1856.

NARRATIVE.

Charles Dickens having taken an appartement in Paris for the winter months, 49, Avenue des Champs Elysées, was there with his family until the middle of May. He much enjoyed this winter sojourn, meeting many old friends, making new friends, and interchanging hospitalities with the French artistic world. He had also many friends from England to visit him. Mr. Wilkie Collins had an appartement de garçon hard by, and the two companions were constantly together. The Rev. James White and his family also spent their winter at Paris, having taken an appartement at 49, Avenue des Champs Elysées, and the girls of the two families had the same masters, and took their lessons together. After the Whites’ departure, Mr. Macready paid Charles Dickens a visit, occupying the vacant appartement.

During this winter Charles Dickens was, however, constantly backwards and forwards between Paris and London on “Household Words” business, and was also at work on his “Little Dorrit.”

While in Paris he sat for his portrait to the great Ary Scheffer. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy Exhibition of this year, and is now in the National Portrait Gallery.

The summer was again spent at Boulogne, and once more at the Villa des Moulineaux, where he received constant visits from English friends, Mr. Wilkie Collins taking up his quarters for many weeks at a little cottage in the garden; and there the idea of another play, to be acted at Tavistock House, was first started. Many of our letters for this year have reference to this play, and will show the interest which Charles Dickens took in it, and the immense amount of care and pains given by him to the careful carrying out of this favourite amusement.

The Christmas number of “Household Words,” written by Charles Dickens and Mr. Collins, called “The Wreck of the Golden Mary,” was planned by the two friends during this summer holiday.

It was in this year that one of the great wishes of his life was to be realised, the much-coveted house—Gad’s Hill Place—having been purchased by him, and the cheque written on the 14th of March—on a “Friday,” as he writes to his sister-in-law, in the letter of this date. He frequently remarked that all the important, and so far fortunate, events of his life had happened to him on a Friday. So that, contrary to the usual superstition, that day had come to be looked upon by his family as his “lucky” day.

The allusion to the “plainness” of Miss Boyle’s handwriting is good-humouredly ironical; that lady’s writing being by no means famous for its legibility.

The “Anne” mentioned in the letter to his sister-in-law, which follows the one to Miss Boyle, was the faithful servant who had lived with the family so long; and who, having left to be married the previous year, had found it a very difficult matter to recover from her sorrow at this parting. And the “godfather’s present” was for a son of Mr. Edmund Yates.

“The Humble Petition” was written to Mr. Wilkie Collins during that gentleman’s visit to Paris.

The explanation of the remark to Mr. Wills (6th April), that he had paid the money to Mr. Poole, is that Charles Dickens was the trustee through whom the dramatist received his pension.

The letter to the Duke of Devonshire has reference to the peace illuminations after the Crimean war.

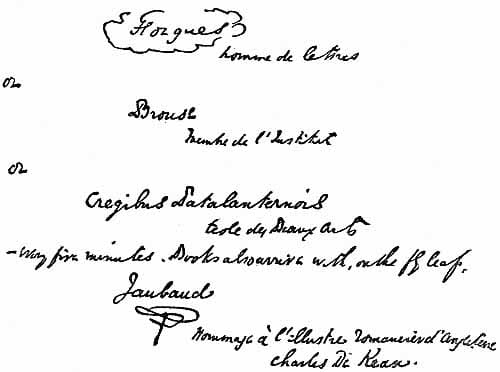

The M. Forgues for whom, at Mr. Collins’s request, he writes a short biography of himself, was the editor of the Revue des Deux Mondes.

The speech at the London Tavern was on behalf of the Artists’ Benevolent Fund.

Miss Kate Macready had sent some clever poems to “Household Words,” with which Charles Dickens had been much pleased. He makes allusion to these, in our two remaining letters to Mr. Macready.

“I did write it for you” (letter to Mrs. Watson, 17th October), refers to that part of “Little Dorrit” which treats of the visit of the Dorrit family to the Great St. Bernard. An expedition which it will be remembered he made himself, in company with Mr. and Mrs. Watson and other friends.

The letter to Mrs. Horne refers to a joke about the name of a friend of this lady’s, who had once been brought by her to Tavistock House. The letter to Mr. Mitton concerns the lighting of the little theatre at Tavistock House.

Our last letter is in answer to one from Mr. Kent, asking him to sit to Mr. John Watkins for his photograph. We should add, however, that he did subsequently give this gentleman some sittings.

Mr. W. H. Wills.

49, Champs Elysées, Sunday, Jan. 6th, 1856.

My dear Wills,

I should like Morley to do a Strike article, and to work into it the greater part of what is here. But I cannot represent myself as holding the opinion that all strikes among this unhappy class of society, who find it so difficult to get a peaceful hearing, are always necessarily wrong, because I don’t think so. To open a discussion of the question by saying that the men are “of course entirely and painfully in the wrong,” surely would be monstrous in any one. Show them to be in the wrong here, but in the name of the eternal heavens show why, upon the merits of this question. Nor can I possibly adopt the representation that these men are wrong because by throwing themselves out of work they throw other people, possibly without their consent. If such a principle had anything in it, there could have been no civil war, no raising by Hampden of a troop of horse, to the detriment of Buckinghamshire agriculture, no self-sacrifice in the political world. And O, good God, when —— treats of the suffering of wife and children, can he suppose that these mistaken men don’t feel it in the depths of their hearts, and don’t honestly and honourably, most devoutly and faithfully believe that for those very children, when they shall have children, they are bearing all these miseries now!

I hear from Mrs. Fillonneau that her husband was obliged to leave town suddenly before he could get your parcel, consequently he has not brought it; and White’s sovereigns—unless you have got them back again—are either lying out of circulation somewhere, or are being spent by somebody else. I will write again on Tuesday. My article is to begin the enclosed.

Ever faithfully.

Mr. Mark Lemon.

49, Champs Elysées, Paris, Monday, Jan. 7th, 1856.

My dear Mark,

I want to know how “Jack and the Beanstalk” goes. I have a notion from a notice—a favourable notice, however—which I saw in Galignani, that Webster has let down the comic business.

In a piece at the Ambigu, called the “Rentrée à Paris,” a mere scene in honour of the return of the troops from the Crimea the other day, there is a novelty which I think it worth letting you know of, as it is easily available, either for a serious or a comic interest—the introduction of a supposed electric telegraph. The scene is the railway terminus at Paris, with the electric telegraph office on the prompt side, and the clerks with their backs to the audience—much more real than if they were, as they infallibly would be, staring about the house—working the needles; and the little bell perpetually ringing. There are assembled to greet the soldiers, all the easily and naturally imagined elements of interest—old veteran fathers, young children, agonised mothers, sisters and brothers, girl lovers—each impatient to know of his or her own object of solicitude. Enter to these a certain marquis, full of sympathy for all, who says: “My friends, I am one of you. My brother has no commission yet. He is a common soldier. I wait for him as well as all brothers and sisters here wait for their brothers. Tell me whom you are expecting.” Then they all tell him. Then he goes into the telegraph-office, and sends a message down the line to know how long the troops will be. Bell rings. Answer handed out on slip of paper. “Delay on the line. Troops will not arrive for a quarter of an hour.” General disappointment. “But we have this brave electric telegraph, my friends,” says the marquis. “Give me your little messages, and I’ll send them off.” General rush round the marquis. Exclamations: “How’s Henri?” “My love to Georges;” “Has Guillaume forgotten Elise?” “Is my son wounded?” “Is my brother promoted?” etc. etc. Marquis composes tumult. Sends message—such a regiment, such a company—”Elise’s love to Georges.” Little bell rings, slip of paper handed out—”Georges in ten minutes will embrace his Elise. Sends her a thousand kisses.” Marquis sends message—such a regiment, such a company—”Is my son wounded?” Little bell rings. Slip of paper handed out—”No. He has not yet upon him those marks of bravery in the glorious service of his country which his dear old father bears” (father being lamed and invalided). Last of all, the widowed mother. Marquis sends message—such a regiment, such a company—”Is my only son safe?” Little bell rings. Slip of paper handed out—”He was first upon the heights of Alma.” General cheer. Bell rings again, another slip of paper handed out. “He was made a sergeant at Inkermann.” Another cheer. Bell rings again, another slip of paper handed out. “He was made colour-sergeant at Sebastopol.” Another cheer. Bell rings again, another slip of paper handed out. “He was the first man who leaped with the French banner on the Malakhoff tower.” Tremendous cheer. Bell rings again, another slip of paper handed out. “But he was struck down there by a musket-ball, and——Troops have proceeded. Will arrive in half a minute after this.” Mother abandons all hope; general commiseration; troops rush in, down a platform; son only wounded, and embraces her.

