself. Although the French were the first to land on Monee Island, La Perouse did not think it his duty to take possession.

“The usual European custom in such matters,” he says, “is perfectly ridiculous. Philosophers may well sigh when they see men, simply because they have guns and bayonets, thinking nothing of sixty thousand of their fellow-men, and, without the least respect for the most sacred rights, looking upon a land whose inhabitants have cultivated it in the sweat of the brow, and whose ancestors lie buried there, as an object fit for conquest.”

La Perouse does not pause to give any details about the inhabitants of the Sandwich Islands. He only passed a few hours there, whilst the English remained for four months. He therefore rightly refers to Captain Cook’s narrative.

During their short stay the French bought more than a hundred pigs, mats, fruits, a pirogue, ornaments made of feathers and shells, and handsome helmets decorated with feathers.

The instructions furnished La Perouse before his departure enjoined him to survey the American coast, of which a portion, extending to Mount Elias had, with the exception of Nootka port, been merely sighted by Captain Cook.

On the 23rd of June he reached 60° N. lat., and, in the midst of a long chain of snow-covered mountains, recognized the Mount Elias of Behring. After skirting along the coast for some time, La Perouse sent three boats, under command of one of his officers, M. de Monte, who discovered a large bay, to which he gave his name.

Following the coast at a short distance, surveys were taken, which were uninterrupted as far as an important river, which received the name of Behring. Apparently it was that to which Cook had given this name.

Upon the 2nd of July, in 58° 36′ lat., and 140° 3′ long., what appeared to be a fine bay was discovered. Boats, under command of MM. de Pierrevert, de Flassan, and Boutevilliers, were sent to examine it.

Their report being favourable, the two frigates arrived at the entrance of the bay, but the Astrolabe was driven back to the open sea by a strong current, and the Boussole was forced to join her. At six o’clock in the morning, after a night passed under sail, the vessels again approached the bay. “But,” says the narrative, “at seven in the morning, when we were close to it, the wind veered so suddenly to W.N.W. and N.N.W., that we were forced to give way, and even to bring our ships to the wind. Fortunately the tide carried our frigates into the bay, and we escaped the rocks on the east by half a pistol’s range. I anchored in three and a half fathoms, with a rocky bottom, half a cable’s length from shore. The Astrolabe had anchored in the same depth, and upon a similar bottom. In all the thirty years I have spent at sea, I have never seen two vessels in greater danger. Our situation would have been safe had we not anchored upon a rocky bottom, which extended several cables’ length around us, and which was different from what MM. de Flasson and Boutevilliers had reported. We had no time to make reflections; it was above everything necessary to get out of our dangerous anchorage, to which the rapidity of the current was a great obstacle.” However, by dint of much skilful tacking, La Perouse succeeded.

Ever since their entry into the bay the vessels had been surrounded by pirogues swarming with savages. The natives showed a decided preference for iron, in exchange for fish and the skins of otters and other animals. After a few days’ stay their number increased rapidly, and they became, if not dangerous, at least a nuisance.

La Perouse established an observatory upon one of the islands in the bay, and set up tents for the sail makers and smiths. Although these posts were most carefully watched, the natives, gliding along the ground like snakes, scarcely stirring a leaf, managed in spite of our sentinels to commit various thefts; and one night they were clever enough to enter the tent where MM. de Launston and Darbaud (who were in charge of the observatory) slept. They carried off a silver-mounted gun, as well as the clothes belonging to the two officers, who had placed them for safety under their pillows. They escaped the notice of a guard of twelve men, and the two officers were not even awakened.

But now the stay of the expedition in this port drew to a close. The soundings, surveys, plans, and astronomical observations were completed; but, before finally leaving the island, La Perouse wished thoroughly to explore the depths of the bay. He imagined that some large river must empty itself into it, which would enable him to penetrate into the interior; but in all the openings he entered he found only vast glaciers, which extended to the very summit of Fair Weather Mount.

No accident or sickness marred the success which had so far attended the expedition.

“We thought ourselves,” says La Perouse, “the most fortunate of navigators, for having reached so great a distance from Europe without having had one invalid or a single sufferer from scurvy. But the greatest misfortune, and one it was impossible to foresee, now awaited us.”

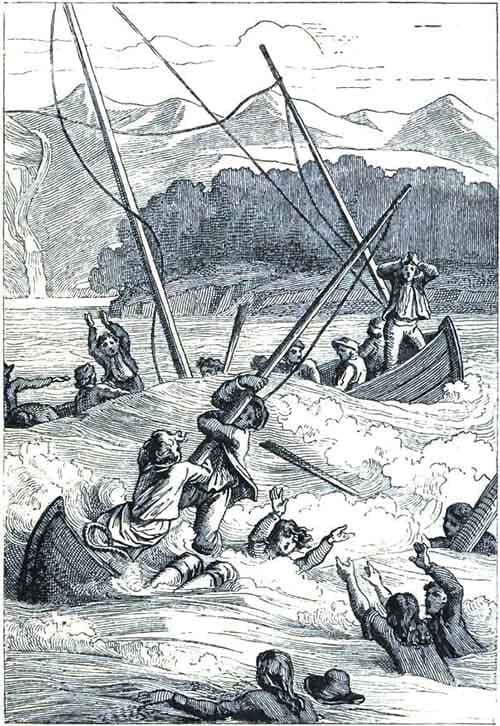

Upon the chart of the Port des Français, drawn up by MM. Monneron and Bernizet, the soundings alone remained to be indicated. The naval officers were bound to accomplish the task, and three boats, under the orders of MM. d’Escures, de Marchainville, and Boutin, were selected for the undertaking. La Perouse, acquainted with the somewhat rash zeal of M. d’Escures, advised him on the eve of departure to act with most careful prudence, and only to attempt the soundings in the channel if the sea were smooth.

The boats left at six o’clock in the morning. It was as much a party of pleasure as of duty, as the crews were to hunt, and breakfast under the trees.

“At ten in the morning,” says La Perouse, “I saw our little boat return. Somewhat surprised, for I had not expected it so soon, I asked M. Boutin, before he came on deck, whether he had any news. At first I feared an attack from the natives, and M. Boutin’s expression was not calculated to reassure me, for it was profoundly sad.

“He soon related to me the terrible disaster he had just witnessed, and from which he had escaped by the presence of mind which enabled him to see the best course to pursue in the dreadful peril. Carried, whilst following his commander, into the midst of breakers caused by the tide rushing with a speed of three or four leagues per hour out of the channel, he thought he could place his boat stern on the breakers; the boat yielding to their force, and being impelled by the tide, would not fill, but would be carried safely outside.

“Soon, however, he saw breakers ahead of his boat, and found himself in the open sea. More concerned for the safety of his companions than for his own, he again approached the breakers, and in the hope of saving some life he again braved them, but was repulsed by the tide; finally, he mounted on M. Mouton’s shoulder, in the hope of finding a wider opening. All was in vain; everything had been swallowed up, and M. Boutin returned with the ebb of the tide.

“The sea becoming quieter, this officer had still some hope of finding the boat of the Astrolabe; he had only witnessed the loss of ours. M. de Marchainville was now a quarter of a mile from the danger, that is to say, in a sea as still as the quietest harbour; but, impelled by an imprudent generosity—for all help was quite impossible under the circumstances—this rash young officer, being too high-spirited and too courageous to pause in presence of his friends’ danger, flew to their help, threw himself among the breakers, and, a victim to his imprudence and disregard of his chief’s orders, perished with him.