As I have said, and as you will see, this is available for any purpose. But done with equal distinction and rapidity, it is a tremendous effect, and got by the simplest means in the world. There is nothing in the piece, but it was impossible not to be moved and excited by the telegraph part of it.

I hope you have seen something of Stanny, and have been to pantomimes with him, and have drunk to the absent Dick. I miss you, my dear old boy, at the play, woefully, and miss the walk home, and the partings at the corner of Tavistock Square. And when I go by myself, I come home stewing “Little Dorrit” in my head; and the best part of my play is (or ought to be) in Gordon Street.

I have written to Beaucourt about taking that breezy house—a little improved—for the summer, and I hope you and yours will come there often and stay there long. My present idea, if nothing should arise to unroot me sooner, is to stay here until the middle of May, then plant the family at Boulogne, and come with Catherine and Georgy home for two or three weeks. When I shall next run across I don’t know, but I suppose next month.

We are up to our knees in mud here. Literally in vehement despair, I walked down the avenue outside the Barrière de l’Étoile here yesterday, and went straight on among the trees. I came back with top-boots of mud on. Nothing will cleanse the streets. Numbers of men and women are for ever scooping and sweeping in them, and they are always one lake of yellow mud. All my trousers go to the tailor’s every day, and are ravelled out at the heels every night. Washing is awful.

Tell Mrs. Lemon, with my love, that I have bought her some Eau d’Or, in grateful remembrance of her knowing what it is, and crushing the tyrant of her existence by resolutely refusing to be put down when that monster would have silenced her. You may imagine the loves and messages that are now being poured in upon me by all of them, so I will give none of them; though I am pretending to be very scrupulous about it, and am looking (I have no doubt) as if I were writing them down with the greatest care.

Ever affectionately.

Mr. W. Wilkie Collins.

49, Champs Elysées, Saturday, Jan. 19th, 1856.

My dear Collins,

I had no idea you were so far on with your book, and heartily congratulate you on being within sight of land.

It is excessively pleasant to me to get your letter, as it opens a perspective of theatrical and other lounging evenings, and also of articles in “Household Words.” It will not be the first time that we shall have got on well in Paris, and I hope it will not be by many a time the last.

I purpose coming over, early in February (as soon, in fact, as I shall have knocked out No. 5 of “Little D.”), and therefore we can return in a jovial manner together. As soon as I know my day of coming over, I will write to you again, and (as the merchants—say Charley—would add) “communicate same” to you.

The lodging, en garçon, shall be duly looked up, and I shall of course make a point of finding it close here. There will be no difficulty in that. I will have concluded the treaty before starting for London, and will take it by the month, both because that is the cheapest way, and because desirable places don’t let for shorter terms.

I have been sitting to Scheffer to-day—conceive this, if you please, with No. 5 upon my soul—four hours!! I am so addleheaded and bored, that if you were here, I should propose an instantaneous rush to the Trois Frères. Under existing circumstances I have no consolation.

I think the portrait is the most astounding thing ever beheld upon this globe. It has been shrieked over by the united family as “Oh! the very image!” I went down to the entresol the moment I opened it, and submitted it to the Plorn—then engaged, with a half-franc musket, in capturing a Malakhoff of chairs. He looked at it very hard, and gave it as his opinion that it was Misser Hegg. We suppose him to have confounded the Colonel with Jollins. I met Madame Georges Sand the other day at a dinner got up by Madame Viardot for that great purpose. The human mind cannot conceive any one more astonishingly opposed to all my preconceptions. If I had been shown her in a state of repose, and asked what I thought her to be, I should have said: “The Queen’s monthly nurse.” Au reste, she has nothing of the bas bleu about her, and is very quiet and agreeable.

The way in which mysterious Frenchmen call and want to embrace me, suggests to any one who knows me intimately, such infamous lurking, slinking, getting behind doors, evading, lying—so much mean resort to craven flights, dastard subterfuges, and miserable poltroonery—on my part, that I merely suggest the arrival of cards like this:

—and I then write letters of terrific empressement, with assurances of all sorts of profound considerations, and never by any chance become visible to the naked eye.

At the Porte St. Martin they are doing the “Orestes,” put into French verse by Alexandre Dumas. Really one of the absurdest things I ever saw. The scene of the tomb, with all manner of classical females, in black, grouping themselves on the lid, and on the steps, and on each other, and in every conceivable aspect of obtrusive impossibility, is just like the window of one of those artists in hair, who address the friends of deceased persons. To-morrow week a fête is coming off at the Jardin d’Hîver, next door but one here, which I must certainly go to. The fête of the company of the Folies Nouvelles! The ladies of the company are to keep stalls, and are to sell to Messieurs the Amateurs orange-water and lemonade. Paul le Grand is to promenade among the company, dressed as Pierrot. Kalm, the big-faced comic singer, is to do the like, dressed as a Russian Cossack. The entertainments are to conclude with “La Polka des Bêtes féroces, par la Troupe entière des Folies Nouvelles.” I wish, without invasion of the rights of British subjects, or risk of war, —— could be seized by French troops, brought over, and made to assist.

The appartement has not grown any bigger since you last had the joy of beholding me, and upon my honour and word I live in terror of asking —— to dinner, lest she should not be able to get in at the dining-room door. I think (am not sure) the dining-room would hold her, if she could be once passed in, but I don’t see my way to that. Nevertheless, we manage our own family dinners very snugly there, and have good ones, as I think you will say, every day at half-past five.

I have a notion that we may knock out a series of descriptions for H. W. without much trouble. It is very difficult to get into the Catacombs, but my name is so well known here that I think I may succeed. I find that the guillotine can be got set up in private, like Punch’s show. What do you think of that for an article? I find myself underlining words constantly. It is not my nature. It is mere imbecility after the four hours’ sitting.

All unite in kindest remembrances to you, your mother and brother.

Ever cordially.

Miss Mary Boyle.

49, Champs Elysées, Paris, Jan. 28th, 1856.

My dear Mary,

I am afraid you will think me an abandoned ruffian for not having acknowledged your more than handsome warm-hearted letter before now. But, as usual, I have been so occupied, and so glad to get up from my desk and wallow in the mud (at present about six feet deep here), that pleasure correspondence is just the last thing in the world I have had leisure to take to. Business correspondence with all sorts and conditions of men and women, O my Mary! is one of the dragons I am perpetually fighting; and the more I throw it, the more it stands upon its hind legs, rampant, and throws me.

Yes, on that bright cold morning when I left Peterboro’, I felt that the best thing I could do was to say that word that I would do anything in an honest way to avoid saying, at one blow, and make off. I was so sorry to leave you all! You can scarcely imagine what a chill and blank I felt on that Monday evening at Rockingham. It was so sad to me, and engendered a constraint so melancholy and peculiar, that I doubt if I were ever much more out of sorts in my life. Next morning, when it was light and sparkling out of doors, I felt more at home again. But when I came in from seeing poor dear Watson’s grave, Mrs. Watson asked me to go up in the gallery, which I had last seen in the days of our merry play. We went up, and walked into the very part he had made and was so fond of, and she looked out of one window and I looked out of another, and for the life of me I could not decide in my own heart whether I should console or distress her by going and taking her hand, and saying something of what was naturally in my mind. So I said nothing, and we came out again, and on the whole perhaps it was best; for I have no doubt we understood each other very well without speaking a word.

Sheffield was a tremendous success and an admirable audience. They made me a present of table-cutlery after the reading was over; and I came away by the mail-train within three-quarters of an hour, changing my dress and getting on my wrappers partly in the fly, partly at the inn, partly on the platform. When we got among the Lincolnshire fens it began to snow. That changed to sleet, that changed to rain; the frost was all gone as we neared London, and the mud has all come. At two or three o’clock in the morning I stopped at Peterboro’ again, and thought of you all disconsolately. The lady in the refreshment-room was very hard upon me, harder even than those fair enslavers usually are. She gave me a cup of tea, as if I were a hyena and she my cruel keeper with a strong dislike to me. I mingled my tears with it, and had a petrified bun of enormous antiquity in miserable meekness.