“M. de Langle shortly after came on board my ship, as much overcome as myself, and informed me with tears that the misfortune was even greater than I had supposed. We had always made a point, ever since leaving France, of never allowing the two brothers, M. la Borde Marchainville and M. la Borde Boutevilliers, to go on the same service, but on this one occasion he had yielded, as they desired to hunt together; and it was almost wholly on this account that we had, both of us, directed our boats in the way we did, thinking there was as little danger as there is in Brest Harbour in fine weather.

“Several boats were at once despatched in search of the shipwrecked crew. Rewards were offered to the natives if they saved any one; but the return of the sloops destroyed all hope. All had perished.”

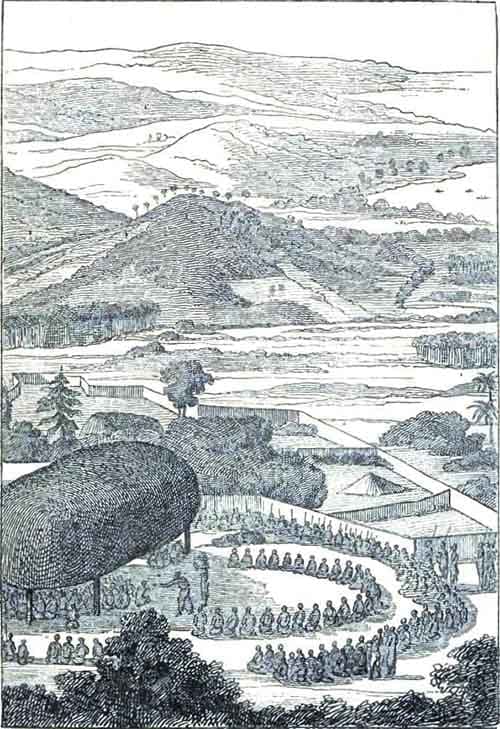

(Fac-simile of early engraving.)

Eighteen days after this catastrophe, the two frigates left the Port des Français. La Perouse erected a monument to the memory of his unfortunate countrymen, in the middle of the bay, on an island which he called the Cenotaph. It bore the following inscription:—

“At the entrance of this port, twenty-one brave sailors perished.

Whoever you are, mingle your tears with ours.”

A bottle, containing an account of this deplorable accident, was buried at the foot of the monument.

The Port des Français, which is situated in 58° 37′ N. lat., and 139° 50′ W. long., presents many advantages, but also many inconveniences—foremost amongst them the currents of the channel. The climate is much milder than in Hudson’s Bay, which is in the same latitude. The vegetation is vigorous; pines six feet in girth, and a hundred and forty in height, are not rare. Celery, sorrel, lupine, wild pea, chicory, and mimulus are met with in every direction, as well as many pot-herbs, the use of which helped to keep the crews in health.

The sea supplied abundance of salmon, trout, cod, and plaice.

In the woods are found black and brown bears, the lynx, ermine, weasel, minever, squirrel, marmot, beaver, fox, elk, and the wild goat. The most precious skins are those of the otter, wolf, and sea-bear.

“But if the vegetable and animal productions of this country,” says La Perouse, “are similar to those of many others, its aspect cannot be compared with them, and I doubt whether the deep valleys of the Alps and Pyrenees offer so terrible, and at the same time so picturesque, a prospect. Were it not at one of the extremities of the world, it should be visited by every one.”

As to the inhabitants, La Perouse gives an account of them which is worth preserving.

“The Indians in their pirogues surrounded our frigates, hovering about for three or four hours before beginning to exchange a few fish, or two or three otter skins; they seized every opportunity of robbing us; they tore off all the iron which could be easily carried away, and they took every precaution to elude our vigilance at night. I invited some of the principal personages on board my frigate, and loaded them with presents; and the very men I distinguished in this manner did not scruple to steal a nail or an old pair of trousers. Whenever they assumed a particularly lively and pleasant air, I was convinced that they had committed a theft, and I often pretended not to see it.”

The women make an opening in the thick part of the lower lip, the whole length of the jaw. They wear a sort of wooden bowl without a handle, which rests on the gums, “to which this split lip forms an outer cushion, in such a way that the lower part of the mouth protrudes some two or three inches.”

The forced stay which La Perouse had just made in Port des Français prevented his stopping elsewhere and reconnoitring the indentations of the coast, for at all hazards he was to reach China during the month of February, in order to secure the following summer for the survey of the coast of Tartary.

He successively reconnoitred, upon this coast, Cross Sound, where the high snow-covered mountains cease, Cook’s Island Bay, Engamio Cape, low land partly submerged and containing Mount Hyacinthine, Mount Edgecomb of Cook, Norfolk Sound, where the following year the English navigator Dixon was to anchor, ports Necker and Guibert, Cape Tschiri-Kow, Croyère Islands, so called after the brother of the famous geographer Delisle, companion of Tschiri-Kow, the San Carlos Islands, La Touche Bay, and Cape Hector.

La Perouse imagined that these various coast lines were formed by a vast archipelago; and in this he was correct. They contained George III.’s Island, Prince of Wales and Queen Charlotte’s Islands—Cape Hector forming the southern extremity of the latter.

The season was far advanced, and too short a time remained at La Perouse’s disposal to allow of his making detailed observations of these countries; but his instinct had justly led him to imagine that the series of points he had discovered indicated a group of islands, and not a continent. Beyond Cape Fleurien, which formed the extremity of an elevated island, he passed several groups, which he named Sartines, and then returning, he reached Nootka Sound on the 25th of August. He afterwards visited various parts of the continent which Cook had been unable to approach, and which had left a blank on his chart. This navigation was attended with a certain amount of danger, on account of the currents, “which rendered it impossible to make more than three knots an hour at a distance of five leagues from land.”

Upon the 5th of September new islets were discovered, about a league from Cape Blanco, to which the captain gave the name of Necker Islands. The fog was very thick, and more than once the fear of running upon some islet or rock, the existence of which could not be suspected, obliged the vessels to deviate from the land. Until they reached Monterey Bay the weather continued bad. At that port La Perouse found two Spanish vessels.

At this time Monterey Bay abounded in whales, and the sea was literally covered with pelicans, which were very common upon the Californian coast.

A garrison of two hundred and eighty men was sufficient to keep in order a population of fifty thousand Indians, wandering about this part of America. It must be admitted that these Indians were usually small and insignificant, and not endowed with that love of independence which characterizes the northern tribes; and, unlike them, they have no appreciation of art, and no industry.

“These Indians,” says the narrative, “are very expert in the use of the bow and arrow. They killed the smallest birds in our presence. It is true that they approach them with wonderful patience, hiding themselves, gliding, somehow, close to their prey, and aiming at them only when within fifteen paces.

“Their skill in the capture of larger animals is even more wonderful. We saw an Indian with a stag’s head over his own, walking on all fours, appearing to graze, and carrying out the pantomime with such truth to life that our hunters would have fired at him at thirty paces had they not been prevented. By this means the natives approach quite close to a herd of deer, and then kill them with arrows.”

La Perouse gave many details of the presidency of Loretto and of the Californian missions, but these are rather of historical interest, and are out of place in a work of this kind. His remarks upon the fertility of the country are more within our programme. “The harvest of maize, barley, corn, and peas,” he says, “is comparable only to that of Chili. Our European husbandmen could not conceive of such abundance. The most moderate yield of corn is at the rate of from seventy and eighty to one, and the largest from sixty to a hundred.”

Upon the 22nd of September the two frigates returned to sea, after a cordial welcome from the Spanish governor and the missionaries. They carried with them a quantity of provisions of all sorts, which would be of the greatest value to them during the long trip to be taken before reaching Macao.