It is clear to me that climates are gradually assimilating over a great part of the world, and that in the most miserable part of our year there is very little to choose between London and Paris, except that London is not so muddy. I have never seen dirtier or worse weather than we have had here since I returned. In desperation I went out to the Barrières last Sunday on a headlong walk, and came back with my very eyebrows smeared with mud. Georgina is usually invisible during the walking time of the day. A turned-up nose may be seen in the midst of splashes, but nothing more.

I am settling to work again, and my horrible restlessness immediately assails me. It belongs to such times. As I was writing the preceding page, it suddenly came into my head that I would get up and go to Calais. I don’t know why; the moment I got there I should want to go somewhere else. But, as my friend the Boots says (see Christmas number “Household Words”): “When you come to think what a game you’ve been up to ever since you was in your own cradle, and what a poor sort of a chap you were, and how it’s always yesterday with you, or else to-morrow, and never to-day, that’s where it is.”

My dear Mary, would you favour me with the name and address of the professor that taught you writing, for I want to improve myself? Many a hand have I seen with many characteristics of beauty in it—some loopy, some dashy, some large, some small, some sloping to the right, some sloping to the left, some not sloping at all; but what I like in your hand, Mary, is its plainness, it is like print. Them as runs may read just as well as if they stood still. I should have thought it was copper-plate if I hadn’t known you. They send all sorts of messages from here, and so do I, with my best regards to Bedgy and pardner and the blessed babbies. When shall we meet again, I wonder, and go somewhere! Ah!

Believe me ever, my dear Mary,

Yours truly and affectionately,

Joe.

(That doesn’t look plain.)

JOE.

Miss Hogarth.

“Household Words,” Friday, Feb. 8th, 1856.

My dear Georgy,

I must write this at railroad speed, for I have been at it all day, and have numbers of letters to cram into the next half-hour. I began the morning in the City, for the Theatrical Fund; went on to Shepherd’s Bush; came back to leave cards for Mr. Baring and Mr. Bates; ran across Piccadilly to Stratton Street, stayed there an hour, and shot off here. I have been in four cabs to-day, at a cost of thirteen shillings. Am going to dine with Mark and Webster at half-past four, and finish the evening at the Adelphi.

The dinner was very successful. Charley was in great force, and floored Peter Cunningham and the Audit Office on a question about some bill transactions with Baring’s. The other guests were B. and E., Shirley Brooks, Forster, and that’s all. The dinner admirable. I never had a better. All the wine I sent down from Tavistock House. Anne waited, and looked well and happy, very much brighter altogether. It gave me great pleasure to see her so improved. Just before dinner I got all the letters from home. They could not have arrived more opportunely.

The godfather’s present looks charming now it is engraved, and John is just now going off to take it to Mrs. Yates. To-morrow Wills and I are going to Gad’s Hill. It will occupy the whole day, and will just leave me time to get home to dress for dinner.

And that’s all that I have to say, except that the first number of “Little Dorrit” has gone to forty thousand, and the other one fast following.

My best love to Catherine, and to Mamey and Katey, and Walter and Harry, and the noble Plorn. I am grieved to hear about his black eye, and fear that I shall find it in the green and purple state on my return.

Ever affectionately.

The Humble Petition of Charles Dickens, a Distressed Foreigner,

Sheweth,

That your Petitioner has not been able to write one word to-day, or to fashion forth the dimmest shade of the faintest ghost of an idea.

That your Petitioner is therefore desirous of being taken out, and is not at all particular where.

That your Petitioner, being imbecile, says no more. But will ever, etc. (whatever that may be).

Paris, March 3rd, 1856.

Mr. Douglas Jerrold.

“Household Words” Office, March 6th, 1856.

My dear Jerrold,

Buckstone has been with me to-day in a state of demi-semi-distraction, by reason of Macready’s dreading his asthma so much as to excuse himself (of necessity, I know) from taking the chair for the fund on the occasion of their next dinner. I have promised to back Buckstone’s entreaty to you to take it; and although I know that you have an objection which you once communicated to me, I still hold (as I did then) that it is a reason for and not against. Pray reconsider the point. Your position in connection with dramatic literature has always suggested to me that there would be a great fitness and grace in your appearing in this post. I am convinced that the public would regard it in that light, and I particularly ask you to reflect that we never can do battle with the Lords, if we will not bestow ourselves to go into places which they have long monopolised. Now pray discuss this matter with yourself once more. If you can come to a favourable conclusion I shall be really delighted, and will of course come from Paris to be by you; if you cannot come to a favourable conclusion I shall be really sorry, though I of course most readily defer to your right to regard such a matter from your own point of view.

Ever faithfully yours.

Miss Hogarth.

“Household Words” Office, Tuesday, March 11th, 1856.

My dear Georgy,

I have been in bed half the day with my cold, which is excessively violent, consequently have to write in a great hurry to save the post.

Tell Catherine that I have the most prodigious, overwhelming, crushing, astounding, blinding, deafening, pulverising, scarifying secret, of which Forster is the hero, imaginable by the whole efforts of the whole British population. It is a thing of that kind that, after I knew it, (from himself) this morning, I lay down flat as if an engine and tender had fallen upon me.

Love to Catherine (not a word of Forster before anyone else), and to Mamey, Katey, Harry, and the noble Plorn. Tell Collins with my kind regards that Forster has just pronounced to me that “Collins is a decidedly clever fellow.” I hope he is a better fellow in health, too.

Ever affectionately.

Miss Hogarth.

“Household Words,” Friday, March 14th, 1856.

My dear Georgy,

I am amazed to hear of the snow (I don’t know why, but it excited John this morning beyond measure); though we have had the same east wind here, and the cold and my cold have both been intense.

Yesterday evening Webster, Mark, Stanny, and I went to the Olympic, where the Wigans ranged us in a row in a gorgeous and immense private box, and where we saw “Still Waters Run Deep.” I laughed (in a conspicuous manner) to that extent at Emery, when he received the dinner-company, that the people were more amused by me than by the piece. I don’t think I ever saw anything meant to be funny that struck me as so extraordinarily droll. I couldn’t get over it at all. After the piece we went round, by Wigan’s invitation, to drink with him. It being positively impossible to get Stanny off the stage, we stood in the wings during the burlesque. Mrs. Wigan seemed really glad to see her old manager, and the company overwhelmed him with embraces. They had nearly all been at the meeting in the morning.

I have seen Charley only twice since I came to London, having regularly been in bed until mid-day. To my amazement, my eye fell upon him at the Adelphi yesterday.

This day I have paid the purchase-money for Gad’s Hill Place. After drawing the cheque, I turned round to give it to Wills (£1,790), and said: “Now isn’t it an extraordinary thing—look at the day—Friday! I have been nearly drawing it half-a-dozen times, when the lawyers have not been ready, and here it comes round upon a Friday, as a matter of course.”

Kiss the noble Plorn a dozen times for me, and tell him I drank his health yesterday, and wished him many happy returns of the day; also that I hope he will not have broken all his toys before I come back.

Ever affectionately.

Mr. W. C. Macready.

49, Champs Elysées, Paris, Saturday, March 22nd, 1856.

My dear Macready,

I want you—you being quite well again, as I trust you are, and resolute to come to Paris—so to arrange your order of march as to let me know beforehand when you will come, and how long you will stay. We owe Scribe and his wife a dinner, and I should like to pay the debt when you are with us. Ary Scheffer too would be delighted to see you again. If I could arrange for a certain day I would secure them. We cannot afford (you and I, I mean) to keep much company, because we shall have to look in at a theatre or so, I daresay!

It would suit my work best, if I could keep myself clear until Monday, the 7th of April. But in case that day should be too late for the beginning of your brief visit with a deference to any other engagements you have in contemplation, then fix an earlier one, and I will make “Little Dorrit” curtsy to it. My recent visit to London and my having only just now come back have thrown me a little behindhand; but I hope to come up with a wet sail in a few days.