The portion of the ocean now to be crossed by the French was almost unknown. The Spaniards had navigated it previously, but their political jealousy prevented their publishing the discoveries and observations they had made. La Perouse wished to steer S.W. as far as 28° lat., where some geographers had placed the island of Nuestra Señora-de-la-Gorta.

But he looked for it in vain during a long and difficult cruise, with contrary winds, which sorely tried the patience of the navigators.

“We were daily reminded,” he says, “by the condition of our sails and rigging, that we had been sixteen months at sea. Our ropes gave way, and the sail makers could not repair the sails, which were fairly worn out.”

Upon the 6th of November a small island, or rather rock, some five hundred fathoms long, upon which not a single tree grew, and which was thickly covered with guano, was discovered. It was named Necker Island, and is in 166° 52′ long. W. of Paris, and 23° 34′ N. lat.

Never had the expedition seen a more lovely sea, or a more exquisite night, when suddenly, at about half-past one in the morning, breakers were perceived two cable lengths ahead of the Boussole. The sea, only broken here and there by a slight ripple, was so calm that it scarcely made any sound. The ship’s course was altered immediately; but the manoeuvre took time, and when it was accomplished the vessel was but a cable’s length off the rocks.

“We had just escaped one of the most imminent dangers to which navigators are subject,” says La Perouse, “and I must do my crews the justice to say that less disorder and confusion in such a position would have been impossible. The slightest neglect in the execution of the manoeuvres which were necessary to carry us from the breakers would have been fatal.”

These rocks were unknown; it was therefore needful to determine their exact position, for the safety of succeeding navigators. La Perouse, after fulfilling this duty, named them the “Reef of the French Frigates.”

Upon the 14th of December the Astrolabe and the Boussole sighted the Mariana Islands. A landing was effected upon the volcanic island of Assumption. Here the lava had formed ravines and precipices, bordered by a few stunted cocoa-nut trees, alternately with tropical creepers and a few shrubs. It was almost impossible to advance a couple of hundred yards in an hour. Landing and re-embarkation were difficult, and the few cocoa-nut shells and bananas, of a new variety, which the naturalists obtained, were not worth the risk.

It was impossible to remain longer in this archipelago if China were to be reached before the vessels returned to Europe. They were to take back an account of the results of the expedition upon the American coast, and of the crossing to Macao.

After taking the position of the Bashees, without stopping, La Perouse sighted the coast of China, and next day cast anchor in the roadstead of Macao.

Here La Perouse met with a small French cutter, commanded by M. de Richery, midshipman, whose business it was to cruise about the eastern coast, and protect French trade.

The town of Macao is so well known that it is needless for us to give La Perouse’s description of it. The constant outrages and humiliations to which Europeans were daily subjected under the most despotic and cowardly government in the world, aroused the indignation of the French captain, and made him heartily wish that an international expedition might put a stop to so intolerable a state of things.

The furs which had been collected upon the American coasts were sold at Macao for ten thousand piastres. The sum produced should have been divided among the crews, and the head of the Swedish company undertook to ship it at Mauritius; but the unfortunate sailors themselves were never to receive the money.

Leaving Macao on the 5th of February, the vessels directed their course to Manilla, and, after sighting the shoals of Pratas, Bulinao, Manseloq, and Marivelle, wrongly placed upon D’Après’ maps, they were forced to put into the port of Marivelle, to wait for better winds and more favourable currents. Although Marivelle is only one league to windward of Cavito, three days were consumed in reaching the latter port.

“We found,” says the narrative, “different houses where we could repair our sails, salt our provisions, construct two boats, lodge the naturalists and geographical engineers, and the governor kindly lent us his own for the establishment of our observatory. We enjoyed as much liberty as if we had been in the country; and in the market and arsenal we found the same resources as in the best European ports.”

Cavito, the second town of the Philippine islands, and the capital of the province of the same name, was then but a miserable village, where only Spanish military and government officers resided; but although the town was nothing but a mass of ruins, it was none the less a port, and afforded the French every possible resource. Upon the morrow of his arrival La Perouse, accompanied by De Langle and his principal officers, paid a visit to the governor, reaching Manila by boat.

“The environs of Manila are delightful,” he says. “A most beautiful river flows through it, separating into different canals, one of which leads to the famous Bay Lake, which is distant seven leagues in the interior, surrounded by more than a hundred Indian settlements in the midst of a most fertile territory.

“Manila, built upon the shore of the bay of that name, which is more than twenty-five leagues in circumference, is at the mouth of a river navigable as far as the lake in which it rises. It is probably the most fortunately situated town in the whole world. Provisions are found there in the greatest profusion, and very cheap; but clothing, European cutlery, and furniture fetch an enormous price.

“Want of competition, the prohibitive tariffs, and commercial restrictions of every sort, tend to make the productions and manufactured goods of India and China at least as dear as in Europe; and although the various duties on imports bring to the treasury some eight hundred thousand piastres, the colony costs the Spanish government at least fifteen hundred thousand francs per annum, which are sent from Mexico. The immense possessions of the Spanish in America have prevented the government from bestowing much attention upon the Philippines. They are still like the possessions of great lords, which remain uncultivated, though they might provide fortunes for many families.

“I do not hesitate to state, that a great nation with no colony but the Philippine Islands, supposing that colony to be as well governed as possible, need not envy all the European colonies in Africa and America.”

Upon the 9th of April—after having heard of the arrival at Macao of M. d’Entrecasteaux, who had come from Mauritius with the contrary monsoon, and received despatches from Europe by the frigate La Subtile, MM. Guyet, midshipman, and Le Gobien, naval officer, and a reinforcement of eight sailors—the two vessels set out for the coast of China.

Upon the 21st La Perouse sighted Formosa, and at once entered the channel which separates that island from China. He discovered a very dangerous bank unknown to navigators, and carefully examined the soundings and approaches. Shortly afterwards he passed in front of the bay of the ancient Dutch fort of Zealand, where the capital of the island, Tai-wan, is situated.

The monsoon was unfavourable for ascending the channel, and La Perouse therefore resolved to pass to the east of the island. He rectified the position of the Pescadores Islands, a mass of rocks which assume various shapes, reconnoitred the small island of Botol-Tabaco-Xima, where no navigator had landed, coasted Kinin Island, which forms part of the kingdom of Liken, whose inhabitants are neither Chinese nor Japanese, but appear to be of both races, and sighted Hoa-pinsu and Tiaoy-su Islands. The latter form part of the Liken Archipelago, known only through the letters of Father Goubil, a Jesuit.

The frigates then entered the Eastern Sea, and directed their course to the channel which divides China and Japan. La Perouse there encountered fogs as thick as those which prevail upon the coast of Labrador, with variable and violent currents. The first point of interest before entering the Sea of Japan was Quelpaert Island, first made known to Europeans by the shipwreck of the Sparrow Hawk upon its coast in 1635. La Perouse determined its southerly extremity, and surveyed it for a distance of twelve leagues.

“It is scarcely possible,” he says, “to find an island of pleasanter aspect. A peak of about four thousand five hundred feet high, visible at a distance of eighteen or twenty leagues, rises in the centre of the island; the land slopes gently from thence to the sea, so that the houses look like an amphitheatre. The soil seemed to be highly cultivated. By the aid of our glasses we clearly made out the divisions of the fields. They are in very small allotments, which augurs a large population. The different shades of the various cultivated patches give a very agreeable variety to the view.”