You should have seen the ruins of Covent Garden Theatre. I went in the moment I got to London—four days after the fire. Although the audience part and the stage were so tremendously burnt out that there was not a piece of wood half the size of a lucifer-match for the eye to rest on, though nothing whatever remained but bricks and smelted iron lying on a great black desert, the theatre still looked so wonderfully like its old self grown gigantic that I never saw so strange a sight. The wall dividing the front from the stage still remained, and the iron pass-doors stood ajar in an impossible and inaccessible frame. The arches that supported the stage were there, and the arches that supported the pit; and in the centre of the latter lay something like a Titanic grape-vine that a hurricane had pulled up by the roots, twisted, and flung down there; this was the great chandelier. Gye had kept the men’s wardrobe at the top of the house over the great entrance staircase; when the roof fell in it came down bodily, and all that part of the ruins was like an old Babylonic pavement, bright rays tesselating the black ground, sometimes in pieces so large that I could make out the clothes in the “Trovatore.”

I should run on for a couple of hours if I had to describe the spectacle as I saw it, wherefore I will immediately muzzle myself. All here unite in kindest loves to dear Miss Macready, to Katie, Lillie, Benvenuta, my godson, and the noble Johnny. We are charmed to hear such happy accounts of Willy and Ned, and send our loving remembrance to them in the next letters. All Parisian novelties you shall see and hear for yourself.

Ever, my dearest Macready,

Your affectionate Friend.

P.S.—Mr. F.’s aunt sends her defiant respects.

Mr. W. C. Macready.

49, Avenue des Champs Elysées, Paris,

Thursday Night, March 27th, 1856 (after post time).

My dearest Macready,

If I had had any idea of your coming (see how naturally I use the word when I am three hundred miles off!) to London so soon, I would never have written one word about the jump over next week. I am vexed that I did so, but as I did I will not now propose a change in the arrangements, as I know how methodical you tremendously old fellows are. That’s your secret I suspect. That’s the way in which the blood of the Mirabels mounts in your aged veins, even at your time of life.

How charmed I shall be to see you, and we all shall be, I will not attempt to say. On that expected Sunday you will lunch at Amiens but not dine, because we shall wait dinner for you, and you will merely have to tell that driver in the glazed hat to come straight here. When the Whites left I added their little apartment to this little apartment, consequently you shall have a snug bedroom (is it not waiting expressly for you?) overlooking the Champs Elysées. As to the arm-chair in my heart, no man on earth——but, good God! you know all about it.

You will find us in the queerest of little rooms all alone, except that the son of Collins the painter (who writes a good deal in “Household Words”) dines with us every day. Scheffer and Scribe shall be admitted for one evening, because they know how to appreciate you. The Emperor we will not ask unless you expressly wish it; it makes a fuss.

If you have no appointed hotel at Boulogne, go to the Hôtel des Bains, there demand “Marguerite,” and tell her that I commended you to her special care. It is the best house within my experience in France; Marguerite the best housekeeper in the world.

I shall charge at “Little Dorrit” to-morrow with new spirits. The sight of you is good for my boyish eyes, and the thought of you for my dawning mind. Give the enclosed lines a welcome, then send them on to Sherborne.

Ever yours most affectionately and truly.

Mr. W. H. Wills.

49, Champs Elysées, Paris, Sunday, April 6th, 1856.

My dear Wills,

christmas.

Collins and I have a mighty original notion (mine in the beginning) for another play at Tavistock House. I propose opening on Twelfth Night the theatrical season of that great establishment. But now a tremendous question. Is

Mrs. Wills!

game to do a Scotch housekeeper, in a supposed country-house, with Mary, Katey, Georgina, etc.? If she can screw her courage up to saying “Yes,” that country-house opens the piece in a singular way, and that Scotch housekeeper’s part shall flow from the present pen. If she says “No” (but she won’t), no Scotch housekeeper can be. The Tavistock House season of four nights pauses for a reply. Scotch song (new and original) of Scotch housekeeper would pervade the piece.

You

had better pause for breath.

Ever faithfully.

Poole.

I have paid him his money. Here is the proof of life. If you will get me the receipt to sign, the money can go to my account at Coutts’s.

Mrs. Charles Dickens.

Tavistock House, Monday, May 5th, 1856.

My dear Catherine,

I did nothing at Dover (except for “Household Words”), and have not begun “Little Dorrit,” No. 8, yet. But I took twenty-mile walks in the fresh air, and perhaps in the long run did better than if I had been at work. The report concerning Scheffer’s portrait I had from Ward. It is in the best place in the largest room, but I find the general impression of the artists exactly mine. They almost all say that it wants something; that nobody could mistake whom it was meant for, but that it has something disappointing in it, etc. etc. Stanfield likes it better than any of the other painters, I think. His own picture is magnificent. And Frith, in a “Little Child’s Birthday Party,” is quite delightful. There are many interesting pictures. When you see Scheffer, tell him from me that Eastlake, in his speech at the dinner, referred to the portrait as “a contribution from a distinguished man of genius in France, worthy of himself and of his subject.”

I did the maddest thing last night, and am deeply penitent this morning. We stayed at Webster’s till any hour, and they wanted me, at last, to make punch, which couldn’t be done when the jug was brought, because (to Webster’s burning indignation) there was only one lemon in the house. Hereupon I then and there besought the establishment in general to come and drink punch on Thursday night, after the play; on which occasion it will become necessary to furnish fully the table with some cold viands from Fortnum and Mason’s. Mark has looked in since I began this note, to suggest that the great festival may come off at “Household Words” instead. I am inclined to think it a good idea, and that I shall transfer the locality to that business establishment. But I am at present distracted with doubts and torn by remorse.

The school-room and dining-room I have brought into habitable condition and comfortable appearance. Charley and I breakfast at half-past eight, and meet again at dinner when he does not dine in the City, or has no engagement. He looks very well.

The audiences at Gye’s are described to me as absolute marvels of coldness. No signs of emotion can be hammered, out of them. Panizzi sat next me at the Academy dinner, and took it very ill that I disparaged ——. The amateurs here are getting up another pantomime, but quarrel so violently among themselves that I doubt its ever getting on the stage. Webster expounded his scheme for rebuilding the Adelphi to Stanfield and myself last night, and I felt bound to tell him that I thought it wrong from beginning to end. This is all the theatrical news I know.

I write by this post to Georgy. Love to Mamey, Katey, Harry, and the noble Plorn. I should be glad to see him here.

Ever affectionately.

Miss Hogarth.

Tavistock House, Monday, May 5th, 1856.

My dear Georgy,

You will not be much surprised to hear that I have done nothing yet (except for H. W.), and have only just settled down into a corner of the school-room. The extent to which John and I wallowed in dust for four hours yesterday morning, getting things neat and comfortable about us, you may faintly imagine. At four in the afternoon came Stanfield, to whom I no sooner described the notion of the new play, than he immediately upset all my new arrangements by making a proscenium of the chairs, and planning the scenery with walking-sticks. One of the least things he did was getting on the top of the long table, and hanging over the bar in the middle window where that top sash opens, as if he had got a hinge in the middle of his body. He is immensely excited on the subject. Mark had a farce ready for the managerial perusal, but it won’t do.

I went to the Dover theatre on Friday night, which was a miserable spectacle. The pit is boarded over, and it is a drinking and smoking place. It was “for the benefit of Mrs. ——,” and the town had been very extensively placarded with “Don’t forget Friday.” I made out four and ninepence (I am serious) in the house, when I went in. We may have warmed up in the course of the evening to twelve shillings. A Jew played the grand piano; Mrs. —— sang no end of songs (with not a bad voice, poor creature); Mr. —— sang comic songs fearfully, and danced clog hornpipes capitally; and a miserable woman, shivering in a shawl and bonnet, sat in the side-boxes all the evening, nursing Master ——, aged seven months. It was a most forlorn business, and I should have contributed a sovereign to the treasury, if I had known how.

I walked to Deal and back that day, and on the previous day walked over the downs towards Canterbury in a gale of wind. It was better than still weather after all, being wonderfully fresh and free.

If the Plorn were sitting at this school-room window in the corner, he would see more cats in an hour than he ever saw in his life. I never saw so many, I think, as I have seen since yesterday morning.