The explorers had ample opportunity for taking the longitude and latitude, which was the more important, as no European vessel had navigated these seas, which were only indicated upon the maps in accordance with the Chinese and Japanese maps published by the Jesuits.

Upon the 25th of May the frigates entered the channel of Corea, which was minutely explored, and in which soundings were taken every half hour.

As it was possible to keep close in shore, it was easy to observe some fortifications in the European style, and to note all their details.

On the 27th an island was perceived which was not to be found upon any map, and which seemed to be about twenty leagues distant from the coast of Corea. It received the name of Dagelet Island.

The course was now directed towards Japan, but it was very slow, on account of the contrary winds that prevailed.

On the 6th of June Cape Noto and the island of Tsus Sima were discovered.

“Cape Noto, upon the Japanese coast,” says La Perouse, “is a point on which geographers may rely. Reckoning from it to Cape Kona on the eastern coast, the position of which was determined by Captain King, the width of the northern half of the empire may be ascertained. Our observations have the greater value for geographers as they determine the width of the Gulf of Tartary, to which I now directed my course.”

Upon the 11th of June La Perouse sighted Tartary. He made land precisely at the boundary between the Corea and Manchuria. The mountains appeared to be six or seven thousand feet high. A small quantity of snow was visible on the summits. No trace of inhabitants or cultivation could be seen; nor was any river’s mouth found upon a length of coast extending for forty leagues. A halt would have been desirable, to enable the naturalists and lithologists to make observations.

“Up to the 14th of June the coast had run to the N.E. by N. We were now in 44° lat., and had reached the degree which geographers assign for the so-called Strait of Tessoy, but we were five degrees farther west than the longitude given for this spot. These five degrees should be taken from Tartary, and added to the channel which separates it from the islands north of Japan.”

Whilst coasting along this shore no sign of habitation had been perceived—not a pirogue left the shore. The country, although covered with magnificent trees and luxuriant vegetation, appeared to be uninhabited.

On the 23rd of June the Boussole and the Astrolabe cast anchor in a bay situated in 45° 13′ N. lat. and 135° 9′ E. long. It was named Ternay Bay.

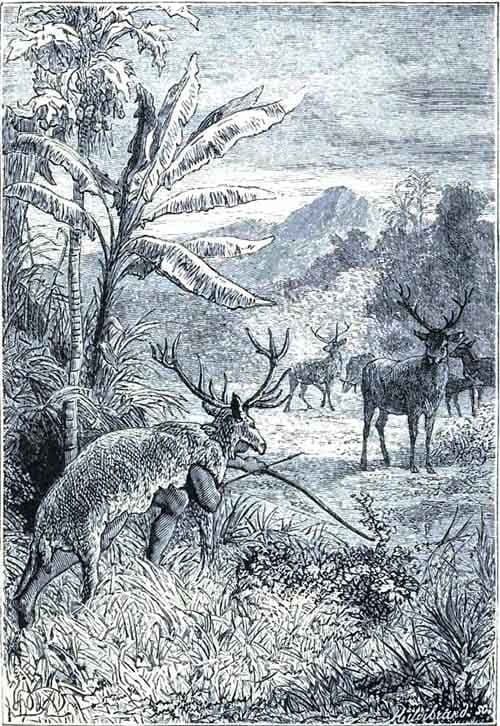

“We burned with impatience,” say La Perouse, “to reconnoitre this land, which had occupied our imagination ever since we left France. It was the only portion of the globe which had escaped the indefatigable activity of Captain Cook; and perhaps we owe the small advantage of having first landed there to the sad event which ended his days.

“This roadstead was formed of five little creeks, separated one from the other by hillocks covered with trees of a more delicate and varied green than is to be seen in France in the brightest spring. Before our boats reached the shore, our glasses had been directed to the coast, but we perceived nothing but stags and bears, quietly grazing. Our impatience to disembark increased at the sight. The ground was carpeted with plants similar to those of our climate, but more vigorous and green; most of them were in flower. At every step we found roses, red and yellow lilies, lilies of the valley, and almost all our field flowers. The summits of the mountains were crowned with pines, and oak-trees grew half way up, decreasing in size and vigour as they neared the sea. The rivers and streams were planted with willows, birches, and maples; and skirting the larger woods we saw apple-trees and azaroles in full bloom, as well as clumps of nut-trees, the fruit of which was beginning to form.”

Upon returning from a fishing excursion the French met with a Tartar tomb. Curiosity induced them to open it, and they found in it two skeletons, lying side by side. The heads were covered with stuff caps, the bodies were wrapped in bearskins, and from the waists hung several little Chinese coins and copper ornaments. They also found half-a-score of silver bracelets, an iron hatchet, a knife, and other things, amongst which was a small bag of blue nankeen filled with rice.

Upon the morning of the 27th La Perouse left this solitary bay, after depositing there several medals, with an inscription giving the date of his arrival.

A little further on, more than eight hundred cod, which were at once salted, were caught, and an immense quantity of oysters with superb mother of pearl were also obtained.

After a stay in Saffren Bay, situated in 47° 51′ N. lat. and 137° 25′ E. long., La Perouse discovered, upon the 6th of July, an island, which was no other than Saghalien. The shore here was as wooded as that of Tartary. Lofty mountains arose in the interior, the highest of which was called Lamanon peak. As huts and smoke were seen, M. de Langle and several officers landed. The inhabitants had recently fled, for the ashes of their fires were scarcely cold.

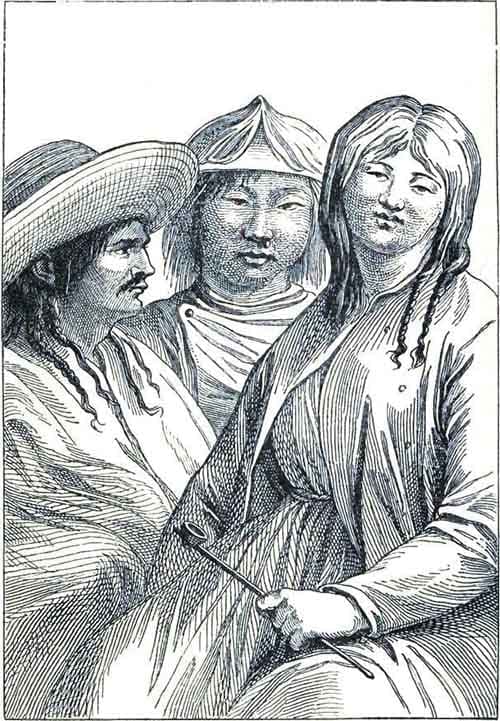

Just as the French were re-embarking, after leaving some presents for the natives, a pirogue landed seven natives, who showed no signs of fear.

“Amongst them,” says the narrative, “were two old men with long white beards, dressed in stuff made from the bark of trees, very like the cotton drawers worn in Madagascar. Two of the seven natives had coats of padded nankeen, differing little in shape from those of the Chinese. Others wore long gowns, which were fastened by means of a waist-belt and some little buttons, so that they had no need of drawers. Their heads were bare, but one or two of them wore bearskin bands. They had their forelocks and faces shaven, but the back hair kept about eight or ten inches long, in a different fashion from the Chinese, however, who leave only a round tuft of hair, which they call ‘pen-t-sec.’ All had sealskin boots with the feet artistically worked à la Chinoise.

“Their weapons were bows, spears, and arrows, tipped with iron. The oldest of the natives, to whom the others showed the most respect, had his eyes in a dreadful state; he wore a shade round his head, to protect them from the sun. These natives were grave in manner, and friendly.”