There is a painful picture of a great deal of merit (Egg has bought it) in the exhibition, painted by the man who did those little interiors of Forster’s. It is called “The Death of Chatterton.” The dead figure is a good deal like Arthur Stone; and I was touched on Saturday to see that tender old file standing before it, crying under his spectacles at the idea of seeing his son dead. It was a very tender manifestation of his gentle old heart.

This sums up my news, which is no news at all. Kiss the Plorn for me, and expound to him that I am always looking forward to meeting him again, among the birds and flowers in the garden on the side of the hill at Boulogne.

Ever affectionately.

The Duke of Devonshire.

Tavistock House, Sunday, June 1st, 1856.

My dear Duke of Devonshire,

Allow me to thank you with all my heart for your kind remembrance of me on Thursday night. My house was already engaged to Miss Coutts’s, and I to—the top of St. Paul’s, where the sight was most wonderful! But seeing that your cards gave me leave to present some person not named, I conferred them on my excellent friend Dr. Elliotson, whom I found with some fireworkless little boys in a desolate condition, and raised to the seventh heaven of happiness. You are so fond of making people happy, that I am sure you approve.

Always your faithful and much obliged.

Mr. W. Wilkie Collins.

Tavistock House, June 6th, 1856.

My dear Collins,

I have never seen anything about myself in print which has much correctness in it—any biographical account of myself I mean. I do not supply such particulars when I am asked for them by editors and compilers, simply because I am asked for them every day. If you want to prime Forgues, you may tell him without fear of anything wrong, that I was born at Portsmouth on the 7th of February, 1812; that my father was in the Navy Pay Office; that I was taken by him to Chatham when I was very young, and lived and was educated there till I was twelve or thirteen, I suppose; that I was then put to a school near London, where (as at other places) I distinguished myself like a brick; that I was put in the office of a solicitor, a friend of my father’s, and didn’t much like it; and after a couple of years (as well as I can remember) applied myself with a celestial or diabolical energy to the study of such things as would qualify me to be a first-rate parliamentary reporter—at that time a calling pursued by many clever men who were young at the Bar; that I made my début in the gallery (at about eighteen, I suppose), engaged on a voluminous publication no longer in existence, called The Mirror of Parliament; that when The Morning Chronicle was purchased by Sir John Easthope and acquired a large circulation, I was engaged there, and that I remained there until I had begun to publish “Pickwick,” when I found myself in a condition to relinquish that part of my labours; that I left the reputation behind me of being the best and most rapid reporter ever known, and that I could do anything in that way under any sort of circumstances, and often did. (I daresay I am at this present writing the best shorthand writer in the world.)

That I began, without any interest or introduction of any kind, to write fugitive pieces for the old “Monthly Magazine,” when I was in the gallery for The Mirror of Parliament; that my faculty for descriptive writing was seized upon the moment I joined The Morning Chronicle, and that I was liberally paid there and handsomely acknowledged, and wrote the greater part of the short descriptive “Sketches by Boz” in that paper; that I had been a writer when I was a mere baby, and always an actor from the same age; that I married the daughter of a writer to the signet in Edinburgh, who was the great friend and assistant of Scott, and who first made Lockhart known to him.

And that here I am.

Finally, if you want any dates of publication of books, tell Wills and he’ll get them for you.

This is the first time I ever set down even these particulars, and, glancing them over, I feel like a wild beast in a caravan describing himself in the keeper’s absence.

Ever faithfully.

P.S.—I made a speech last night at the London Tavern, at the end of which all the company sat holding their napkins to their eyes with one hand, and putting the other into their pockets. A hundred people or so contributed nine hundred pounds then and there.

Mr. Mark Lemon.

Villa des Moulineaux, Boulogne,

Sunday, June 15th 1856.

My dear old Boy,

This place is beautiful—a burst of roses. Your friend Beaucourt (who will not put on his hat), has thinned the trees and greatly improved the garden. Upon my life, I believe there are at least twenty distinct smoking-spots expressly made in it.

And as soon as you can see your day in next month for coming over with Stanny and Webster, will you let them both know? I should not be very much surprised if I were to come over and fetch you, when I know what your day is. Indeed, I don’t see how you could get across properly without me.

There is a fête here to-night in honour of the Imperial baptism, and there will be another to-morrow. The Plorn has put on two bits of ribbon (one pink and one blue), which he calls “companys,” to celebrate the occasion. The fact that the receipts of the fêtes are to be given to the sufferers by the late floods reminds me that you will find at the passport office a tin-box, condescendingly and considerately labelled in English:

For the Overflowings,

which the chief officer clearly believes to mean, for the sufferers from the inundations.

I observe more Mingles in the laundresses’ shops, and one inscription, which looks like the name of a duet or chorus in a playbill, “Here they mingle.”

Will you congratulate Mrs. Lemon, with our loves, on her gallant victory over the recreant cabman?

Walter has turned up, rather brilliant on the whole; and that (with shoals of remembrances and messages which I don’t deliver) is all my present intelligence.

Ever affectionately.

Mr. Mark Lemon.

H. W. Office, July 2nd, 1856.

My dear Mark,

I am concerned to hear that you are ill, that you sit down before fires and shiver, and that you have stated times for doing so, like the demons in the melodramas, and that you mean to take a week to get well in.

Make haste about it, like a dear fellow, and keep up your spirits, because I have made a bargain with Stanny and Webster that they shall come to Boulogne to-morrow week, Thursday the 10th, and stay a week. And you know how much pleasure we shall all miss if you are not among us—at least for some part of the time.

If you find any unusually light appearance in the air at Brighton, it is a distant refraction (I have no doubt) of the gorgeous and shining surface of Tavistock House, now transcendently painted. The theatre partition is put up, and is a work of such terrific solidity, that I suppose it will be dug up, ages hence, from the ruins of London, by that Australian of Macaulay’s who is to be impressed by its ashes. I have wandered through the spectral halls of the Tavistock mansion two nights, with feelings of the profoundest depression. I have breakfasted there, like a criminal in Pentonville (only not so well). It is more like Westminster Abbey by midnight than the lowest-spirited man—say you at present for example—can well imagine.

There has been a wonderful robbery at Folkestone, by the new manager of the Pavilion, who succeeded Giovannini. He had in keeping £16,000 of a foreigner’s, and bolted with it, as he supposed, but in reality with only £1,400 of it. The Frenchman had previously bolted with the whole, which was the property of his mother. With him to England the Frenchman brought a “lady,” who was, all the time and at the same time, endeavouring to steal all the money from him and bolt with it herself. The details are amazing, and all the money (a few pounds excepted) has been got back.

They will be full of sympathy and talk about you when I get home, and I shall tell them that I send their loves beforehand. They are all enclosed. The moment you feel hearty, just write me that word by post. I shall be so delighted to receive it.

Ever, my dear Boy, your affectionate Friend.

Mr. Walter Savage Landor.

Villa des Moulineaux, Boulogne,

Saturday Evening, July 5th, 1856.

My dear Landor,

I write to you so often in my books, and my writing of letters is usually so confined to the numbers that I must write, and in which I have no kind of satisfaction, that I am afraid to think how long it is since we exchanged a direct letter. But talking to your namesake this very day at dinner, it suddenly entered my head that I would come into my room here as soon as dinner should be over, and write, “My dear Landor, how are you?” for the pleasure of having the answer under your own hand. That you do write, and that pretty often, I know beforehand. Else why do I read The Examiner?

We were in Paris from October to May (I perpetually flying between that city and London), and there we found out, by a blessed accident, that your godson was horribly deaf. I immediately consulted the principal physician of the Deaf and Dumb Institution there (one of the best aurists in Europe), and he kept the boy for three months, and took unheard-of pains with him. He is now quite recovered, has done extremely well at school, has brought home a prize in triumph, and will be eligible to “go up” for his India examination soon after next Easter. Having a direct appointment, he will probably be sent out soon after he has passed, and so will fall into that strange life “up the country,” before he well knows he is alive, which indeed seems to be rather an advanced stage of knowledge.