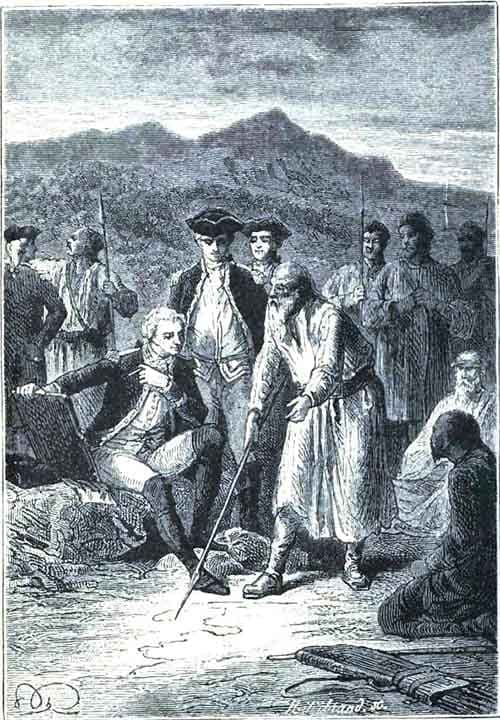

M. de Langle appointed a meeting for the morrow. La Perouse and most of his officers attended. The facts they learned about these Tartars were important, and decided La Perouse to pursue his discoveries further north.

“We succeeded in making them understand,” he says, “that we wished them to draw their country, and that of Manchuria. One of the old men then arose, and with the point of his spear traced the coast of Tartary westward, running nearly N. and S. To the east, vis-à-vis in the same direction, he represented his island, and, placing his hand upon his breast, made us understand that he had indicated his own country. He left an opening between his island and Tartary, and, pointing to our vessels, showed us by signs that they could pass through it. At the south island he delineated another, and left a second opening, indicating that this too was a route for our ships.

“His quickness in understanding us was great, but not equal to that of another islander, about thirty years of age, who, seeing that the figures traced on sand were rubbed out, took one of our pencils and some paper. He traced out his island, which he called Tchoka, and made a line for the little river upon the shore of which we were—placing it two-thirds of the length of the island from north to south. He then drew Manchuria, leaving, as the old man had done, a strait at the extreme end; and to our surprise he added the river Saghalien, the name of which the natives pronounce like ourselves. He placed the mouth of this river a little to the south of the northerly point of his island.

“We afterwards wished to ascertain whether this strait was very wide. We tried to make him understand our idea. He caught at it at once, and, placing his two hands upright at a distance of three inches one from the other, he made us understand that he meant to indicate the width of the little river which formed our watering place; and then, holding them wider apart, he indicated that the second width was to represent that of the river Saghalien; and, separating them still more, he gave the breadth of the strait which divides his country from Tartary.

“M. de Langle and I thought it of the greatest importance to ascertain whether the island we were coasting was that to which geographers had given the name of Saghalien, without guessing its extension southwards. I ordered all hands on board, and prepared to sail in the morning. The bay in which we had anchored received the name of Langle, from the captain who discovered it, and was the first to put foot on land.

“In another bay upon the same shore, called Estaing Bay, the boats landed close to ten or twelve huts. They were larger than those we before had seen, and were divided into two rooms. That at the back contained the stove, cooking utensils, and the bench running all round. That in front was absolutely bare, and probably destined for the reception of strangers. The women fled when they saw the French land. Two of them, however, were caught, and, whilst they were being re-assured, time was found to sketch them. Their faces were peculiar, but pleasant; they had small eyes and thick lips, the upper one being painted or tattooed.”

M. de Langle found the natives gathered about four boats, that were loaded with smoked fish, which they were helping to put in water. They were Manchurians, from the shores of Saghalien River. In the corner of the island was a kind of circus, planted with fifteen or twenty stakes, each surmounted by the head of a bear. It was supposed, not without some show of reason, that these trophies were intended to perpetuate the memory of a victory over this wild beast.

Quantities of cod-fish were obtained upon this coast; and at the mouth of the river a prodigious quantity of salmon was caught. After reconnoitring the bay of La Jonquière, La Perouse cast anchor in Casters Bay. His water supply was nearly exhausted, and he had no more wood. The further he penetrated into the strait which separates Saghalien from the continent, the more the depth diminished. La Perouse, recognizing that he could not double the island of Saghalien by the north, and afraid of not being able to leave the defile in which he now found himself excepting by the strait of Sangaar, which was much further south, determined to remain only five days in Casters Bay, a period which he absolutely needed to take in provisions.

The observatory was set up in a small island, while the carpenters cut down wood, and the sailors filled the water-barrels.

“The huts of these islanders, who call themselves Orotchys,” says the narrative, “are surrounded by a drying ground for salmon, which were exposed to the sun upon perches, after having been smoked for three or four days at the stove which is in the centre of the hut. The women who have charge of this operation take them, as soon as they are smoked through, into the open air, where they become as hard as wood.

“The natives joined us in our fishing with nets or hooks, and we saw them voraciously devouring the head, gills, and sometimes the skin, of raw salmon, tearing it up very cleverly. They sucked out the mucilage, much as we eat oysters. Their fish seldom reach the shore without having first paid toll, unless the catch is very large; and the women show the same eagerness to seize upon the whole fish, and in the same ravenous way devour the mucilaginous parts, which appear to be their tid-bits.

“These people are revoltingly dirty. It would be impossible to find a race farther removed from our ideas of beauty. In height they are less than four foot ten, their bodies are emaciated, their voices are weak and shrill like children’s. They have projecting cheek-bones, bleared and sunken eyes, large mouths, flat noses, short and almost beardless chins, and olive skins, shining with oil and smoke. They allow their hair to grow long, and dress it somewhat in the European style. The women wear it loose over their shoulders, and the description we have given applies to them as well as to the men, from whom they are scarcely to be distinguished, except for a slight difference in their apparel. The women are not subject to any labour, which, as in the case of the American Indians, might have accounted for the inelegance of their appearance. All their time is occupied in cutting out and making their clothes, in drying fish and nursing their children, whom they suckle to the age of three or four years. It rather astonished me to see a child of this age, who had been shooting with bow and arrows, beating a dog, &c., throw himself upon his mother’s bosom, and take the place of an infant of five or six months who was lying asleep upon her knees.”

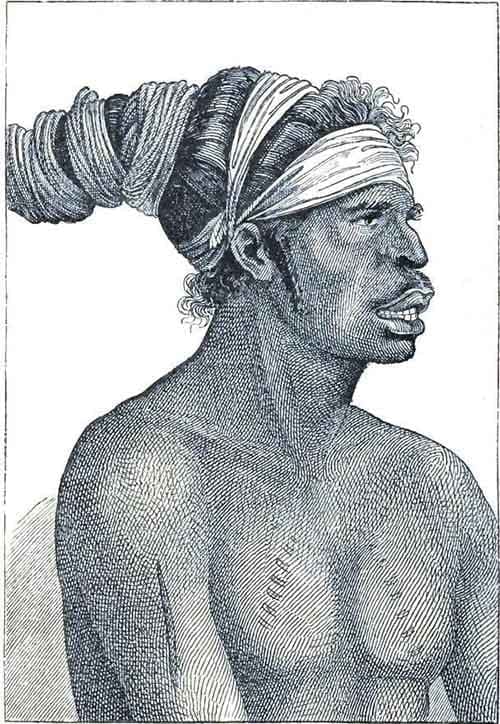

(Fac-simile of early engraving.)

The Bitchys and the Orotchys confirmed much of the information which La Perouse had already obtained. From them he ascertained that the northern point of Saghalien was connected with the continent merely by a sand-bank, on which grew seaweed, and where there was but little water.

This concurrence of testimony left no room for doubt, especially as he never found more than six fathoms in the canal. There remained but one point of interest to determine, and that was the survey of the southern point of Saghalien, which he had only explored as far as Langle Bay in 47° 49′.

Upon the 2nd of August the Astrolabe and the Boussole left Casters Bay, and returned southwards, successively discovering and reconnoitring Monneron Island and Langle Peak, doubling the southern point of Saghalien called Cape Crillon, which led to a strait between Oku-Jesso and Jesso; this they named after La Perouse. Hitherto the geography of this part of the world had been most fanciful and imaginary. Sansen was of opinion that Corea was an island, and that Jesso, Oku-Jesso, and Kamtchatka existed only in imagination; whilst Delisle insisted that Jesso and Oku-Jesso were merely an island, ending at Sangaar Strait; and lastly, Buache, in his “Considérations Géographiques,” page 105, says, “Jesso, after being placed first in the east, then in the south, and finally in the west, was at last found to be in the north.”

To this confusion the discoveries of the French expedition were destined to put an end.

La Perouse had some intercourse with the natives of Crillon Cape, and stated that they were handsome men, far more industrious than the Orotchys of Casters Bay, but less liberal in their dealings.

“They have,” he says, “one most important article of commerce—unknown in the channel of Tartary—from which they derive their riches, namely, whale oil. Of this they collect considerable quantities. They extract it in a way which is far from economical. They cut the flesh into pieces, and dry it upon a slope in the open air, by exposing it to the sun. The oil which flows from it is caught in vessels made of bark, or into bottles of dried sealskin.”

After sighting the Cape Arniva of the Dutch, the vessels coasted along the barren, treeless, uninhabited country in possession of the Dutch Company, and shortly reached the Kurile Islands. They then passed between Marikon Island and the Island of the Four Brothers, calling the strait—the finest amongst the Kurile Islands, through which they penetrated—La Boudeuse.

On the 3rd of September the coast of Kamtchatka was reached. This coast was uninviting enough. “There the eyes rest painfully, and often fearfully, upon enormous masses of rock, which are already covered with snow in the beginning of September, and which never appear to have had any vegetation.”

Three days later Avatscha Bay, or the Bay of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, was reached. The astronomers at once proceeded to take observations; the naturalists made the perilous and arduous ascent of a volcano, some eight leagues inland; whilst those of the crew who were not engaged upon the vessels gave themselves up to hunting and fishing. Thanks to the welcome accorded by the governor, their pleasures were varied.

“We were invited,” says La Perouse, “to a ball which the governor wished to give to all the women, whether from Kamtchatka or Russia. If the ball was not large, it was at least mixed. Thirteen females, clothed in silk, ten of whom were natives of Kamtchatka, with large faces, small eyes, and flat noses, were seated upon benches round the room. Both they and the Russians wore silk handkerchiefs wrapped round the head, in a way similar to those worn by mulattoes. The ball opened with Russian dances, the airs for which were very lively, and like those of the Cossack dances given a short time since in Paris. These were followed by Kamtchatka dances, which were comparable only to the convulsionists of the famous tomb of Saint Médard. The dancers of this part of Asia scarcely require legs, they make such vigorous use of the shoulders and arms. The impression made upon the spectators by the convulsive and contorted movements of the Kamtchatka dancers is painful, and is rendered more so by a pitiful cry which escapes them at intervals, and which is the sole music by which they measure their time. The exertions they made are so formidable that they are completely covered with sweat, and at the conclusion they lie upon the ground unable to move a limb. The exhalations from their bodies permeate the atmosphere with the smell of fish and oil, so strong as to be disagreeable to the unaccustomed nostrils of Europeans.”

The arrival of a courier from Okotsk interrupted the ball. The news he brought was pleasant for every one, but particularly for La Perouse, who learned that he was promoted.

During their stay in this port, the navigators found the tomb of Louis Delisle de la Croyère, Member of the Academy of Sciences, who died in Kamtchatka in 1741, upon his return from an expedition undertaken by command of the Czar for the survey of the American coast. His fellow-countrymen honoured his memory by placing an engraved copper slab over his grave. They paid the same homage to Captain Clerke, Captain Cook’s second in command, and successor.

“Avatscha Bay,” says La Perouse, “is certainly the best, most commodious, and safest to be found in any part of the world. The entrance is narrow, and forts might easily be constructed to command vessels entering it. The anchorage is excellent, the bottom muddy; and two large harbours, one on the eastern shore and one on the west, would hold all the vessels of the French and English navy.”

The Boussole and the Astrolabe set sail upon the 29th of September, 1787. M. de Lesseps, Vice-Consul for Russia, who had accompanied La Perouse thus far upon his expedition, was charged to return to France by land (at that time a most perilous journey), and to convey despatches from the expedition to the government.

The question now arose of finding land discovered in 1620 by the Spaniards. The two frigates passed south of 37° 30′ some three hundred leagues, without finding any trace of it. Crossing the line for the third time, they passed the site given by Byron as that of the Dangerous Islands, without finding them; and, upon the 6th of December, entered the Navigator Archipelago, the merit of discovering which belongs to Bougainville. The vessels were at once surrounded by pirogues. The natives who manned them did not give La Perouse a very favourable idea of the beauty of the inhabitants.

“I saw but two women,” he says, “and they had no delicacy of feature; the younger, who may have been eighteen years of age, had a frightful ulcer upon her leg. Many of these islanders were covered with sores, which may have been the commencement of leprosy; for I noticed two men, whose ulcerated and swollen legs left no doubt as to their malady. They approached us fearlessly and unarmed, and appeared as peaceable as the natives of the Society or Friendly Islands.”

Upon the 9th of December anchor was cast off Maouna Island. Next day the weather was so promising that La Perouse resolved to land to take in water, and then set sail at once, as the anchorage was too bad to admit of a second night’s stay. Every precaution having been taken, La Perouse landed, and proceeded to the spot where his sailors were obtaining water. Captain Langle penetrated to a small creek about a league from the watering place, “and this excursion, from which he returned delighted with the beauty of the village he had seen, was, as will be seen, the cause of our misfortunes.”

Upon the shore, meantime, a brisk trade was going on. Men and women sold hens, parrots, fruits, and pigs. At the same time a native, getting into one of the sloops, possessed himself of a hammer, and commenced dealing vigorous blows upon a sailor’s back. He was speedily seized by four strong fellows, and thrown into the sea.

La Perouse penetrated into the interior, accompanied by women, old men, and children. He enjoyed a delightful excursion through a charming country, which rejoiced in the double advantage of a soil which required no culture, and a climate in which clothing was superfluous.

“Bread-fruits, cocoa-nuts, bananas, guavas, and oranges afforded a wholesome and sufficient nourishment to the inhabitants; while chickens, pigs, and dogs, which lived upon the surplus fruits, afforded the necessary change of diet.

“The first visit passed over without serious danger. There were a few quarrels, it is true; but, thanks to the prudence and reserve of the French, who kept on their guard, they did not amount to anything serious. La Perouse had given orders to re-embark, when M. de Langle insisted upon sending for a few more casks of water.

“He had adopted Captain Cook’s views: he thought fresh water preferable to all other things which he had on board; and as some of his crew showed signs of scurvy, he was right in thinking that every help should be given them.”