And there in Paris, at the same time, I found Marguerite Power and Little Nelly, living with their mother and a pretty sister, in a very small, neat apartment, and working (as Marguerite told me) hard for a living. All that I saw of them filled me with respect, and revived the tenderest remembrances of Gore House. They are coming to pass two or three weeks here for a country rest, next month. We had many long talks concerning Gore House, and all its bright associations; and I can honestly report that they hold no one in more gentle and affectionate remembrance than you. Marguerite is still handsome, though she had the smallpox two or three years ago, and bears the traces of it here and there, by daylight. Poor little Nelly (the quicker and more observant of the two) shows some little tokens of a broken-off marriage in a face too careworn for her years, but is a very winning and sensible creature.

We are expecting Mary Boyle too, shortly.

I have just been propounding to Forster if it is not a wonderful testimony to the homely force of truth, that one of the most popular books on earth has nothing in it to make anyone laugh or cry? Yet I think, with some confidence, that you never did either over any passage in “Robinson Crusoe.” In particular, I took Friday’s death as one of the least tender and (in the true sense) least sentimental things ever written. It is a book I read very much; and the wonder of its prodigious effect on me and everyone, and the admiration thereof, grows on me the more I observe this curious fact.

Kate and Georgina send you their kindest loves, and smile approvingly on me from the next room, as I bend over my desk. My dear Landor, you see many I daresay, and hear from many I have no doubt, who love you heartily; but we silent people in the distance never forget you. Do not forget us, and let us exchange affection at least.

Ever your Admirer and Friend.

The Duke of Devonshire.

Villa des Moulineaux, near Boulogne,

Saturday Night, July 5th, 1856.

My dear Duke of Devonshire,

From this place where I am writing my way through the summer, in the midst of rosy gardens and sea airs, I cannot forbear writing to tell you with what uncommon pleasure I received your interesting letter, and how sensible I always am of your kindness and generosity. You were always in the mind of my household during your illness; and to have so beautiful, and fresh, and manly an assurance of your recovery from it, under your own hand, is a privilege and delight that I will say no more of.

I am so glad you like Flora. It came into my head one day that we have all had our Floras, and that it was a half-serious, half-ridiculous truth which had never been told. It is a wonderful gratification to me to find that everybody knows her. Indeed, some people seem to think I have done them a personal injury, and that their individual Floras (God knows where they are, or who!) are each and all Little Dorrit’s.

We were all grievously disappointed that you were ill when we played Mr. Collins’s “Lighthouse” at my house. If you had been well, I should have waited upon you with my humble petition that you would come and see it; and if you had come I think you would have cried, which would have charmed me. I hope to produce another play at home next Christmas, and if I can only persuade you to see it from a special arm-chair, and can only make you wretched, my satisfaction will be intense. May I tell you, to beguile a moment, of a little “Tag,” or end of a piece, I saw in Paris this last winter, which struck me as the prettiest I had ever met with? The piece was not a new one, but a revival at the Vaudeville—”Les Mémoires du Diable.” Admirably constructed, very interesting, and extremely well played. The plot is, that a certain M. Robin has come into possession of the papers of a deceased lawyer, and finds some relating to the wrongful withholding of an estate from a certain baroness, and to certain other frauds (involving even the denial of the marriage to the deceased baron, and the tarnishing of his good name) which are so very wicked that he binds them up in a book and labels them “Mémoires du Diable.” Armed with this knowledge he goes down to the desolate old château in the country—part of the wrested-away estate—from which the baroness and her daughter are going to be ejected. He informs the mother that he can right her and restore the property, but must have, as his reward, her daughter’s hand in marriage. She replies: “I cannot promise my daughter to a man of whom I know nothing. The gain would be an unspeakable happiness, but I resolutely decline the bargain.” The daughter, however, has observed all, and she comes forward and says: “Do what you have promised my mother you can do, and I am yours.” Then the piece goes on to its development, in an admirable way, through the unmasking of all the hypocrites. Now, M. Robin, partly through his knowledge of the secret ways of the old château (derived from the lawyer’s papers), and partly through his going to a masquerade as the devil—the better to explode what he knows on the hypocrites—is supposed by the servants at the château really to be the devil. At the opening of the last act he suddenly appears there before the young lady, and she screams, but, recovering and laughing, says: “You are not really the ——?” “Oh dear no!” he replies, “have no connection with him. But these people down here are so frightened and absurd! See this little toy on the table; I open it; here’s a little bell. They have a notion that whenever this bell rings I shall appear. Very ignorant, is it not?” “Very, indeed,” says she. “Well,” says M. Robin, “if you should want me very much to appear, try the bell, if only for a jest. Will you promise?” Yes, she promises, and the play goes on. At last he has righted the baroness completely, and has only to hand her the last document, which proves her marriage and restores her good name. Then he says: “Madame, in the progress of these endeavours I have learnt the happiness of doing good for its own sake. I made a necessary bargain with you; I release you from it. I have done what I undertook to do. I wish you and your amiable daughter all happiness. Adieu! I take my leave.” Bows himself out. People on the stage astonished. Audience astonished—incensed. The daughter is going to cry, when she looks at the box on the table, remembers the bell, runs to it and rings it, and he rushes back and takes her to his heart; upon which we all cry with pleasure, and then laugh heartily.

This looks dreadfully long, and perhaps you know it already. If so, I will endeavour to make amends with Flora in future numbers.

Mrs. Dickens and her sister beg to present their remembrances to your Grace, and their congratulations on your recovery. I saw Paxton now and then when you were ill, and always received from him most encouraging accounts. I don’t know how heavy he is going to be (I mean in the scale), but I begin to think Daniel Lambert must have been in his family.

Ever your Grace’s faithful and obliged.

Mr. W. C. Macready.

Villa des Moulineaux, Boulogne,

Tuesday, July 8th, 1856.

My dearest Macready,

I perfectly agree with you in your appreciation of Katie’s poem, and shall be truly delighted to publish it in “Household Words.” It shall go into the very next number we make up. We are a little in advance (to enable Wills to get a holiday), but as I remember, the next number made up will be published in three weeks.

We are pained indeed to read your reference to my poor boy. God keep him and his father. I trust he is not conscious of much suffering himself. If that be so, it is, in the midst of the distress, a great comfort.

“Little Dorrit” keeps me pretty busy, as you may suppose. The beginning of No. 10—the first line—now lies upon my desk. It would not be easy to increase upon the pains I take with her anyhow.

We are expecting Stanfield on Thursday, and Peter Cunningham and his wife on Monday. I would we were expecting you! This is as pretty and odd a little French country house as could be found anywhere; and the gardens are most beautiful.

In “Household Words,” next week, pray read “The Diary of Anne Rodway” (in two not long parts). It is by Collins, and I think possesses great merit and real pathos.

Being in town the other day, I saw Gye by accident, and told him, when he praised —— to me, that she was a very bad actress. “Well!” said he, “you may say anything, but if anybody else had told me that I should have stared.” Nevertheless, I derived an impression from his manner that she had not been a profitable speculation in respect of money. That very same day Stanfield and I dined alone together at the Garrick, and drank your health. We had had a ride by the river before dinner (of course he would go and look at boats), and had been talking of you. It was this day week, by-the-bye.

I know of nothing of public interest that is new in France, except that I am changing my moustache into a beard. We all send our most tender loves to dearest Miss Macready and all the house. The Hammy boy is particularly anxious to have his love sent to “Misr Creedy.”

Ever, my dearest Macready,

Most affectionately yours.

Mr. W. Wilkie Collins.

Villa des Moulineaux, Boulogne, Sunday, July 13th, 1856.

My dear Collins,

We are all sorry that you are not coming until the middle of next month, but we hope that you will then be able to remain, so that we may all come back together about the 10th of October. I think (recreation allowed, etc.), that the play will take that time to write. The ladies of the dram. pers. are frightfully anxious to get it under way, and to see you locked up in the pavilion; apropos of which noble edifice I have omitted to mention that it is made a more secluded retreat than it used to be, and is greatly improved by the position of the door being changed. It is as snug and as pleasant as possible; and the Genius of Order has made a few little improvements about the house (at the rate of about tenpence apiece), which the Genius of Disorder will, it is hoped, appreciate.

I think I must come over for a small spree, and to fetch you. Suppose I were to come on the 9th or 10th of August to stay three or four days in town, would that do for you? Let me know at the end of this month.

I cannot tell you what a high opinion I have of Anne Rodway. I took “Extracts” out of the title because it conveyed to the many-headed an idea of incompleteness—of something unfinished—and is likely to stall some readers off. I read the first part at the office with strong admiration, and read the second on the railway coming back here, being in town just after you had started on your cruise. My behaviour before my fellow-passengers was weak in the extreme, for I cried as much as you could possibly desire. Apart from the genuine force and beauty of the little narrative, and the admirable personation of the girl’s identity and point of view, it is done with an amount of honest pains and devotion to the work which few men have better reason to appreciate than I, and which no man can have a more profound respect for. I think it excellent, feel a personal pride and pleasure in it which is a delightful sensation, and know no one else who could have done it.

Of myself I have only to report that I have been hard at it with “Little Dorrit,” and am now doing No. 10. This last week I sketched out the notion, characters, and progress of the farce, and sent it off to Mark, who has been ill of an ague. It ought to be very funny. The cat business is too ludicrous to be treated of in so small a sheet of paper, so I must describe it vivâ voce when I come to town. French has been so insufferably conceited since he shot tigerish cat No. 1 (intent on the noble Dick, with green eyes three inches in advance of her head), that I am afraid I shall have to part with him. All the boys likewise (in new clothes and ready for church) are at this instant prone on their stomachs behind bushes, whooshing and crying (after tigerish cat No. 2): “French!” “Here she comes!” “There she goes!” etc. I dare not put my head out of window for fear of being shot (it is as like a coup d’état as possible), and tradesmen coming up the avenue cry plaintively: “Ne tirez pas, Monsieur Fleench; c’est moi—boulanger. Ne tirez pas, mon ami.“

Likewise I shall have to recount to you the secret history of a robbery at the Pavilion at Folkestone, which you will have to write.

Tell Piggot, when you see him, that we shall all be much pleased if he will come at his own convenience while you are here, and stay a few days with us.

I shall have more than one notion of future work to suggest to you while we are beguiling the dreariness of an arctic winter in these parts. May they prosper!

Kind regards from all to the Dramatic Poet of the establishment, and to the D. P.’s mother and brother.

Ever yours.

P.S.—If the “Flying Dutchman” should be done again, pray do go and see it. Webster expressed his opinion to me that it was “a neat piece.” I implore you to go and see a neat piece.

Mr. W. H. Wills.

Boulogne, Thursday, August 7th, 1856.

My dear Wills,

I do not feel disposed to record those two Chancery cases; firstly, because I would rather have no part in engendering in the mind of any human creature, a hopeful confidence in that den of iniquity.

And secondly, because it seems to me that the real philosophy of the facts is altogether missed in the narrative. The wrong which chanced to be set right in these two cases was done, as all such wrong is, mainly because these wicked courts of equity, with all their means of evasion and postponement, give scoundrels confidence in cheating. If justice were cheap, sure, and speedy, few such things could be. It is because it has become (through the vile dealing of those courts and the vermin they have called into existence) a positive precept of experience that a man had better endure a great wrong than go, or suffer himself to be taken, into Chancery, with the dream of setting it right. It is because of this that such nefarious speculations are made.

Therefore I see nothing at all to the credit of Chancery in these cases, but everything to its discredit. And as to owing it to Chancery to bear testimony to its having rendered justice in two such plain matters, I have no debt of the kind upon my conscience.

In haste, ever faithfully.

Mr. W. C. Macready.

Boulogne, Friday, August 8th, 1856.

My dearest Macready,

I like the second little poem very much indeed, and think (as you do) that it is a great advance upon the first. Please to note that I make it a rule to pay for everything that is inserted in “Household Words,” holding it to be a part of my trust to make my fellow-proprietors understand that they have no right to unrequited labour. Therefore, when Wills (who has been ill and is gone for a holiday) does his invariable spiriting gently, don’t make Katey’s case different from Adelaide Procter’s.

I am afraid there is no possibility of my reading Dorsetshirewards. I have made many conditional promises thus: “I am very much occupied; but if I read at all, I will read for your institution in such an order on my list.” Edinburgh, which is No. 1, I have been obliged to put as far off as next Christmas twelvemonth. Bristol stands next. The working men at Preston come next. And so, if I were to go out of the record and read for your people, I should bring such a house about my ears as would shake “Little Dorrit” out of my head.

Being in town last Saturday, I went to see Robson in a burlesque of “Medea.” It is an odd but perfectly true testimony to the extraordinary power of his performance (which is of a very remarkable kind indeed), that it points the badness of ——’s acting in a most singular manner, by bringing out what she might do and does not. The scene with Jason is perfectly terrific; and the manner in which the comic rage and jealousy does not pitch itself over the floor at the stalls is in striking contrast to the manner in which the tragic rage and jealousy does. He has a frantic song and dagger dance, about ten minutes long altogether, which has more passion in it than —— could express in fifty years.

We all unite in kindest love to Miss Macready and all your dear ones; not forgetting my godson, to whom I send his godfather’s particular love twice over. The Hammy boy is so brown that you would scarcely know him.

Ever, my dear Macready, affectionately yours.

Mr. W. H. Wills.

Tavistock House, Sunday Morning, Sept. 28th, 1856.

My dear Wills,

I suddenly remember this morning that in Mr. Curtis’s article, “Health and Education,” I left a line which must come out. It is in effect that the want of healthy training leaves girls in a fit state to be the subjects of mesmerism. I would not on any condition hurt Elliotson’s feelings (as I should deeply) by leaving that depreciatory kind of reference in any page of H. W. He has suffered quite enough without a stab from a friend. So pray, whatever the inconvenience may be in what Bradbury calls “the Friars,” take that passage out. By some extraordinary accident, after observing it, I forgot to do it.

Ever faithfully.

Miss Dickens.

Tavistock House, Saturday, Oct. 4th, 1856.

My dear Mamey,

The preparations for the play are already beginning, and it is christened (this is a great dramatic secret, which I suppose you know already) “The Frozen Deep.”

Tell Katey, with my best love, that if she fail to come back six times as red, hungry, and strong as she was when she went away, I shall give her part to somebody else.

We shall all be very glad to see you both back again; when I say “we” I include the birds (who send their respectful duty) and the Plorn.

Kind regards to all at Brighton.

Ever, my dear Mamey, your affectionate Father.

The Hon. Mrs. Watson.

Tavistock House, Tuesday, Oct. 7th, 1856.

My dear Mrs. Watson,

I did write it for you; and I hoped in writing it, that you would think so. All those remembrances are fresh in my mind, as they often are, and gave me an extraordinary interest in recalling the past. I should have been grievously disappointed if you had not been pleased, for I took aim at you with a most determined intention.

Let me congratulate you most heartily on your handsome Eddy having passed his examination with such credit. I am sure there is a spirit shining out of his eyes, which will do well in that manly and generous pursuit. You will naturally feel his departure very much, and so will he; but I have always observed within my experience, that the men who have left home young have, many long years afterwards, had the tenderest love for it, and for all associated with it. That’s a pleasant thing to think of, as one of the wise and benevolent adjustments in these lives of ours.

I have been so hard at work (and shall be for the next eight or nine months), that sometimes I fancy I have a digestion, or a head, or nerves, or some odd encumbrance of that kind, to which I am altogether unaccustomed, and am obliged to rush at some other object for relief; at present the house is in a state of tremendous excitement, on account of Mr. Collins having nearly finished the new play we are to act at Christmas, which is very interesting and extremely clever. I hope this time you will come and see it. We purpose producing it on Charley’s birthday, Twelfth Night; but we shall probably play four nights altogether—”The Lighthouse” on the last occasion—so that if you could come for the two last nights, you would see both the pieces. I am going to try and do better than ever, and already the school-room is in the hands of carpenters; men from underground habitations in theatres, who look as if they lived entirely upon smoke and gas, meet me at unheard-of hours. Mr. Stanfield is perpetually measuring the boards with a chalked piece of string and an umbrella, and all the elder children are wildly punctual and business-like to attract managerial commendation. If you don’t come, I shall do something antagonistic—try to unwrite No. 11, I think. I should particularly like you to see a new and serious piece so done. Because I don’t think you know, without seeing, how good it is!!!