La Perouse from the first had a presentiment against consenting. But he yielded when M. de Langle persisted that a captain is responsible for the health of his crew, that the spot which he named was perfectly safe, that he himself would command the expedition, and that three hours would suffice for the work.

“M. de Langle,” says the narrative, “was a man of so much judgment, that his representation influenced my decision more than anything else.

“Next day two boats, under command of M. Boutin and M. Mouton, conveying all the sufferers from scurvy, under charge of six armed soldiers and a captain, in all twenty-eight men, left the Astrolabe, to be under M. de Langle’s orders. M. de Langle was accompanied in his boat by M. de Lauranon and M. Collinet, who were invalids, and M. de Varignas, who was convalescent. M. de Gobien commanded the sloop, M. de la Martinière, M. Lavant, and the elder Receveur, were amongst the thirty-three persons sent by the Boussole. The entire force amounted to sixty-one, and those the picked men of the expedition.

“M. de Langle ordered every one to be armed with guns, and six swivel-guns were placed in the sloop. M. de Langle and all his companions were greatly surprised when, instead of a large and commodious bay, they found a creek filled with coral, which it was only possible to reach through a tortuous channel, where the surf broke violently. M. de Langle had only seen this bay at high tide, and as soon as this new sight met his view his first idea was to regain the former watering-place.

“But the friendly appearance of the natives, the number of women and children he observed among them, the quantities of pigs and fruit they offered for sale, put his prudent resolutions to flight.

“The water-casks of the four boats were landed quietly, the soldiers keeping order upon the shore, and forming a barrier which left a free space for the workers. But this peaceful condition of affairs did not last long. Many of the pirogues, having disposed of their wares to our vessels, returned to the shore, and, landing in the bay of our watering-place, it was soon entirely filled by them. In place of the two hundred natives, counting women and children, whom De Langle had found an hour and a half previously, there were now, at the end of three hours, a thousand or twelve hundred.

“M. de Langle’s situation became more perilous every moment. He succeeded, however, seconded by M. de Varignas, M. Boutin, M. Collier, and Gobien, in embarking the water-casks. But the bay was almost dry, and he could not hope to get his boats off before four o’clock in the afternoon. However, followed by his detachment, he attempted it, and, leading the way with his gun and the soldiers, he forbade firing until he should give the order.

“He felt that he would soon be forced to fire. Already stones were flying; and the Indians who were in shallow water surrounded the sloops for a distance of at least two hundred yards. The soldiers who were already in the boats tried in vain to drive them back.

“M. de Langle was anxious to avoid beginning hostilities, and fearful of being accused of barbarity; otherwise he would, no doubt, have ordered a general discharge, which would effectually have scattered the multitude. But he believed he could subdue the natives without bloodshed, and he was the victim of his humanity.

“Very soon a storm of stones, thrown at short distances with the force of a sling, struck almost all who were in the sloop. M. de Langle had only time to discharge his gun. He was thrown over, and unfortunately fell outside the sloop. He was at once massacred by more than two hundred Indians, who assailed him with clubs and stones. As soon as he expired they fastened him by one arm to the sloop, no doubt with a view to despoiling the body.

“The sloop of La Boussole, under M. Boutin, was run aground within four yards of that of the Astrolabe, and parallel between them was a narrow channel not yet occupied by the Indians. By this outlet, all the wounded who were fortunate enough to avoid falling into the open sea, escaped by swimming. They reached our boats, which fortunately had remained afloat, and we succeeded in saving forty-nine out of the sixty-one men who had composed the expedition.

“M. Boutin had imitated M. de Langle. He would not fire, and only gave orders for a discharge after his commander’s shot. Naturally, at the short distance of four or five paces, every shot killed an Indian; but there was no time to re-load. M. Boutin was knocked down by a stone, and fortunately fell between the two stranded boats. Those who had escaped by swimming towards the two boats had received many wounds, mostly on the head; whilst those who, less fortunate, had fallen overboard upon the side near the Indians, were killed instantaneously.

“The safety of forty-nine of the crew is due to the good order which M. de Varignas was wise enough to maintain, and to the punctuality with which M. Mouton, who commanded the boats of the Boussole, carried out his orders.

“The boat belonging to the Astrolabe was so overloaded that it grounded. The natives at once decided to harass the wounded in their retreat. They hastened in great numbers towards the reefs, within six feet of which the boats must necessarily pass. The little ammunition which remained was exhausted upon these savages, and the boats at last emerged from the creek.”

La Perouse’s first idea was naturally to avenge the death of his unfortunate companions; but M. de Boutin, who, although severely wounded, retained all his faculties, begged him to desist, representing to him that if by any mishap one of the boats ran aground, the creek was so situated, being bordered with trees which afforded secure shelter to the natives, that not a Frenchman would come back alive. La Perouse remained for two days upon the scene of this terrible disaster, without being able to gratify the vindictive desires of his crew.

“No doubt,” says La Perouse, “it will appear incredible that during this time five or six pirogues left the shore, bringing pigs, pigeons, and cocoa-nuts, and offering them in exchange. I was forced to control myself, or I should have disposed of these natives summarily enough.”

It may readily be supposed that an event which deprived La Perouse of a large number of officers, and of thirty-two of his best sailors, was calculated to upset the plans of the expedition. At the slightest approach of danger it would now be necessary to destroy one frigate, in order to arm the other. But one course remained for La Perouse—to set sail for Botany Bay, reconnoitring the various islands he passed, and taking their astronomical positions.

Upon the 14th of December, Oyolava, another island belonging to the same group, and which Bougainville had seen from a distance, was sighted. It was larger than Tahiti, and exceeded that island in beauty, fertility, and in the number of its inhabitants.

The natives resembled those of Maouna in every particular, and quickly surrounded the two frigates, offering the multifarious productions of their island. It appeared that the French must have been the first to trade with them, for they were quite unacquainted with the use or value of iron, and preferred a single coloured bead to a hatchet, or a nail six inches long.

Some of the women had pleasant features and elegant figures; their eyes were gentle, and their movements quiet, whilst the men were wild and fierce in appearance.

Pola Island, also belonging to the Navigator Archipelago, was passed upon the 17th of December. Probably the news of the massacre of the French had already reached this people, for no pirogue approached the vessels.

Cocoa-nut Island and Schouten’s Traitor Island were recognized upon the 20th of December. The latter is divided by a strait, which the navigators would not have perceived, had they not coasted close in shore. About a score of natives appeared, bringing the finest cocoa-nuts La Perouse had ever seen, with a few bananas and one small pig.

These islands, which Wallis calls Boscawen and Keppel Islands, and which he places 1° 13′ too far west, may also be considered part of the Navigator Archipelago. La Perouse considers the natives of this group as belonging to the finest Polynesian race. Tall, vigorous, and well-formed, they are of finer type than those of the Sandwich Islands, whose language is very similar to theirs. Under other circumstances, the captain would have proceeded to explore Oyolava and Pola Islands; but the memory of the disaster at Maouna was too recent, and he dreaded another encounter which might end in massacre.

“Painful associations,” he says, “met us with every succeeding island. In the Recreation Islands, east of the Navigator Archipelago, Roggewein’s crew had been attacked and stoned to death; at Traitor Island, which was now in sight, Schouten’s crew were the victims; and in the south was Maouna Island, where we ourselves had met with so shocking a calamity.

“These recollections affected our way of dealing with the Indians. We now punished every little theft and injustice severely; we demonstrated by force of arms that flight would not save them from our vengeance; we refused to allow them to come on board, and threatened to punish all who did so without permission with death.”