None of the children suffered, thank God, from the Boulogne risk. The three little boys have gone back to school there, and are all well. Katey came away ill, but it turned out that she had the whooping-cough for the second time. She has been to Brighton, and comes home to-day. I hear great accounts of her, and hope to find her quite well when she arrives presently. I am afraid Mary Boyle has been praising the Boulogne life too highly. Not that I deny, however, our having passed some very pleasant days together, and our having had great pleasure in her visit.

You will object to me dreadfully, I know, with a beard (though not a great one); but if you come and see the play, you will find it necessary there, and will perhaps be more tolerant of the fearful object afterwards. I need not tell you how delighted we should be to see George, if you would come together. Pray tell him so, with my kind regards. I like the notion of Wentworth and his philosophy of all things. I remember a philosophical gravity upon him, a state of suspended opinion as to myself, it struck me, when we last met, in which I thought there was a great deal of oddity and character.

Charley is doing very well at Baring’s, and attracting praise and reward to himself. Within this fortnight there turned up from the West Indies, where he is now a chief justice, an old friend of mine, of my own age, who lived with me in lodgings in the Adelphi, when I was just Charley’s age. He had a great affection for me at that time, and always supposed I was to do some sort of wonders. It was a very pleasant meeting indeed, and he seemed to think it so odd that I shouldn’t be Charley!

This is every atom of no-news that will come out of my head, and I firmly believe it is all I have in it—except that a cobbler at Boulogne, who had the nicest of little dogs, that always sat in his sunny window watching him at work, asked me if I would bring the dog home, as he couldn’t afford to pay the tax for him. The cobbler and the dog being both my particular friends, I complied. The cobbler parted with the dog heart-broken. When the dog got home here, my man, like an idiot as he is, tied him up and then untied him. The moment the gate was open, the dog (on the very day after his arrival) ran out. Next day, Georgy and I saw him lying, all covered with mud, dead, outside the neighbouring church. How am I ever to tell the cobbler? He is too poor to come to England, so I feel that I must lie to him for life, and say that the dog is fat and happy. Mr. Plornish, much affected by this tragedy, said: “I s’pose, pa, I shall meet the cobbler’s dog” (in heaven).

Georgy and Catherine send their best love, and I send mine. Pray write to me again some day, and I can’t be too busy to be happy in the sight of your familiar hand, associated in my mind with so much that I love and honour.

Ever, my dear Mr. Watson, most faithfully yours.

Mrs. Horne.

Tavistock House, Tavistock Square, Oct. 20th, 1856.

My dear Mrs. Horne,

I answer your note by return of post, in order that you may know that the Stereoscopic Nottage has not written to me yet. Of course I will not lose a moment in replying to him when he does address me.

We shall be greatly pleased to see you again. You have been very, very often in our thoughts and on our lips, during this long interval.

And “she” is near you, is she? O I remember her well! And I am still of my old opinion! Passionately devoted to her sex as I am (they are the weakness of my existence), I still consider her a failure. She had some extraordinary christian-name, which I forget. Lashed into verse by my feelings, I am inclined to write:

My heart disowns

Ophelia Jones;

only I think it was a more sounding name.

Are these the tones—

Volumnia Jones?

No. Again it seems doubtful.

God bless her bones,

Petronia Jones!

I think not.

Carve I on stones

Olympia Jones?

Can that be the name? Fond memory favours it more than any other. My love to her.

Ever, my dear Mrs. Horne, very faithfully yours.

The Duke of Devonshire.

Tavistock House, December 1st, 1856.

My dear Duke of Devonshire,

The moment the first bill is printed for the first night of the new play I told you of, I send it to you, in the hope that you will grace it with your presence. There is not one of the old actors whom you will fail to inspire as no one else can; and I hope you will see a little result of a friendly union of the arts, that you may think worth seeing, and that you can see nowhere else.

We propose repeating it on Thursday, the 8th; Monday, the 12th; and Wednesday, the 14th of January. I do not encumber this note with so many bills, and merely mention those nights in case any one of them should be more convenient to you than the first.

But I shall hope for the first, unless you dash me (N. B.—I put Flora into the current number on purpose that this might catch you softened towards me, and at a disadvantage). If there is hope of your coming, I will have the play clearly copied, and will send it to you to read beforehand. With the most grateful remembrances, and the sincerest good wishes for your health and happiness,

I am ever, my dear Duke of Devonshire,

Your faithful and obliged.

Mr. Thomas Mitton.

Tavistock House, Wednesday, Dec. 3rd, 1856.

My dear Mitton,

The inspector from the fire office—surveyor, by-the-bye, they called him—duly came. Wills described him as not very pleasant in his manners. I derived the impression that he was so exceedingly dry, that if he ever takes fire, he must burn out, and can never otherwise be extinguished.

Next day, I received a letter from the secretary, to say that the said surveyor had reported great additional risk from fire, and that the directors, at their meeting next Tuesday, would settle the extra amount of premium to be paid.

Thereupon I thought the matter was becoming complicated, and wrote a common-sense note to the secretary (which I begged might be read to the directors), saying that I was quite prepared to pay any extra premium, but setting forth the plain state of the case. (I did not say that the Lord Chief Justice, the Chief Baron, and half the Bench were coming; though I felt a temptation to make a joke about burning them all.)

Finally, this morning comes up the secretary to me (yesterday having been the great Tuesday), and says that he is requested by the directors to present their compliments, and to say that they could not think of charging for any additional risk at all; feeling convinced that I would place the gas (which they considered to be the only danger) under the charge of one competent man. I then explained to him how carefully and systematically that was all arranged, and we parted with drums beating and colours flying on both sides.

Ever faithfully.

Mr. W. C. Macready

Tavistock House, Saturday Evening, Dec. 13th, 1856.

My dearest Macready,

We shall be charmed to squeeze Willie’s friend in, and it shall be done by some undiscovered power of compression on the second night, Thursday, the 14th. Will you make our compliments to his honour, the Deputy Fiscal, present him with the enclosed bill, and tell him we shall be cordially glad to see him? I hope to entrust him with a special shake of the hand, to be forwarded to our dear boy (if a hoary sage like myself may venture on that expression) by the next mail.

I would have proposed the first night, but that is too full. You may faintly imagine, my venerable friend, the occupation of these also gray hairs, between “Golden Marys,” “Little Dorrits,” “Household Wordses,” four stage-carpenters entirely boarding on the premises, a carpenter’s shop erected in the back garden, size always boiling over on all the lower fires, Stanfield perpetually elevated on planks and splashing himself from head to foot, Telbin requiring impossibilities of smart gasmen, and a legion of prowling nondescripts for ever shrinking in and out. Calm amidst the wreck, your aged friend glides away on the “Dorrit” stream, forgetting the uproar for a stretch of hours, refreshes himself with a ten or twelve miles walk, pitches headforemost into foaming rehearsals, placidly emerges for editorial purposes, smokes over buckets of distemper with Mr. Stanfield aforesaid, again calmly floats upon the “Dorrit” waters.

With very best love to Miss Macready and all the rest,

Ever, my dear Macready, most affectionately yours.

Miss Power.

Tavistock House, December 15th, 1856.

My dear Marguerite,

I am not quite clear about the story; not because it is otherwise than exceedingly pretty, but because I am rather in a difficult position as to stories just now. Besides beginning a long one by Collins with the new year (which will last five or six months), I have, as I always have at this time, a considerable residue of stories written for the Christmas number, not suitable to it, and yet available for the general purposes of “Household Words.” This limits my choice for the moment to stories that have some decided specialties (or a great deal of story) in them.

But I will look over the accumulation before you come, and I hope you will never see your little friend again but in print.

You will find us expecting you on the night of the twenty-fourth, and heartily glad to welcome you. The most terrific preparations are in hand for the play on Twelfth Night. There has been a carpenter’s shop in the garden for six weeks; a painter’s shop in the school-room; a gasfitter’s shop all over the basement; a dressmaker’s shop at the top of the house; a tailor’s shop in my dressing-room. Stanfield has been incessantly on scaffoldings for two months; and your friend has been writing “Little Dorrit,” etc. etc., in corners, like the sultan’s groom, who was turned upside-down by the genie.

Kindest love from all, and from me.

Ever affectionately.

Mr. William Charles Kent.

Tavistock House, Christmas Eve, 1856.

My dear Sir,

I cannot leave your letter unanswered, because I am really anxious that you should understand why I cannot comply with your request.