These remarks prove that La Perouse was right in preventing all intercourse between his crews and the natives. We cannot sufficiently praise the prudence and humanity of the commander who, in the excited condition of his men’s minds, knew how to curb the desire for vengeance.

From the Navigator Islands the route was directed to the Friendly Archipelago, which Cook had been unable to explore entirely. Upon the 27th of December, Vavao Island was discovered, one of the largest of the group, which had not been visited by the English navigator. As large as Tonga Tabou, it is higher, and not wanting in fresh water. La Perouse reconnoitred many of these islands, and entered into relations with the natives, who, however, did not offer sufficient provisions to make it worth his while to trade. He therefore resolved upon the 1st of January, 1788, to go to Botany Bay, following a route not yet attempted by any navigator.

Pilstaart Island, discovered by Tasman—or rather, the rock of Pilstaart, for its entire length is but a quarter of a league—presents but a steep and broken appearance, and serves only as a resting-place for sea birds. On this account La Perouse, having no reason for remaining, wished to hasten on to New Holland; but there was another power to be consulted—the wind, and by it La Perouse was detained for three days before Pilstaart.

Norfolk Island and its two islets were sighted upon the 13th of January. La Perouse cast anchor within easy distance of shore, intending to allow the naturalists to land, and inspect the productions of the island; but the waves broke with such violence upon the beach that landing was impossible. Yet Cook had landed there with the greatest facility.

An entire day was passed in vain attempts, and was quite unproductive of scientific results.

Next day La Perouse started afresh, and upon entering the roadstead of Botany Bay encountered an English vessel, under command of Commodore Phillip, who was engaged in constructing Port Jackson, the embryo of that powerful colony which in our day, after only a quarter of a century’s growth, has attained to such a height of civilization and prosperity.

Here the journal kept by La Perouse terminates. A letter, written by him from Botany Bay, upon the 5th of February, to the Naval Minister, informs us that he intended building two sloops, to replace those which had been destroyed at Maouna. All his wounded, amongst them M. Lavaux, the surgeon of the Astrolabe, who had been trepanned, were perfectly recovered. M. de Clenard had assumed command of the Astrolabe, and had been succeeded upon the Boussole by M. de Monti.

In a letter of two days’ later date, giving particulars of his intended route, La Perouse says,—

“I shall regain the Friendly Islands, and carry out the instructions I have received with regard to the northern portion of New Caledonia, to Santa Cruz de Mendana, to the land south of the Arsacides of Surville, and to the Louisiade of Bougainville, and also ascertain, if possible, whether the latter constitutes a portion of New Guinea, or is a separate continent. At the end of July, 1788, I shall pass between New Guinea and New Holland by some other channel than the Endeavour; that is to say, if there be another. During September, and the early part of October, I propose to visit the Gulf of Carpentaria, and the eastern coast of New Holland, as far as Van Diemen’s Land, so as to allow of my return to the north in time to arrive at Mauritius in the beginning of December, 1788.”

Not only did La Perouse fail to keep the rendezvous he himself appointed, but two entire years passed away, and no news whatever of his expedition were received.

Although at that epoch France was passing through a terrible crisis, the interest of the public in the fate of La Perouse was so intense that it found vent in an appeal to the National Assembly from the members of the Society of Natural History in Paris. Upon the 9th of February, 1791, a decree was passed enjoining the fitting out of two or more armed vessels, to be sent in search of La Perouse. It was argued, that had shipwreck overtaken the expedition a number of the crews might still survive, and that it was only just to carry help to them as soon as possible. Men of science, naturalists, and draughtsmen, were to take part in the expedition, with the view to obtaining valuable information for navigation, geography, and commerce, as well as for the arts and sciences. Such were the terms of the decree to which we have alluded.

The command of the expedition was entrusted to Vice-admiral Bruny d’Entrecasteaux, who had attracted the attention of government by his conduct in India. Two vessels, the Recherche, and the Espérance, the latter under the orders of M. Huon de Kermadec, ship’s captain, were placed at his command. The staff of these vessels comprised many officers who later attained to high military positions. Amongst them were, Rossei, Willaumez, Trobriand, La Grandière, Laignel, and Jurien. Amongst the men of science on board were, La Billardière, naturalist, Bertrand and Pierson, astronomers, Ventenat and Riche, naturalists, Beautemps-Beaupré, hydrographer, and Jouveney, engineer.

The vessels were stocked with provisions for eighteen months, and a quantity of merchandise, for trading purposes. Leaving Brest upon the 28th of September, they reached Teneriffe upon the 13th of October. An ascent of the famous Peak followed as a matter of course. La Billardière noticed a phenomenon which had already been observed by him in Asia Minor: his figure was reflected upon the clouds below him, opposite to the sun, in every colour of the rainbow.

Upon the 23rd of October, the necessary provisions having been shipped, anchor was weighed, and the start made for the Cape. During the cruise, La Billardière discovered that the phosphorescent appearance of the sea is caused by minute globular animalculi, floating in the waves. The voyage to the Cape, where the vessels arrived upon the 18th of January, 1792, was barren of incident, if we except the unusual quantity of bonitos, or tunny, and other fish that were met with, and a small leakage which occurred, but was quickly remedied.

At the Cape, D’Entrecasteaux found a letter from M. de Saint Felix, commanding the French forces in India, which seemed likely to upset all his plans, and exercise an unfavourable influence upon the expedition. From this communication it appeared that two French captains, from Batavia, had stated that Commodore Hunter, in command of the English frigate Syrius, had seen, “near the Admiralty Islands, in the Pacific Ocean, men dressed in the European style, and in what he took to be French uniforms.” “It is clear,” wrote M. de Saint Felix, “that the commodore was convinced they were the remnants of La Perouse’s company.”

When D’Entrecasteaux arrived at the Cape, Hunter was still in the roadstead; but within two hours of the arrival of the French vessels he weighed anchor. This conduct, appeared very strange. The commodore had had time to hear that the vessels just arrived were those sent in search of La Perouse, and yet he had made no communication to the commander upon the subject. But it was soon ascertained that Hunter had declared himself quite ignorant of the facts stated by M. de Saint Felix. Were they then to be regarded as unfounded? Incredible as M. de Saint Felix’s communication appeared, D’Entrecasteaux could not suppose so.

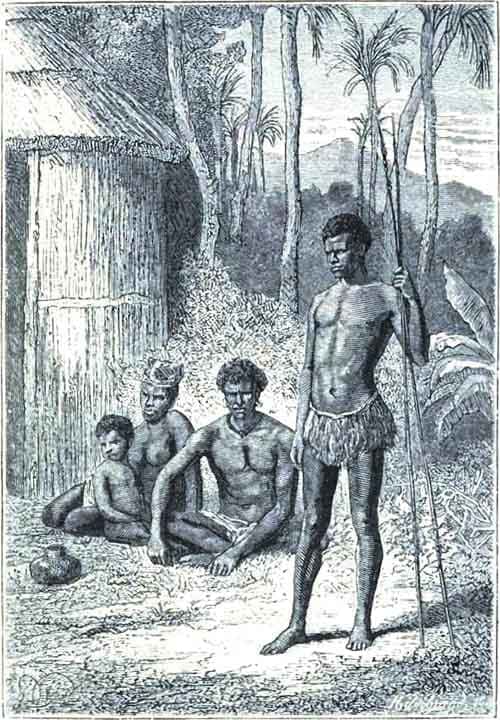

(Fac-simile of early engraving.)

The naturalists had availed themselves of their stay at the Cape to make many excursions in the neighbourhood: La Billardière had penetrated as far into the interior as the short stay of the frigates in the roadstead permitted.